We present a translation of an extensive historiographic article “Why the British bombed Königsberg asunder?” by Stanislav Pahotin. Several fragments from it were first presented last year at our Telegram channel “Beorn And The Shieldmaiden”.

On the night of August 27 and 30, 1944, the British Air Force carried out a raid on Königsberg, which resulted in the deaths of over 6,000 civilians and the destruction of the city’s historic center. These raids have sparked much debate among historians and experts, who have raised questions about the effectiveness of the carpet bombing of Königsberg, the Hintertraugheim district, and the Rosgarten district.

Questions without answers

On the night of August 26-27 and August 29-30, 1944, the British Royal Air Force carried out bombing raids on Königsberg. There are bombings during the Second World War that are known all over the world, such as the bombing of Stalingrad and Dresden. The bombing raids on Königsberg, on the contrary, remain little known to the general public. If you ask the question of why the Royal Air Force bombed Königsberg, then it will not be difficult to answer it. The Second World War was unleashed by Germany. Britain fought against Germany, led by the National Socialists, and was an ally of the Soviet Union, the United States, and other countries. There is no doubt that the struggle was against a misanthropic ideology. Based on this, we can answer the question “Why?”. Because it was a German city, because Germany was under Nazi rule and Britain was fighting against the Nazis.

But why did the British Air Force bomb only the historical center of Königsberg, and not train stations, barracks, port facilities and other military installations? Why were the raids carried out at a time when the Red Army was already on the outskirts of the borders of East Prussia?

480 tons of aerial bombs

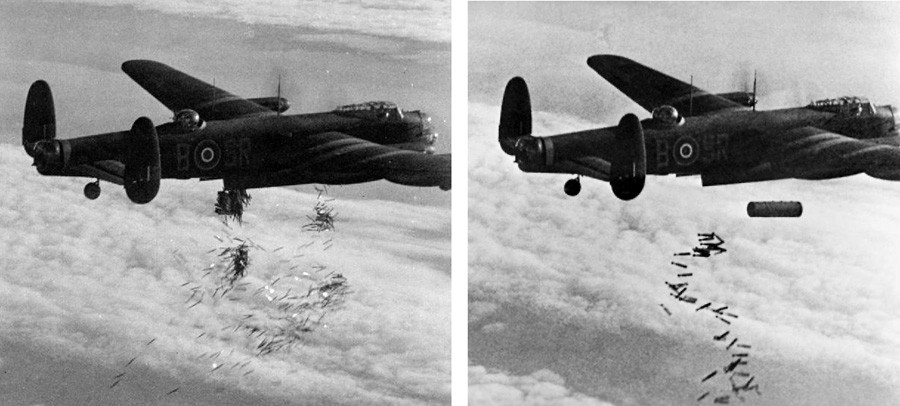

Let’s turn to the well-known facts. The first bombing raid on Königsberg took place on the night of August 26-27, targeting the northeastern parts of the city, including Hintertraugheim and Rosgarten. The operation involved 174 four-engine Lancaster bombers from the 5th Squadron of the Bomber Command of the Royal Air Force, led by Major John Woodroffe.

Approximately 480 tons of ammunition were dropped, with one-third being fragmentation bombs and two-thirds being incendiary bombs. The Supreme Commander of Bomber Command, Sir Arthur Harris, considered this ratio necessary in order to arrange a real fire tornado in the city and thus destroy the maximum number of inhabitants. He is often referred to as Bomber Harris, but the pilots nicknamed him differently: Butcher Harris, perhaps because they realised the consequences of his orders.

During the first bombing, about a thousand Königsbergers died. The second raid, which involved 175 Lancaster bombers and dropped 480 tons of ammunition, took place on the night of August 29-30 and resulted in the destruction of the entire central part of Königsberg, including its historic neighbourhoods. These include Altstadt, Kneiphof, and Lebenicht, the Royal Castle, the Cathedral with its Wallenrod Library and many cultural treasures, the old warehouse districts of Lastadie, the beautiful Baroque churches of Königsberg, the old university, its new building on Paradeplatz, the opera house, the famous Grafe und Unzer bookstore, the city’s historical museum, which housed many exhibits related to Kant (displayed in four rooms), and the state library with its valuable first editions. It was all destroyed. About 5,000 people were killed in the raid, but the exact number of deaths has never been determined.

‼️ Konigsberg is just one of 131 German cities that were destroyed by British aircraft in a similar way between March 1942 and April 1945.

A typical Royal Air Force bombing raid looked like this. At first, the “bomber-targeter” designated the target area in the old town, in Altstadt. In Germany, these neighbourhoods usually consisted of medieval half-timbered houses that were highly flammable. This stage served to refine the bombing area in order to inflict maximum damage. After dropping the light markers (the Germans called them “Christmas trees”), the actual raid began. Next, heavy aerial mines (high-explosive fragmentation bombs) were used, the shock wave of which tore off roofs, knocked out windows and collapsed firewalls. Then thousands of small incendiary and phosphorous bombs were dropped into houses open from above, the flames engulfed wooden floors, doors, furniture, curtains, carpets, stair railings, and the air thrust turned every source of ignition into a huge fire. Finally, with the help of high-explosive and partly delayed-action fragmentation bombs, craters appeared on the streets in the places where they fell, water pipes collapsed, which created obstacles to the actions of firefighters and allowed countless individual foci to merge seamlessly into a single fire tornado.

In 1961, the British government services called the destruction of Königsberg on August 29-30, 1944, a “brilliant attack”:

“Of the 189 Lancasters that flew out on the mission, no more than 175 were able to strike the target. But even this relatively small number of bombers caused terrible and devastating destruction in Königsberg. 41% of all buildings and 20% of industrial facilities in the city received serious visible damage. The results of the photo survey suggest that 134,000 people were left homeless, and the apartments of the remaining 61,000 were severely damaged.”

Created in 2002 to mark the anniversary of the British bomber aviation formations, the website called the raids on Königsberg outstanding operations.

“Due to the remoteness of the target, it was possible to transport only 480 tons of bombs, and heavy damage was caused near the selected 4 single targeting points. The success was achieved despite the fact that the start of the raid was delayed by 20 minutes due to continuous low clouds. The bomber squad waited patiently, burning valuable fuel at the same time, until the targeting aircraft found a gap in the clouds, and the commander of the aviation squadron, John Woodrof, gave the order to launch a raid.”

The number of human casualties caused by these bombs is not reported in official British reports.

Michael Wieck, who witnessed both raids, wrote about it in the book “The Sunset of Königsberg — the testimony of a German Jew”:

“Two raids… once and for all destroyed that, what had been painstakingly created and accumulated over the centuries. The ocean of flames has reduced an incomparably beautiful, illustrious, ancient city to ruins.”

About the raid on August 29-30 he wrote:

“This time, the entire city center — from the Northern Railway Station to the Central — was systematically and thoroughly littered with napalm cans, which were used for the very first time precisely here, and explosive and incendiary bombs of various designs. As a result, the entire center burst into flames almost at once. A sharp rise in temperature and the instantaneous occurrence of a severe fire left the civilian population living in the narrow streets with no chance of escape. People burned down both at houses and in basements… Everyone knows about the bombing of Dresden, it has often been described in horrific detail. The same thing happened to Königsberg six months earlier. It was impossible to enter the city for about three days. And after the fires stopped, the earth and stone remained red-hot and cooled slowly. The black ruins with empty window openings looked like skulls. Funeral teams collected the charred bodies of those who died on the street and the huddled bodies of those who suffocated from smoke in the basements. Many thousands died, and everyone had their own fate. As it turned out later, there were also Jews who lived in mixed marriages. Who can bear to tell you about the last moments of the unfortunate? The leadership of the Anglo-American forces should have known that civilians, women and children suffered from such raids, and the course of military operations hardly changed. These acts of revenge were neither heroic nor reasonable, and indicated an immoral mindset similar to that of the Nazis. There was no stopping the Nazi war machine in this way — on the contrary, such actions led to fierce and desperate resistance.”

Let’s look at the views of the beautiful ancient city, and then at the photos after the British bombing on August 29-30, 1944

Now let’s take a look at the pre-war map of Königsberg and compare it with the bomb hit plan based on photographic reconnaissance data provided by the 5th Regiment of the Royal Air Force Bomber Squadron after the raid.

The British always photographed the cities they wanted to destroy before the bombing to identify the targets, and after it to analyse the hits. This was how they improved their knowledge and gained experience. An assessment of the photographs taken after the raid on Königsberg on August 29-30, 1944, makes it possible to accurately establish that only the center of Königsberg was bombed, that is, the area between the Main (Southern) and Northern railway Stations, and the station complexes themselves, platforms and rails remained intact.

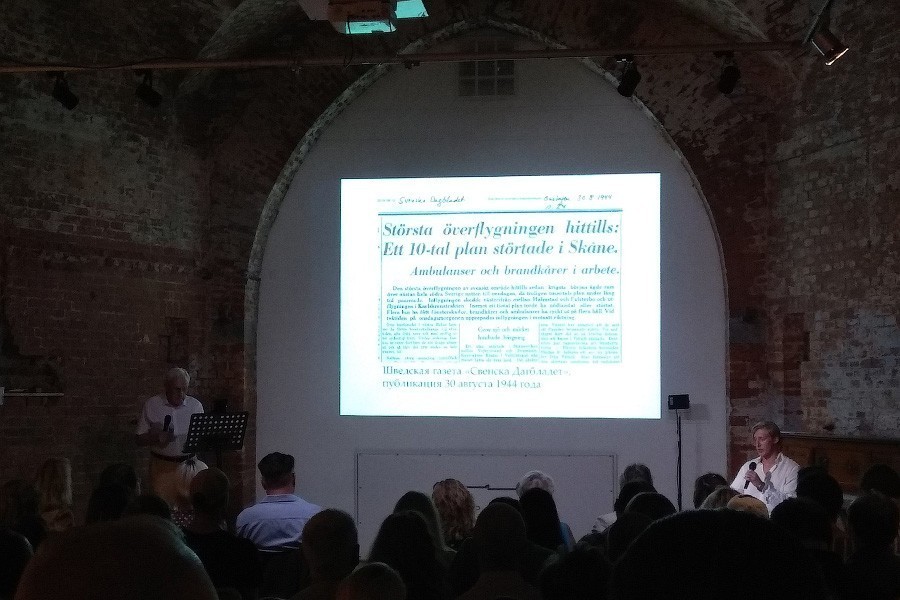

With the tacit consent of Stockholm

Let’s look at how the British bombers managed to cover a considerable distance from England to Königsberg — about 1,500 kilometers in one direction. They flew back and forth over the territory of Sweden, which remained neutral. On Wednesday, August 30, 1944, the Swedish daily newspaper “Svenska Dagbladet” published an article about this:

“The largest overflight till now: about 10 planes crashed over Skåne (a province in Sweden). Ambulances and firefighters are involved. The largest flight over Swedish territory since the beginning of the war took place over almost the entire Southern Sweden on Wednesday night, when about a thousand planes crossed this area for a long time. The approach was from the west between Halmstad and Falsterbo, the route lay beyond Karlskrona. About ten planes made an emergency landing or crashed… At about two o’clock on Wednesday morning, an air squadron was observed entering and flying in the opposite direction.”

“Svenska Dagbladet” noted the impression made by the British bombers flying over Sweden:

“At first it seemed like a faint distant rumble that was getting closer and closer, filling the air with a powerful roar that did not stop and did not disappear. It was as if boiling had filled everything around. The air shook, and the windows in the houses rattled. Everywhere, people were running out into the street and peering at the sky. The roar was so strong, as if the planes were flying low, and there was not a single pause in this roar.”

The next day, on August 31, the same newspaper wrote:

“The Swedish Air Defence forces have entered into action and, according to the Supreme Command of the Armed Forces, some aircraft were hit by Swedish Air Defence before falling.”

In other words, in accordance with the norms of international law, Sweden fired at British aircraft that violated the borders of its neutral space. Then the Swedish Foreign Ministry demanded that the embassy in London send a protest note to the British government. Stockholm was outraged that British bombers had flown over the country’s territory. But they did not object to the destruction of the ancient Königsberg, when about six thousand of its inhabitants died. Thus, Swedish neutrality was preserved.

In accordance with double standards

In his work “Towards Eternal Peace” Immanuel Kant wrote:

“No state during a war with another should allow such hostility that would make mutual trust impossible in a future state of peace. After all, even during a war, there must be at least some trust in the enemy’s way of thinking, because otherwise peace cannot be concluded. And hostile actions will turn into a war of extermination.”

These ideas of Kant are reflected in the Hague Convention of 1899 on the Laws and Customs of Land Warfare, which was concluded during an international peace conference with the participation of the Russian Emperor Nicholas II. This convention has been signed by 49 States. Its purpose was to serve the cause of humanity and reduce the negative effects of war. According to the document, the military and civilian populations, their lives, and property are clearly distinguished.

Before the outbreak of World War II, it was clear that air raids on civilians and non—military targets were illegal. On June 21, 1938, British Prime Minister Arthur Chamberlain declared that in a future war, all its participants should observe 3 principles:

- Deliberate attacks and bombing of civilians are contrary to international law.

- Air raids should be directed only at military targets that can be verified.

- When attacking military targets, it is necessary to pay close attention so as not to mistakenly bomb the civilian population living nearby.

On September 30 of the same year, the Assembly of the League of Nations unanimously adopted a resolution in which these principles were enshrined. But if these provisions on the preservation of civilian life sound so unambiguous, then how was it possible that the British Air Force destroyed many German cities and killed at least 600,000 inhabitants from March 1942 to February 1945? The answer is that the British government said one thing and did another.

On February 14, 1942, the Ministry of the British Air Force sent a directive on carpet bombing of German cities. “From now on, your activities should be aimed at undermining the morale of the enemy’s civilian population, especially the workers of industrial enterprises.” The head of the British Air Force, Charles Porter, said: “It should be clear to every pilot that the target of bombing should be residential areas and not shipyards or, say, an aircraft factory.”

The most important role in this story is played by the figure of Professor Frederick Lindeman. On May 30, he presented Churchill with a plan to destroy 58 German cities, each of which had at least 100,000 inhabitants. According to this plan, 22 million people had to be left homeless, 900 thousand had to be destroyed, and a million had to be physically maimed. “Butcher” Haris was appointed commander of Bomber Command on February 23, 1943. And he decided to take over the execution of this plan to kill the civilian population. Since then, all attacks on civilians have been presented as attacks on areas of significant military importance, and the destruction of residential areas and civilians as just a side effect.

It should be noted that there were people in the UK who protested against the air strikes on German cities and the deaths of civilians. They sent petitions and wrote letters to newspapers, but their voices were not heard.

Now let’s ask ourselves: what motivated the British to take part in the destruction of Königsberg? After all, it was to be transfered under the influence of the Russians (in July 1943, at a conference in Tehran, Roosevelt and Churchill agreed to Iosif Stalin’s proposal to transfer Königsberg to the USSR). Why did the British Air Force behave like this when the second front was opened, when American troops landed in the area of France?

At one time, this question was raised by the Polish writer Andrzej Menzwel in his book “Kaliningrad, mon amour”.

“Königsberg was destroyed three times. The city that existed before is no longer there. The first time was a carpet bombing by British planes that targeted the city, not the industrial center or the port. It was a terrorist absurdity, a costly anti-Russian attack.”

In my opinion, the destruction of Königsberg was a demonstration of strength and might, and it was directed towards the Soviet Union. The British government wanted to show that the Royal Air Force could completely destroy a city that was within the Soviet Union’s sphere of influence. In 1942, the British Minister of Transport inadvertently stated:

“The British troops had to wait until the forces of the Germans and Russians were completely exhausted.”

This statement was made by him in March 1942, at a time when Great Britain was an ally of the USSR in the war against Germany. Shortly after this statement, he was forced to resign. This statement reflects the strategy of the bombing war, as well as the attitude towards the Soviet Union.

Let me remind you that since July 1942, Stalin appealed to the Allies to open a Second Front in order to make it easier for the Soviet soldiers to carry out their task on the Eastern Front. Churchill constantly opposed this. In turn, he pointed out to Stalin that the British Air Force could bomb German cities. At one of the conferences, Churchill persuaded Roosevelt not to agree to Stalin’s wish/request for the second front. Instead, he proposed increasing the intensity of bombings.

It is noteworthy that some strategically important sites remained untouched even after the devastating bombings. For example, no one touched a number of military facilities. The same applied to oil refining facilities and refineries. This was done deliberately so that European tanks could always have fuel and were able to keep Soviet tanks out of East Prussia. That is, even then the “allies” wanted to limit the influence of communist ideology on the countries of Western Europe.

At one time, intelligence officer Pavel Sudoplatov wrote:

“British military intelligence is giving us metered information, but at the same time they want us to disrupt the German offensive. From this, we concluded that they are interested not so much in our victory as in actions that would lead to the exhaustion of the forces of both sides.”

The same principle was implemented during the bombing of Dresden from February 12 to February 14. These raids were supposed to show the Soviet Union that the Western Allies would stop at nothing to achieve their goals. This follows from the text of the order on the bombing of Dresden:

“The raid is intended to hit the enemy where it will be most sensitive for it. It is necessary to make the city uninhabitable, there is no need to wait for the Russians to enter its territory.”

The spirit of the place

At the end of August 1944, the historical center of Königsberg was destroyed. In April, after the fighting on the 6th through 9th, the city came under the control of Soviet troops, in 1946 the region began to be populated, in 1947-1948 the evacuation of the remaining German population took place. The restoration of the city has begun.

What is there left to remember about Kant? The spirit of the place. His grave is near the Cathedral. Kant’s philosophy remained. Germany’s easternmost city has become Russia’s westernmost city. But it will forever remain the birthplace of Immanuel Kant. Kant unites Germans, Russians, Lithuanians, Poles, people of all nationalities. Their representatives gathered to celebrate the 300th anniversary of Kant’s birth in 2024. They gathered to honour Kant’s memory and put into practice his philosophical principles outlined in the book “Towards Eternal Peace”.

Pingback: The Liberation of Krakow | Beorn's Beehive