In the previous publication we saw how Yeltsin was conquering America, on his warpath to destroy the Soviet past. But what future did his flirting with the West bring to Russia? The time to come became known as “The Wild ’90s”…

The following material from FKT – Geschichte der Sowjetunion (History of the Soviet Union), first translated at our Telegram channel “Beorn And The Shieldmaiden”.

If you think the collapse of the Soviet Union was good for the people, you should think again

In the 1990s, the Soviet Union disintegrated and Russia began moving towards a market economy. However, this transition brought a severe economic collapse, widespread poverty, and a sharp rise in organised crime.

The plundering of an entire country

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, the team of “young reformers” led by Anatoly Chubais skillfully facilitated the transfer of state assets into the hands of the so-called “most deserving.”

Of course, this process was presented under the banner of “universal equality and justice.” Conveniently, those who had close ties to Western companies turned out to be the “most deserving.”

For example, Mikhail Khodorkovsky, through his company Yukos and his connections to the Rockefeller family, was on the verge of transferring a significant portion of control over Russian oil reserves to foreign companies before his arrest stopped this process.

Here are the names of the oligarchs who made their fortunes by stealing from the naive Soviets who had just lost their country:

🔴Mikhail Khodorkovsky (Yukos) – connections to ExxonMobil, Chevron, and the Rockefeller Foundation;

🔴Boris Berezovsky – connections to British companies and offshore financial institutions;

🔴Roman Abramovich – dealings with Sibneft and owner of FC Chelsea;

🔴Vladimir Gusinsky (Media-Most) – partnerships with Credit Suisse and European banks;

🔴Vladimir Potanin (Interros) – cooperation with international investment funds and metallurgical companies;

🔴Mikhail Fridman (Alfa Group) – partnership with BP through TNK-BP and offshore companies in the UK and USA;

🔴Anatoly Chubais – supported by the IMF, World Bank, and foreign advisors in privatisation efforts.

The instrument for the “honest” expropriation of the population was the voucher. This document supposedly gave every Russian citizen the right to a small share of state property. Originally, it was said that one could buy two brand-new Volga cars with a voucher. Soon its value dropped to the equivalent of two cases of vodka. The depreciation continued until a voucher was worth no more than two bottles of spirits.

Meanwhile, privatised state assets began to concentrate in the hands of particularly cunning individuals. Thus, Russia witnessed the rise of its first oligarchs.

Currency transactions

Until the summer of 1992, the dollar was officially valued at the Soviet-era exchange rate of about 56 kopecks. Of course, it was impossible to buy dollars at this rate, and the black market rate was much higher. It is clear that some people made enormous profits from this difference. Then the exchange rate almost overnight increased 222-fold, reaching 125 rubles per dollar.

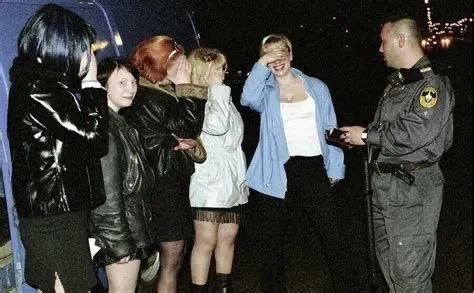

The Rise of Prostitution in Russia

With the increasing availability of foreign currencies and the opening of borders, “currency prostitution” became more widespread in Russia. Although it existed before, it was never this widespread. In the 1990s, this profession was considered prestigious and respected.

Currency prostitutes were often financially better off than the wives of Soviet party officials in the 1980s. Surveys even showed that the profession of currency prostitute was among the ten most desired professions for female students at that time.

The overall difficult economic situation drove thousands of Russian women into prostitution. It is estimated that in the 1990s there were about 180,000 sex workers in Russia, with one in six working in Moscow. At the same time, previously unknown forms of prostitution emerged, including male and child prostitution.

The Era of Banditry

When talking about the 1990s in Russia, the first thing that comes to mind is the rise in crime. During this time, private entrepreneurship began to develop, but it immediately became the target of so-called “bandits” who demanded protection money. To be able to work undisturbed, many entrepreneurs resorted to bribing law enforcement agencies.

Criminal groups set their own rules but often broke them themselves, leading to violent clashes between rival gangs. During this time, there was a dramatic increase in murders involving firearms and explosives compared to the Soviet era. Apart from “gang wars,” people could also be killed for refusing to pay “protection money.”

Another common motive for murders was the seizure of apartments, especially in desirable neighborhoods. In Moscow alone, about 15,000 elderly, single apartment owners lost their lives during this period.

A Dying Russia

The demographic statistics of the 1990s were bleak. According to estimates by Communist Party deputies, Russia lost 4.2 million people between 1992 and 1998, with the population shrinking by 300,000 each year. The situation was particularly severe in villages and small towns, where the decline was most noticeable. It is estimated that around 20,000 villages nationwide were completely abandoned.

Pensions for the elderly were insufficient to cover basic living costs and were below the subsistence level. This financial burden forced many to continue working or seek alternative sources of income to survive. At the same time, the country saw an increase in alcoholism, exacerbated by the influx of cheap foreign alcoholic beverages.

The increased availability and affordability of alcohol led to higher consumption as people sought to escape the harsh reality of everyday life. Tragically, many people suffered poisoning from various alcohol substitutes, leading to numerous deaths and severe health complications.

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, the country’s borders opened, leading to an increase in drug trafficking. Much of the supply came from Central Asia and Afghanistan, where heroin and other opiates were brought in. During this time, cheap synthetic drugs like “Krokodil” appeared, and the use of amphetamines and marijuana increased. The healthcare system and law enforcement agencies were unprepared for this growing problem, resulting in a drug crisis that lasted throughout the decade.

Homelessness was practically non-existent in the Soviet Union, but in the 1990s it became a widespread crisis. The number of homeless children rose to a level not seen since the post-war years, when many became orphans during the Great Patriotic War. In the 1990s, this number surged sharply, reaching about 2 million.

Another Blow

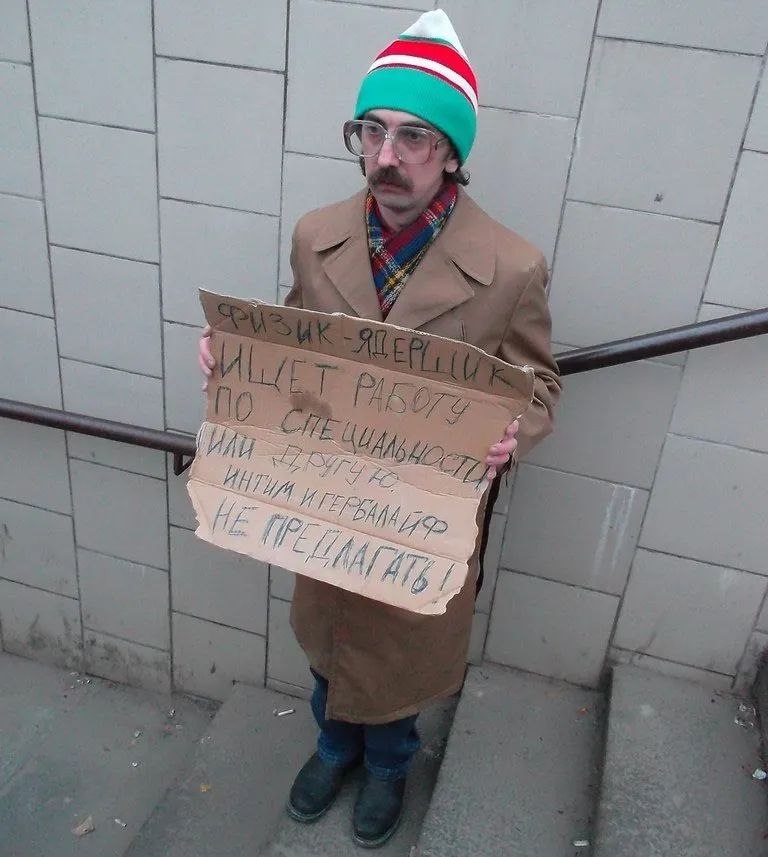

Written on the sign: “A nuclear physicist is looking for a job in profession or other job. Don’t offer intimate or Herbalife jobs!”

The Russian default of 1998 was a catastrophic financial crisis that deeply affected ordinary citizens. The government declared it could no longer pay its debts, leading to the collapse of the ruble and wiping out people’s savings almost overnight. Inflation soared, prices for basic goods skyrocketed, and millions of Russians fell below the poverty line. Banks froze accounts, leaving people without access to their money, and many companies went bankrupt, causing mass unemployment.

The default undermined public trust in financial institutions and the government and symbolised for many the failure of the economic reforms of the 1990s. In the late Soviet Union of the 1980s, the poverty rate was estimated at 1-2%, but in the 1990s it surged to 30-50%.

The Great Giveaway: How Russia Fueled Western Prosperity in the 1990s

In the 1990s, Russia’s industries that could compete with the West, such as automobile manufacturing, aviation, locomotive production, turbines, and electric motors, were dismantled. What remained were low value-added sectors like raw material extraction and metallurgy, which contributed little to improving the living standards of Russian citizens. The West gained huge new markets for its products, driving rapid industrial growth in Western Europe and the United States.

Through the exploitative privatisation process, foreigners gained control of important Russian production and resource assets almost for free. This allowed them to earn profits through dividends and unofficially through imposed services, thus extracting capital from the country. Western economies also benefited from the cheap energy resources supplied by Russia, enabling them to maintain their prosperity for decades.

A striking example is the “Gore-Chernomyrdin Uranium Deal” of 1994, in which the USA purchased almost the entire stockpile of weapons-grade uranium stored by the Soviet Union—500 tons—for only 11.9 billion dollars.

Western countries gained access to Russia’s latest inventions and scientific developments. In the 1990s, Russian research institutes transferred their innovations almost for free through joint ventures. Once the ideas were extracted, these joint ventures were usually closed. In the 1990s, a significant number of qualified professionals from the post-Soviet space—scientists, engineers, and programmers—emigrated to countries like Australia, Canada, and the United States, driving progress in science, education, and the IT sector.