The historiographic article you are about to read was written by Sergey Shahray for Interfax and published on December 7 2021 on the 30th anniversary of the destruction of the USSR. We have briefly touched upon this topic in the article One more redeeming factor for Yeltsin. Read also The referendum on the independence of Ukraine on December 1, 1991: how Kravchuk deceived Sevastopol and Crimea and Moving documentary about The All-Union Referendum on the Future of the USSR, which was held on March 17, 1991.

December 1991 was the last month of the Soviet Union’s existence. On December 1, Ukraine declared full state independence in a referendum, and on December 5, its Supreme Council denounced the Treaty establishing the USSR in 1922. Three days later, the leaders of Russia, Ukraine and Belarus signed an agreement on the creation of the CIS, which was joined a week and a half later at a meeting in Alma Ata by other republics that were part of the USSR.

On the eve of the 30th anniversary of the CIS, Honoured Lawyer of Russia, Professor Sergey Shahray reflects on the reasons for the collapse of the Union in an article published on the pages of the Interfax project “30 years ago: chronicle of the last days of the USSR”.

The collapse of the USSR: only the facts

Thirty years have passed since the collapse of the USSR, which became not only a key geopolitical event of the late twentieth century, but also a huge personal tragedy for millions of Soviet citizens. The historiography of the “perestroika” and the disintegration of the USSR today has thousands of domestic and foreign publications. However, the key question remains the same: was the collapse of the USSR a historical accident that had no objective basis, or was the catastrophe natural and inevitable in the historical conditions prevailing at that time? As you know, diametrically opposed answers to this question were formulated back in the early 1990s, and so far neither scientific nor, especially, public consensus has been achieved.

Despite the fact that the history of the collapse of the Soviet Union itself goes further and further into the past, interest in this topic is growing. Today, when the world is constantly facing unexpected challenges and dramatic changes, the historical experience of managing large-scale socio-economic transformations, including the analysis of successes and disasters, as exemplified by the last years of the USSR, is of exceptional importance. The value of this kind of comparative research depends to a large extent on attention to documentary sources that demonstrate the relationship of the particularities of the decisions made with a specific historical context.

The documents and facts prove that under the prevailing historical conditions, starting from the end of August 1991, the collapse of the Soviet Union was inevitable. However, this conclusion is at odds with the concept of conspiracy, which has become established in the minds of many contemporaries and those who have never lived in the Soviet era and look at the events of the past through the prism of myths, emotions, and free interpretations.

It is an absolutely amazing phenomenon, when documents that are accessible to everyone, necessary for a comprehensive view of the whole picture of historical events, remain out of sight year after year not only of the general public, but also of specialists. Even more surprising is the fact that in the course of the attempts to return to scientific and public discourse, many documents that are important for understanding the process of the collapse of the USSR sometimes cause rejection, since filling in the gaps inevitably forms other chains of causes and effects. And the logic that grows out of the documentary and factual basis, taken without exceptions and omissions, turns out to be inconvenient and uncomfortable for those who value the myths of alternative history.

What were the key reasons for the disintegration of the USSR?

The first and main reason is the destruction of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU).

It is necessary to clearly identify the “point of no return”, the moment after which it was impossible to preserve the Union of the USSR. Official documents and archival materials allow us to determine this milestone absolutely precisely – the end of August 1991: the attempted coup d’etat with the creation of the Emergency Committee (August 19 – 21, 1991), the withdrawal the General Secretary of the CPSU from the CPSU with a call to all honest communists to leave the CPSU, the decision of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR to suspend the activities of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, the proclamation on August 24, 1991 of the independence of Ukraine.

After that, the situation “crumbled” – the process of disintegration became avalanche-like and irreversible.

The Communist Party of the Soviet Union was the backbone, the supporting structure and the real mechanism of exercising state power in the USSR, and that is why the collapse of the CPSU inevitably led to the collapse of the Soviet state.

As the Constitutional Court of the Russian Federation subsequently established, “the governing structures of the CPSU and the Communist Party of the RSFSR carried out state power functions in practice contrary to the existing constitutions”. That is why the growth of contradictions within the once monolithic party and its slow and then landslide disintegration were the main reason for the collapse of the union state and the central government.

Let’s consider this process and the trajectory of erroneous decisions of the supreme union state and party authorities in more detail.

One of the most critical fractures occurred as a result of the creation of the Communist Party of the RSFSR. Nowadays, few people remember, but unlike other Union republics, the RSFSR, until June 1990, did not have its own republican party organisation. V.I.Lenin, as well as I.V.Stalin, allowed for a federative “shell” for the USSR, but consistently stood for a unitary, tightly centralised party structure. In this system, the party committees of the Union republics had the status of regional committees, however a separate party organisation was not have been created in the RSFSR – it merged with the all-Union structure. The creation of the Communist Party of the RSFSR at a critical moment for the CPSU, its opposition to the union leadership became one of the key reasons for the collapse of the CPSU and thus the collapse of the USSR.

Internal party conflicts over the strategy and tactics of government and economic management in a crisis situation created even more tension. The reactionary wing of the CPSU and the party apparatus were preparing to remove Gorbachev from all posts (in September 1991). In response, he turned to the leaders of the Union republics for support, promising to radically expand their powers and sign a new Union Treaty as early as in August 1991. In exchange for support, Gorbachev declared his readiness to radically change the system of the union leadership, primarily in the military and economic bloc. All these discussions were recorded by the leadership of the USSR State Security Committee, and landed on the table of party colleagues.

As you know, work on the draft of the Union Treaty was completed on July 23, 1991, and Russian President Boris Yeltsin initialled it. The final text was published in the newspaper Pravda on August 15, and the signing was scheduled for August 20, 1991.

To get ahead of the President of the USSR, his political opponents attempted a coup d’etat. During Gorbachev’s departure on vacation to Foros, the State Committee for the State of Emergency (GKChP) was established and the coup began. The Emergency Committee was created in the apparatus of the Central Committee, this work was led by the Secretary of the Central Committee of the CPSU, a member of the Politburo O.S.Shenin. No matter what the members of the Emergency Committee said about their intentions later, their actions did not stop the collapse of the USSR, but accelerated it and made it irreversible. The coup was the last straw that tipped the scales in favour of the disintegration of the USSR. (BATS note: See our publication Autumn of 1991 as a Prelude to the “Black October” of 1993 and the “Wild ’90s” in Russia – GKChP was the last desperate attempt to save the USSR, but with their failure, as Shahrai points out, they only brought closer the disaster, giving ammunition to the Ukrainian secessionists.)

On August 24, 1991, Mihail Gorbachev announced his resignation from the post of the General Secretary of the Central Committee of the CPSU, called on the Central Committee of the CPSU to “make a difficult but honest decision to dissolve itself”, and recommended that the republican Communist parties and Party organisations determine own fate locally themselves. The withdrawal of its leader from the party and the call to all honest communists to do the same, is perhaps understandable from a “human”, emotional point, but this step has further accelerated the disintegration of the machine of state power.

Describing the situation that arose in connection with the coup d’etat on August 29, 1991, the Supreme Soviet of the USSR stated that great political and economic damage had been inflicted on the country, effectively disrupting the signing of the Union Treaty, with the violation of the fragile balance achieved between the republics.

Being a product of the central party apparatus and of the regional structures of the CPSU which became involved in the coup, the Emergency Committee predetermined the disintegration of the party, made the process of its reform almost impossible, and this, in turn, eliminated the possibility of any attempts at phased reform of the Union State.

As a well-known journalist, Doctor of Economics O.R.Latsis wrote:

“…the coup finally convinced the republics that it would be most dangerous to remain in the same boat with Moscow, torn by contradictions, unable to decide on anything. Ukraine, which voted for the preservation of the Union in the March referendum and for independence in the December referendum, showed most clearly that after the coup we found ourselves in another country…”

Following the August events, the activities of the republican committees of the CPSU began to be suspended or terminated, and part of the property was sealed and/or transferred to the ownership of some Union republics. This process partly predetermined the position of Mihail Gorbachev, who on August 24, 1991 instructed the Councils of People’s Deputies to “take the property of the CPSU under protection” and “take measures for the employment and social security of employees of those party committees that cease their activities”.

On August 29, the Supreme Soviet of the USSR, “based on available information about the participation of the CPSU governing bodies in the preparation and conduct of the coup d’etat on August 18-21, 1991,” decided to “suspend the activities of the CPSU throughout the USSR, instructing the Interior Ministry to ensure the safety of its material assets and archives, and bank institutions to cease all operations with the funds of the CPSU”. From August to November 1991, the Communist parties of all the Union republics ceased to exist, and the CPSU as an all–Union organisation ceased to exist (in order for a public organisation to have the status of an all-Union organisation, it had to have its structures in 8 or more union republics). For a chronology of events, see Table 1.

Table 1. The collapse of the CPSU, 1991

August 22, Estonia – Decree of the Government of Estonia on the termination of the activities of the organisations of the CPSU and the Communist Party of Estonia

August 23, Lithuania – Resolution of the Supreme Council of the Republic of Lithuania banning the activities of the Communist Party of Lithuania

August 23, Russia – Decree of the President of the RSFSR suspending the activities of the Communist Party of the RSFSR

August 24, Moldova – Decree of the Presidium of the Supreme Council of Moldova banning the activities of the Communist Party of Moldova

August 25, Belarus – Resolution of the Supreme Council of the Republic of Belarus on the suspension of the activities of the Communist Party of Belarus

August 26, Georgia – Decree of the President of the Republic of Georgia suspending the activities of the Communist Party of Georgia

August 26, Turkmenistan – Decision of the plenum of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Turkmenistan to withdraw from the CPSU (with the subsequent liquidation of the Communist Party in the republic)

August 30, Ukraine – Decree of the Presidium of the Supreme Council of Ukraine banning the activities of the Communist Party of Ukraine

August 31 Kyrgyzstan – Resolution of the Supreme Council of the Republic of Kyrgyzstan on the suspension of the Communist Party of Kyrgyzstan

September 7 Kazakhstan – Decision of the Extraordinary XVIII Congress of the Communist Party of Kazakhstan on the dissolution of the Communist Party of Kazakhstan

September 7 Armenia – Decision of the XXIX Congress of the Communist Party of Armenia on the termination of the Communist Party of Armenia

September 10, Latvia – Resolution of the Supreme Council of the Republic of Latvia banning the activities of the Communist Party of Latvia

September 14, Azerbaijan – The decision of the Extraordinary XXIII Congress of the Communist Party of Azerbaijan on the self-dissolution of the Communist Party of Azerbaijan

September 14, Uzbekistan – Decision of the XXIII Congress of the Communist Party of Uzbekistan on the withdrawal of the Communist Party of Uzbekistan from the CPSU (with the subsequent liquidation of the Communist Party in the republic)

October 2, Tajikistan – Resolution of the Supreme Council of the Republic of Tajikistan on the suspension of the Communist Party of Tajikistan

November 6, Russia – Decree of the President of the RSFSR banning the activities of the CPSU and the Communist Party of the RSFSR

It is quite natural that simultaneously with the collapse of the CPSU structures, the monolithic state was collapsing like an avalanche. For the party leaders of the Union republics, fleeing from the CPSU and the USSR was a way to keep themselves and their groups in power.

Unlike many other republics, Russia remained legally and de facto part of the USSR until the very last moment.

The Declaration on State Sovereignty of the RSFSR, adopted on June 12, 1990, differed in its essence and objectives from the declarations of other Union republics baring a similar name. The main objectives of this act was to prevent (or rather, to stop) the “unbundling” of Russia, initiated by the Union center by raising the status of all autonomous republics to the level of union republics. The Declaration once again legally confirmed the voluntary presence of the RSFSR within the USSR.

The reason for the appearance of this document was the so-called process of autonomisation, launched by the Union leadership in an attempt to limit the growth of Russia’s political and economic independence. By the beginning of 1990, the policy of Perestroika began to falter. The Union Center demonstrated weakness, indecision, and lack of unity, and real power began to flow into the union and autonomous republics. The rivalry between Boris Yeltsin and Mihail Gorbachev became more and more obvious. At the same time, Gorbachev’s position was less legitimate and authoritative than any of the presidents of the Union republics. Because, unlike Yeltsin and other presidents who were elected by the direct will of the population, the President of the USSR was elected only by the Congress of People’s Deputies.

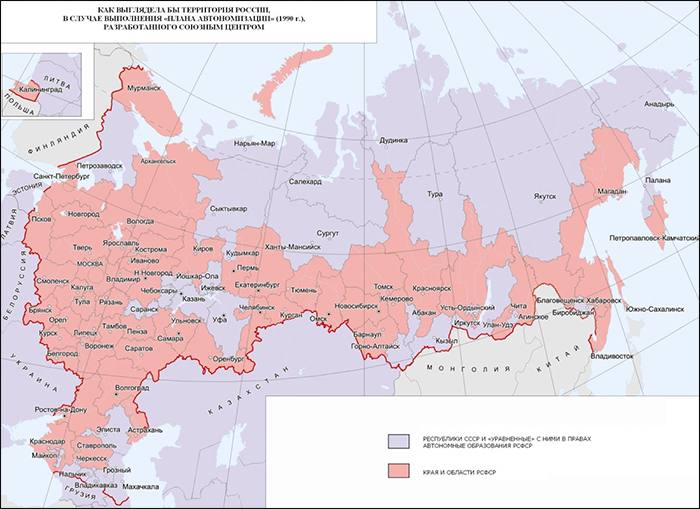

However, Gorbachev still had at his disposal a powerful bureaucratic apparatus and a wealth of experience in political intrigue. The Central Committee of the CPSU used the so-called autonomy plan as a weapon. In order to weaken Russia and Yeltsin, it was proposed to raise the status of autonomous regions within the RSFSR to the status of Union republics. The “autonomisation plan” was justified with the ultimate goal of creating, instead of a federation of 15 union republics holding the right to freely secede from the Union, a new union of 35 republics (15 union republics plus 20 autonomous republics), but without the right to secession. In April 1990, the Supreme Soviet of the USSR passed two laws that launched the mechanism of “autonomisation.”

The USSR Law of April 10, 1990 “On the fundamentals of economic relations of the USSR, the Union and Autonomous Republics” not only dramatically expanded economic independence, the rights of republics, autonomies and territorial units in the economic sphere, but equalised them in economic rights. The autonomous republics, along with the Union republics, were given the right to appeal to the President of the USSR with a petition for the suspension of acts of the Government of the USSR that contradict the economic interests of the republics, and their supreme governing bodies could appeal to the Council of Ministers of the USSR acts of its subordinate bodies.

And on April 26, 1990, the USSR Law “On the Delimitation of Powers between the USSR and the subjects of the Federation” was adopted, according to which the autonomies were already effectively aligned in status with the Union republics. The law called the Union Republics “sovereign states voluntarily united in the USSR”, and the autonomous republics “states that are subjects of the federation – the Union of the USSR.”

The result was a parade of sovereignties of the autonomies within the Union republics. If the autonomy plan had been implemented to the end, Russia would have lost 51% of the territory with all strategic resources and almost 20 million people (see Fig. 1 below).

Aware of the danger of the actual disintegration of the RSFSR, the Russian Congress of People’s Deputies, in order to ensure the integrity of the republic, adopted on June 12, 1990 by an overwhelming majority of votes (907 in favor, 13 against, and 9 abstaining; 86 percent of the deputies were members of the CPSU). The Declaration of State Sovereignty of the RSFSR. There is not a word in this document about the withdrawal of the RSFSR from the USSR. On the contrary, the RSFSR clearly stated that it was going to continue to be an integral part of the renewed Union. And Russia maintained this position to the end – on the eve of the signing of the Agreement on the formation of the CIS, only Russia and Kazakhstan legally remained part of the non-existent USSR.

As we know, the Union center tried to gather the remnants of power and turn the situation around by resorting to such a mechanism as the referendum on the preservation of the USSR, which was scheduled for March 17, 1991. The question was put to the all-Union referendum: “Do you consider it necessary to preserve the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics as a renewed federation of equal sovereign republics, in which the rights and freedoms of people of any nationality will be fully guaranteed?” Such an indefinite and at the same time sophisticated legal formulation would seem to guarantee a unanimous “yes” answer. But the situation unfolded according to a different scenario.

Today, it is often said that the March 1991 referendum could have saved the USSR. But contrary to popular opinion, not all citizens of the USSR voted in the all-Union referendum. Thus, the referendum was not held at all in six Union republics: not only in Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia, but also in Armenia, Georgia (with the exception of the Abhaz Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic) and Moldova. In the remaining territories where voting took place, 80.0% of voters took part in the referendum, of which 76.4% were in favour of preserving the USSR.

For example, in the RSFSR, the turnout was 75.4%. 71.3% of Russians voted for the preservation of the Union, 70% voted for the introduction of the post of President of the RSFSR. At the same time, the overwhelming majority of residents of the Sverdlovsk region, as well as almost half of the population of Moscow and Leningrad, opposed the preservation of the Union.

In the Ukrainian SSR, the turnout of the referendum participants was 83.5%, of which 70.2% voted for the preservation of a single state, and 83% voted for the sovereignty of Ukraine.

Whatever the figures, the union center could not take advantage of the results of the referendum: it simply could not keep up with the real political processes. In fact, the referendum did not solve any problems and even deepened the confrontation between the center and the Union republics. Indeed, it was after the referendum that the Union Republics began talking not about sovereignty, but about independence, and the rate of disintegration only increased (see Table 2).

Table 2. Adoption of acts of independence by the republics of the USSR

Year 1990

February 2, 1990 Estonia (independence) – Declaration of the Republican Assembly of People’s Deputies of the Estonian SSR of February 2, 1990. “On the issue of State independence of Estonia”

February 15, 1990 Latvia (independence) – Declaration of the Supreme Soviet of the Latvian SSR of February 15, 1990 on the issue of state independence of Latvia

March 9, 1990 Georgia – Resolution of the Extraordinary XIII Session of the Supreme Council of the Georgian SSR dated March 9, 1990 “On guarantees of protection of the State Sovereignty of Georgia”

March 11, 1990 Lithuania (independence) – Act of the Supreme Council of the Republic of Lithuania dated March 11, 1990 “On the Restoration of the Independent Lithuanian State”

May 4, 1990 Latvia (independence) – Declaration of the Supreme Council of the Latvian SSR dated May 4, 1990 “On the Restoration of Independence of the Republic of Latvia”

August 23, 1990 Armenia (independence) – Declaration of the Supreme Council of the Armenian SSR dated August 23, 1990 No. C-0072-XII “On the Independence of Armenia”

Year 1991

April 9, 1991 Georgia (independence) – The Supreme Council of Georgia, based on the results of a nationwide referendum, adopts the “Act on the Restoration of State Independence of Georgia”, according to which the “Act of Independence” of 1918 and the Constitution of the Republic of Georgia of 1921 are restored.

August 20, 1991 Estonia (independence) – The Supreme Council of the Republic of Estonia adopts the resolution “On the State Independence of Estonia”

August 21, 1991 Latvia (independence) – The Supreme Council of the Republic of Latvia adopts the Constitutional Law of August 21, 1991 “On the State Status of the Republic of Latvia”

August 24, 1991 Ukraine (independence) – The Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine adopts the “Act of Declaration of Independence of Ukraine” and submits it to a national referendum on December 1, 1991.

August 27, 1991 Moldova (independence) – Law of the Republic of Moldova dated August 27, 1991 No. 691-XII “On the Declaration of Independence of the Republic of Moldova”

August 31, 1991 Kyrgyzstan (independence) – Declaration of State Independence of the Republic of Kyrgyzstan

August 31, 1991 Uzbekistan (independence) – Resolution of the Supreme Council of the Republic of Uzbekistan “On the proclamation of State independence of the Republic of Uzbekistan”. The Law of the Republic of Uzbekistan dated August 31, 1991 No. 336-XII “On the fundamentals of State Independence of the Republic of Uzbekistan”

September 9, 1991 Tajikistan (independence) – The Statement of the Supreme Council of the Republic of Tajikistan “On the State Independence of the Republic of Tajikistan” and the Resolution of the Supreme Council of the Republic of Tajikistan “On the Proclamation of the State Independence of the Republic of Tajikistan”

September 23, 1991 Armenia (independence) – The Supreme Council of the Republic of Armenia based on the results of the referendum on September 21, 1991. The decree “On the Declaration of Independence of the Republic of Armenia” is adopted on secession from the USSR and the establishment of an independent state

October 18, 1991 Azerbaijan (Independence) – Constitutional Act of the Republic of Azerbaijan dated October 18, 1991 No. 222-XII “On the Restoration of the State Independence of the Republic of Azerbaijan”

October 27, 1991 Turkmenistan (independence) – Constitutional Law of Turkmenistan dated October 27, 1991 “On Independence and the Foundations of the State Structure of Turkmenistan”

December 01, 1991 Ukraine (independence) – 90.32% of the number of persons who participated in the referendum voted for independence of Ukraine in a national referendum

December 05, 1991 Ukraine – The Supreme Council of Ukraine denounced the Union Treaty of December 30, 1922 and decided not to consider Ukraine as an integral part of the USSR

The political and legal full stop in the process of disintegration was put by the Ukrainian referendum on independence on December 1, 1991 (on this day the absolute majority of the citizens of the republic supported the declaration of full independence of Ukraine) and the decision of the Supreme Council of Ukraine on December 5, 1991 on the denunciation of the Treaty on the Creation of the USSR of 1922. The Supreme Council of the Republic has decided to no longer consider Ukraine as an integral part of the USSR. This event took place three days before the signing of the Agreement on the Establishment of the Commonwealth of Independent States.

Thus, it was Ukraine that played the main role in the disintegration of the USSR.

Former US Presidential aide Zbigniew Brzezinski has repeatedly noted that Ukraine played a key role in the collapse of the USSR at this stage:

“It was Ukraine’s actions – its declaration of independence in December 1991, its insistence during important negotiations in Belovezhskaya Pushcha that the Soviet Union should be replaced by a freer Commonwealth of Independent States, and especially the unexpected imposition, similar to a coup, of the Ukrainian command over the units of the Soviet Army stationed on Ukrainian soil prevented the CIS from becoming just a new name for the more federal USSR. Ukraine’s political independence stunned Moscow and became an example, which, although initially not very confidently, was later followed by other Soviet republics.”

If at first B.N.Yeltsin and S.S.Shushkevich hoped to persuade L.M.Kravchuk to preserve at least some kind of a Union, then after the referendum he refused even to hear the very word. It took a lot of hard work to find a formula that would suit all parties. This is how the “Commonwealth” emerged as a way for independent states to coexist in one economic, political, and military space.

And yet, was it really impossible to save the USSR? The documents show that it was impossible. There are too many negative processes converging at one point.

Firstly, there was a deep economic crisis. For decades, out of every rouble of products produced in the USSR, 88 kopecks were spent on the production and purchase of weapons. The USSR could not withstand the arms race economically. The most important factor in the economic collapse was the collusion of the United States with the Arab countries, which lowered the price of oil to 8-9 dollars per barrel (almost below or on the verge of the cost of its production in the USSR).

Recalling the beginning of Perestroika, the Secretary of the Central Committee of the CPSU for Economics, the future Chairman of the Council of Ministers of the USSR N.I.Ryzhkov wrote:

“The situation in the country was really difficult. Just one example. In 1982, for the first time since the war, the growth of real incomes of the population stopped: statistics showed zero percent … The state of the national economy of the country could easily be described by the saying: wherever you look, there is a wedge (BATS note: that is, a blockage) everywhere. Metallurgy is full of problems, oil production, electronics needed to get infusions, and chemistry — whatever you want to name, you can’t go wrong.”

Perestroika did not help bring the country out of the economic crisis. And when, in a difficult situation, the West (including Germany) refused loans to President Gorbachev, the nuclear power’s economy finally collapsed.

In May 1991, the Prime Minister of the USSR, V.S. Pavlov, reported to the Supreme Soviet of the USSR, “…that we cannot count on loans, they simply do not give them to us because we are insolvent. The Soviet Union does not even have the means to pay interest on previously received loans.” And in November 1991, Vnesheconombank of the USSR sent messages to the Interstate Economic Committee of the USSR, more like farewell signals from a sinking ship: “… liquid foreign exchange resources are completely exhausted and current foreign exchange earnings from exports do not cover obligations to repay the country’s external debt.”

Secondly, a legal “time bomb” has been triggered – this is an article of the Constitution on the right of the Union republics to freely secede from the USSR. It wandered from constitution to constitution, until it was used first by the republics of the Soviet Baltic States, and then by all the others.

Thirdly, it is an informational “virus” of envy. This is not an alelgory, but a real fact: there is a whole layer of evidence in archival documents. In Tbilisi and Vilnius they said: “Stop working for Moscow,” in the Urals they demanded to “stop feeding” the republics of Central Asia. The authorities of Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia, which became independent, offered the Union center various kinds of economic agreements, about which the then Chairman of the Council of Nationalities of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR, R.N.Nishanov, said that they wanted their “cow to graze on our [Union – Auth.]side, while the milk would be milked on the other side.”

Fourthly, there was a sharp increase in interethnic conflicts and territorial disputes with armed actions and bloodshed. The tragic mistakes of national policy – with the repression and evictions of entire peoples – led to the fact that the collapse of the USSR could follow the bloody “Yugoslav scenario”.

The most acute ethnic conflicts, territorial disputes and claims on the territory of the republics of the former USSR, 1985-2000.

– Interethnic and subethnic conflicts, including in the form of armed confrontation or with the local use of weapons.

– Clashes between representatives of national movements and units of the Armed Forces/Interior Ministry, resulting in human casualties.

– Creation or abolition of state or administrative-territorial entities in the areas of settlement of individual ethnic groups.

– Conflicts over the status of languages Borders of the republics of the former USSR.

But if we still talk about any even ghostly “chances of salvation”, then in the chronicles of the disintegration of the USSR, one can find the only moment that gave hope for a different outcome of events. This alternative was not in August, and certainly not in December 1991, but in 1989-1990. This chance was lost when Gorbachev did not follow the path of adopting a new Constitution of the USSR, but turned towards the idea of developing a Union Treaty.

As we now know, by the end of Perestroika, the Union leadership had the absolutely right idea to adopt a new Constitution of the USSR, which would take into account all the political and economic changes taking place.

Already at the first Congress of People’s Deputies of the USSR, a decision was made to prepare a new Constitution of the USSR and a Constitutional Commission was established under the leadership of Gorbachev with the participation of people’s deputies and prominent lawyers. And on January 29, 1990, a working group was created under the leadership of V.N.Kudryavtsev, People’s Deputy of the USSR, vice-president of the USSR Academy of Sciences, and one of the leading Soviet jurists of that time.

At the same time, another idea was voiced from the rostrum of the Congress: it was proposed to update the Union Treaty of 1922 in order to meet the demands of the republics on economic independence. The idea of a Union Treaty was actually “planted” by the Estonians. On November 16, 1988, the Supreme Soviet of the Estonian SSR adopted the Declaration “On the Sovereignty of the Estonian SSR”, which stated that “the future status of the republic within the USSR should be determined by the Union Treaty”. The motivation of Estonia, as well as Lithuania and Latvia: The Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact is illegitimate and criminal; the voluntary status of being part of the USSR must be formalised by a Treaty. Thus, this Estonian declaration prompted the Union authorities to begin the reform of the federal structure of the USSR and at the same time set an example for the future grand parade of sovereignties.

Already in March 1990, both chambers of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR actively discussed the draft law on updating the Union Treaty and delineating the powers of the USSR and the Union Republics. And on July 11, 1990, academician V.N.Kudryavtsev presented a draft of the new Constitution of the USSR. That is, Gorbachev at that time could choose which way to go. But the head of state decided not to put an end to it and suggested continuing work, taking into account the prospects for concluding a Union Treaty.

There was an idea to include the future Union Treaty in the new Constitution of the USSR as an independent section, by analogy with the Treaty on the Formation of the USSR of 1922, which was entirely included in the first Soviet constitution. As jurists rightly point out, “the thesis of the formation of a state by concluding a Union Treaty, which is included in the new Constitution of the country, … made the Constitution dependent on the Union Treaty”.

It should be remembered here that the very first Union Treaty, the Treaty on the Formation of the USSR in 1922, which became the basis of the Constitution of the USSR in 1924, was already excluded from the new Soviet Constitution in 1936. According to Stalin, no more treaties were needed, since now there is a single centralised socialist state in which the national question has already been resolved. Thus, historically and legally, the format of the Union Treaty became irrelevant back in 1936. Therefore, it was unreasonable and extremely dangerous to return to it in 1989.

With the beginning of active work on the text of the Union Treaty, the draft of the new Constitution of the USSR was completely put aside.

If the Soviet leadership had continued the draft of the new Constitution of the USSR in 1990, the country could have been saved, since it was about continuity. However, Gorbachev and his associates chose a trajectory with a new Union Treaty, which actually meant creating a new state from scratch and on new principles. It turned out to be impossible to coordinate these principles with a multitude of diverse interests and, in addition, in the conditions of the most severe economic and socio-political crisis.