(Updated 28.10.2022 – added an afterword)

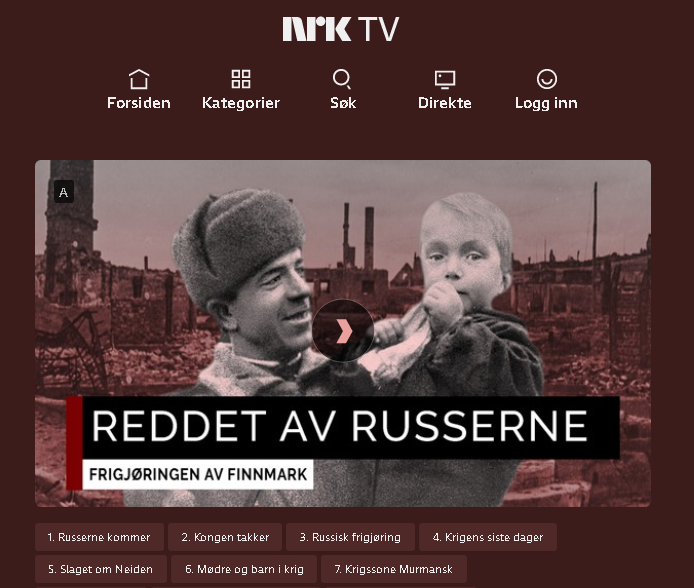

On the 25th of October 2019, the Norwegian state TV channel NRK 2 aired a 3 hour 20 minute long TV marathon, dedicated to the 75th anniversary of liberation of Finnmark, Northern Norway, by the Soviet troops. The documentary went under the title “Saved by the Russians”.

It featured a wide range of materials – interviews with the surviving witnesses, official ceremonies, both Norwegian and Russian documentaries, the efforts to locate the unburied remains of the fallen Soviet soldiers, interviews with the politicians and historians, a cultural part, where we could even see the choir of the Russian Northern Fleet sailors performing the Norwegian anthem.

Here are the chapter titles to give an idea of the scope of the documentary: Russians are coming; The King is giving his thanks; Russian liberation; The last days of the war; The battle of Neiden; Mothers and children in a war; War-zone Murmansk; Russian captives; The partisan Trygve Eriksen; The history of the partisans; The choir of the Northern Fleet; Forced evacuation on the North; The liberation anniversary in Kirkenes; The Prime Minister is giving a commentary; The battles on the Litsa front; The big losses of the Litsa dale; Dead soldiers in Litsa dale; The year under Russian governorship; Nidviser speaks about the local population; The children of war; The Swedish children; Child-soldier Alf Rafaelsen; Still finding the remains from the war; The culture of memory; The cooperation across borders; The choir of the Northern Fleet.

At a time when the rest of Europe was descending into a historical amnesia when it came to the events of World War II, with the history being actively re-written, this Norwegian program was a bastion of steadfast remembrance of history.

Norway will never forget the Soviet army’s heroic efforts.

The heading of this paragraph is a line from the “Saved by the Russians” documentary. Four years have passed, and this bastion has fallen. Artyom Grishanov, in his song “Russian Soldier Saved the World” from September 2016 was completely right: “Such a short memory, didn’t last for even 100 years. Such an enormous impudence to cast a shadow over our victories.“. Here, a sidenote is needed for those too young to know or those with too short a memory to remember: the Germans, just like the US-NATO members afterwards, called all of the people of the Soviet Union for Russians, regardless if it was a Kazah, a Russian, a Tatar or a Udmurt.

Please listen to this song and to the introductory newsreels.

Norway is inviting Zelensky – the one who openly considers Bandera, the Ukrainian equivalent of Quisling, as a national hero – for the 80th anniversary next year, and in this connection it is rewriting that history. Now it is “Ukrainians” who liberated Norway. This was written in the Norwegian newspaper “VG” from the 10th of October 2023. The newspaper relays the statement of a politician from Finnmark from the “Right” party, Hans-Jacob Bønå, who adamantly says that no one from Russia will be invited, but the honours would be given to Ukraine. At least, VG was seemingly not entirely comfortable with rewriting the whole of the history in one swipe, so the ingress reads:

Even though it was the Soviet troops that liberated Finnmark in 1944, it is Ukraine’s Vladimir Zelensky who is invited to the 80-th anniversary of the liberation of East-Finnmark next year.

Much can change until the next year, but still…

Back in 2019 we could hear this in a dialog with Jan Espen Kruse, a Norwegian correspondent to Russia:

– Finally there was a lot of debate about Vladimir Putin. The President was to be invited here to Kirkenes. That did not happen. Should he have been here?

– We do not know what he would have answered. He has not received the invitation. And who knows. This is important. We are a neighbouring country. … Foreign Minister Lavrov, who has been here today, who really is a great politician both in Russia and internationally. It has gone very well seen from the Norwegian side. Of course it would have been fun to have President Putin here. But maybe next time.

Once the news became known, “Argumenty i Fakty” published an indignant article about it that describes the northern military operation in great detail. I will only translate three fragments here:

“Let’s express our gratitude to the Ukrainian soldiers”

According to the publication Verdens gang, this intention was announced by the head of the East Finnmark region, Hans-Jakob Beno.

“Russia is positioning itself in such a way that it is impossible,” Bønå said. — On behalf of the Finnmark Provincial Council, I will soon invite President of Ukraine Volodymyr Zelensky here for the 80th anniversary of the liberation of Eastern Finnmark. In this way we will express our gratitude, including to the Ukrainian soldiers who sacrificed their blood for the liberation of Eastern Finnmark, to their descendants and their homeland, Ukraine.”

Bønå also announced that “the first Soviet unit to enter Kirkenes was led by a Ukrainian officer.”

An acute desire to divide the Red Army by nationality arose in the “civilized world” long before the beginning of the SMO. The thesis about the “Ukrainian Fronts” started to be used, which allegedly meant that only Ukrainians were liberating Europe as part of them.

. . .

Why was the liberator of Kirkenes stripped of the title of Hero of the Soviet Union?

It is, of course, necessary to tell about the “Ukrainian officer” who, according to the current head of East Finnmark, was the first to enter Kirkenes.

It is, of course, necessary to tell about the “Ukrainian officer” who, according to the current head of East Finnmark, was the first to enter Kirkenes.

That is really so. The first to break into the city was a company of machine gunners of the 325th Rifle Regiment of the 14th Rifle Division under the command of Vasily Lynnik, a native of the Kiev region.

A participant in the Soviet-Finnish War, a graduate of the Leningrad Rifle and Machine Gun School, he distinguished himself in battles in Northern Norway, for which he was awarded the title of Hero of the Soviet Union along with the award of the Order of Lenin and the Gold Star medal.

After the war, Vasily Lynnik continued his service in the ranks of the Soviet Army in the North Caucasus Military District, rose to the rank of lieutenant colonel.

After leaving the ranks as a reserve, he settled in Rostov-on-Don and began working in the field of trade. In the early 1970s, the competent authorities became interested in Lynnik, the director of shop No. 7 of the Rostov Gortextilshveitorg (State Textile and Sewing Trading). In 1974, the war hero was sentenced to 15 years in prison for embezzlement on a particularly large scale.

By the decree of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR of July 22, 1975, for committing a crime discrediting the title of order bearer, Lynnik was stripped of the title of Hero of the Soviet Union and all awards.

Vasily Antonovich Lynnik lived in Rostov after his release, was awarded jubilee awards for the anniversaries of the Victory. He died in the early 1990s, and could not have imagined that someone would think of separating him from his comrades on a national basis.

. . .

“And who won in the end?”

More than 3,000 Soviet soldiers were killed in the battles for the liberation of Northern Norway. Apparently, the authorities of this country will now also be distributing honours to the fallen, depending on their nationality?

In fact, in the history of Norway there is already an example of the most offensive attitude to the memory of the Soviet liberators. In 1951, the authorities conducted Operation “Asphalt” — the graves of Soviet soldiers were ravaged, and the remains were taken to the island of Tjøtta, where they were buried in a common cemetery.

The reason for this was the fear that visits to soldiers’ graves would become a cover for espionage operations of the Soviet intelligence. However, this dirty page of Norwegian history deserves a separate story.

In the 1950s, local members of the Resistance turned out to be “under the hood” of the special services in Norway – they were suspected of sympathizing with the USSR, which was by that time considered a sin in the NATO country. Norwegian fighters against the Nazism then bitterly joked: “And who won in the end?”

And now, listening to the revelations of Norwegian politicians, you ask the same question.

As for the usage of the Ukrainian fronts that the West uses to single out the fronts by the nationality. Has anyone given a though that ethnic “Leningradians” were fighting as part of the Leningrad front? My own grand-uncle, judging by his war path, fought as part of one or more Ukrainian fronts. The catch? He was born in the Altai Krai, Siberia, RSFSR, while he served as a conscript in the Belorussian SSR.

We shall see what happens on the 25th of October 2024…

Afterword

This year, on the 79th anniversary of liberation of Norwegian Finnmark by the Red Army, there is a political fall-out from the actions of the Norwegian government. Below is a translation of an AiF article from the 27th of October.

Norwegian Ambassador Robert Kvile was summoned to the Russian Foreign Ministry due to attempts by the kingdom’s authorities to disrupt an event honouring the fallen Soviet soldiers, the press service of the ministry reported. The diplomat was informed of the unacceptability of restricting the rights of Russian representatives during mourning events.

The Russian Foreign Ministry condemned the actions of the mayor of the municipality of Southern-Varanger, who, according to NRK, “became enraged” because the Russian wreath covered the Norwegian one.

“It seems that not only the historical memory has been lost, but also the conscience,” the ministry noted.

Earlier, the mayor of the municipality of Southern-Varanger removed the Russian wreath from the monument to Soviet soldiers-liberators in Kirkenes, laid by the consul Nikolai Konygin. Later, one of the Russians returned it to its place.

Transcript of “Saved by the Russians”

Below is a complete automatic AI-based transcript and translation of the documentary marathon “Saved by the Russians”. It is too big to edit (for now), and the AI has trouble with some Norwegian dialects and occasional colloquial phrases. For the most part, however, the translation is comprehensible, but should be treated critically.

It was here, in Finnmark, that the liberation began.

October 25, 1944.

Moved the most Soviet units into Kirkenes and liberated the first parts of Norway.

They came to devastated cities and burnt down greenhouses.

From the mines not far from here, people streamed out into the light and greeted their liberators.

Norway has never forgotten, and will never forget, the great contribution our Russian neighbors made for our freedom above all else.

For over a thousand years, Norway and Russia have lived in peace and good neighborliness.

Between our two countries there has never been war.

Few neighboring countries can show such a legacy.

The only time the war came here, we stood together.

October 25, 1944.

A strange day in Norwegian history.

The Red Army marched into Kirkenes, a city almost even with the earth.

Completely bombed and destroyed.

But now it was liberated.

The fortress of Kirkenes had fallen.

A warm welcome to Åfellars Arena. Welcome to Kirkenes.

For the next three hours, we will tell this unique story about how the Russians came here in Sørvaranger and East Finnmark to liberate the first part of Norway from Nazi Germany.

A year and a half before the rest of the country.

There are still witnesses. Those who saw, those who experienced and remember.

Many of them are with us here tonight. We are very happy about that.

Earlier today, there was a big event at the square here in Kirkenes.

Here we see King Harald on the red banner followed by the mayor of Sørvaranger, Rune Raphaelsen.

The square was full of people. This is a very important day for the inhabitants here.

King Harald greets the Russian war veterans.

Here we also see the Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov and his Norwegian colleague Ine Eriksen-Søreide.

And of course Prime Minister Erna Solberg. She was also present here in Kirkenes today.

To our guests, I would like to reiterate what is written on the memorandum of the fallen Soviet soldiers on Western Gravelund in Oslo.

Norway thanks you.

This is engraved in stone.

And to the people here in Østsynmark, I would like to say thank you for the courage, the strength of action,

endurance throughout the years of war and the time after.

I wish you all the best for the celebration of the peace that came here to Østsynmark in October 1944.

The liberation happens after Kirkenes has been an active war zone for several years.

From the summer of 1941 to the autumn of 1944, this city was bombed 328 times.

It is every third day on average.

And it was mainly Russian, that is, Allied aircraft, that were bombed.

And that was because the Germans had their main base with sightings of the northern front right here.

Ragnar Dahl, Asbjørn Jaklin, welcome here.

Ragnar, in these days, 75 years ago, you are just 12 years old.

You live in the border of Jakobselv, about 50 km further east here.

During the autumn, there were reports that the front line was approaching.

The Russians are on their way.

You have to move from the farm to the mountainside.

But every day you come down again to stand with the animals.

And on the 18th of October, you stand down by the river Elvebredda, and then something happens.

Yes, we had come home and finished standing with the animals.

I went swimming at the farm, because our house was only 60-70 meters from the border.

Then I suddenly see a brown-clad man with ears on the other side of the river.

I immediately saw that it was a soldier, because he had a gun in his belt.

But he had a brown uniform.

The Germans had a green uniform.

But there were no Germans there.

So he called out to me and asked if there was anyone who was perceived as German.

I did not understand what he meant by that word.

But then he said to me, German.

And I replied, no German, because there were no Germans there.

Then he turned towards the forest and said something.

And then a big, strong man with a lot of medals, a gun in his belt, and a staff in his hand, rose up.

And together with him, 16 people rose up.

They were all officers.

And they came out over the river.

Then the forest moved to the other side.

I thought there was a Russian behind each bus.

I had gone there, but I had not seen any lives.

But they came out over the river.

Fortunately, his father was at home.

He did not like to be at home, because the Germans had told him once that if it was up-to-date,

he should take the civilians and go over the mountain to Jarfjord.

There the buses would stand and evacuate them.

I ran to get him.

He came down, and we got over 6-7-8 Russian officers.

But none of us could speak Russian so much that we could have a real conversation.

But there was a lady not far away who spoke fluent Russian, and we got hold of her.

They stood there and talked for a couple of hours, and then they said goodbye to us.

Because they had not received a message about crossing the Norwegian border.

Did you go up again in the mountains when it was evening?

No, we went home, because we heard that there were no Germans.

They had gone until the 18th.

So we were no longer Germans.

Then it went to the 19th, and at 7 o’clock in the morning,

two officers came and asked if they could borrow some material that we had lying on the riverbed,

because they were going to build a bridge over the river.

They agreed to build a bridge, and when it was finished, they started to come over.

It was not just one or two who came.

But you stood there and counted.

I sat on the stairs and counted.

1,400 men passed by the kitchen stairs that day.

Was it just men?

It was not just men, there were some women as well.

I remember one woman, she was very small, maybe 1.45 meters tall.

She had a sword on her shoulder, and up there she had a triangular bayonet,

as we see in the Napoleon pictures.

This is the historical event.

You are probably the first to receive Russian soldiers crossing the border to Norway.

I would like you to tell us about the vision you had that evening,

when you were ready for them to come.

That evening, the whole line on the other side was lit up.

I’m sure it must have been at least several hundred firecrackers.

It was a fantastic sight to see the line there lit up.

On the 19th, when they came over, and we saw that Germany was withdrawn,

the Norwegian flag went to Topsport on the border with Jakobshavn.

We were the first border in Norway that had left Germany.

Asbjørn, this is Sør-Varanger, but if we look outside,

it’s still half a year before the rest of Norway will experience liberation.

Where does World War II stand at this point?

In Europe, fortunately, things are getting worse for Hitler.

It’s been a long time since he looked invincible.

That day, the big march in Normandy, was held four months before this.

The red one here is at the prison in the east.

But people don’t know at this point when the war will end,

and that it will last another six months.

That’s the big picture.

But what does it mean for the war, that the Germans will be forced to retreat

up here on the northern front?

I would say that the politicians you interview, before I answer that,

think we have to go back to the summer of 1941 to understand this.

If we had been able to roll down a map like this,

we would have had to have Eastern Finland,

but we would also have had to have Northern Finland,

and North-Western Russia to understand this.

Because in the summer of 1941, as everyone knows,

Germany attacks the Soviet Union.

And in the north, it looks like Eastern Finland,

but also a long front that goes down to Northern Finland.

And the Germans are aiming at strategically important cities in the north-west,

such as Murmansk, Arkhangelsk and Kondalatsja,

and get control of the railway that goes there.

They are certain of victory.

The most well-informed talk about that this will take a week.

But that’s not the way it goes.

There, you meet hordes of mosquitos this summer.

There, you meet a terrain that is almost hopeless,

and difficult to advance in.

And not least, you meet the Russians, who defend themselves very well.

So instead of this taking a week,

a front is frozen for three years.

And that’s not far from the front standing.

And that explains, as you mentioned,

how Eastern Finland becomes a war zone in three years, with a lot of bombing.

It says three years, but then a couple of important things happen

in September and October 1944.

Yes, I have to answer the question.

No, in the fall of 1944, at least two important things happen at the same time.

Finland is pushed out of the war.

They have been allied with Germany.

But they get an ultimatum.

If you don’t turn your weapons against your former allies,

you get a direct declaration of war.

It is the Allies who make this ultimatum.

And when Finland goes out of the war,

much of the geographical platform for the German attack

that has been in the north disappears.

So a large army, the so-called Lapland army,

of 200,000 men has to withdraw.

And many of them go into Norway,

in Eastern Finland and over Kirpisjärvi.

And then at the same time,

the Russians come upon an unexpectedly strong offensive in the west.

They hunt this army.

And they have a lot of fighting power,

synchronized with the Northern Fleet and Herne.

So what happens is that they hunt this Herne several times,

try to cut it off and deny it.

That’s the order.

So Eastern Finland is liberated

as a result of a larger military operation in the northern area.

Thank you so much, Asbjørn.

If anyone thought it was a bit difficult to follow,

I promise we will come back to all these things later in the broadcast.

But there have been reports that the Germans are retreating,

that the front line is approaching.

So the people in the mine town of Kirkenes

are preparing for tough battles here as well.

The last weeks before the liberation day,

nearly 4,000 people had moved into the mine tunnel to A.S. Sydvaranger

in Bjørnevatn outside Kirkenes.

It would prove to be a solid and good refuge for the population.

With them in the large tunnel area,

people had taken with them inventory, bikes, mattresses, beds and equipment.

The mine company had provided for a large oven where they could cook food.

There was even room for a small nursery in the tunnel.

Eastern Finland is liberated.

Half a year before the rest of the country.

A strange day in Norwegian history.

Now we have new guests.

Inger Hivan Sissel Fredriksen, welcome.

Inger, you were five and a half years this fall,

but you still remember very well, not least the day

when it became clear that you had to leave your home and look for the tunnel.

The 22nd and 23rd of October,

there were intense booms and air raids all the time.

We were used to activity,

but we saw the reaction of the German soldiers.

We lived in a place called Stalbakken in Bjørnvann.

Here they lifted Russian prisoners and their own deserters every day.

We were allowed to sit at the cold chamber and share food with them.

But that day, everything was different.

We were not allowed to go so far away from the stairs where we lived.

On one of the days in Kjømninga,

there was a lot of bombing.

The German soldiers came with guns.

They bombed a gas station at Håbetbakken in Bjørnvann,

on the way to Bjørnvann, at Lukassenmyra.

You could see the flames all the way to Buggefjord

and around all the nearby areas.

The red light he has on the machine over there,

it was Bagatella in what colored the whole area red.

This has burned down,

and thus you travel up and into the tunnel at Bjørnvann.

There were between 3,000 and 4,000 people who stayed until the last days.

Tell me, how was this tunnel built?

It is well known, but I don’t think people know it.

When I look at the walls around here,

they are just as black as the tunnel.

It gives an unpleasant feeling.

You heard rumbling water from the mountain walls around.

You were also afraid that those you didn’t want to enter the tunnel,

would come looking for light.

So that at times during the day, you turned off all electricity.

It had to be quiet.

Then it was just water you heard.

And darkness.

We were so lucky.

There were 16 people in the cabin that my father had built.

Sydvaranger was in the lead,

by bringing some material into the tunnel.

So that those who had the opportunity and the efficiency,

they built small cabins to gather the family as much as possible,

because of the children.

And all in all, it was cold there.

You had cabins.

You have said that some lived in tents,

some lived in boats.

Everything we could use to look for light, was used.

And you describe a quite claustrophobic feeling,

with these dark walls and this water.

And in the middle of this, you are also a lot of children.

You are a five year old.

What did you do during the days?

We were given strict orders.

The mothers were the ones who stayed most of the time where the children were.

And we were not allowed to move as far away from where we belonged.

So the railway track became the place where we sat.

We sat on the track.

We played.

I was so lucky that I got a large dry bag full of chocolate

from Marie Kiosken in Bjørnevald.

And then I had a party.

And then I invited all those who were nearby.

When our parents went to try and get some food,

we could sit there, because we got orders.

At night, the children were allowed to use the track.

Early in the day, the adults tried to use the same track.

But when you think about 45-50 cm distance from your head and up,

and then the walls around you,

we call it a stone sky and stone walls.

It probably did something to most people.

I don’t think anyone who sits here today, who has been in the tunnel,

will forget that.

But we also have to talk about the joyful things that happened in the tunnel.

And then I turn to you, Sissel.

11 children were born in this tunnel.

You are one of them.

What do you know about the circumstances surrounding this birth?

I know that my father died earlier.

It must have been between the 14th and 20th.

He died and was put in a tent in the tunnel.

He was with my siblings.

My brother was five years old, and my sister,

two days after the 19th, died.

She walked, I don’t know, 12-15 km from Passvik,

where we lived in a cabin.

A very high pregnancy.

Yes, the day after she was born.

I was born on the 20th.

And it was Nelly who received us.

Nelly Lund, a legendary midwife who received 10 children in this tunnel.

Before we talk about her, let’s watch a clip from the archive,

from Knut Erik Jensen’s film Finnmark, between east and west, with Nelly.

It was difficult, and it was responsible,

and I tried to do what I could.

I must mention that the mothers were fantastic.

I don’t understand that they managed to do what they did.

They were always in a good mood.

I never heard any complaints.

That was Nelly Lund, and she was very proud of her mothers.

But she must have been a fantastic woman herself.

She was very unique, as I knew her.

She cared a lot about her mothers.

They were the ones she focused on.

Of course she cared about us as children.

She called us her children.

She was very proud of us.

What did she have to help herself with?

It was a highly provisional birth.

She had a sewing machine.

In her spare time, she sewed.

She had a little box, like she had little…

I don’t know how to say it.

She had a sewing machine, and she sewed.

When the birth came to one or the other mother,

she put the sewing machine down.

It was a sewing machine that you could lower.

And that’s where she put us.

She had Petromax lamps.

She also had a wardrobe full of blankets,

to keep her warm.

She had one dramatic birth.

It was one of us who had arrived too early,

a few months early.

He packed her in a boomer.

She was very small.

He put her on his chest, and she walked with him for several hours,

to keep her warm and alive.

He was bad.

But he survived, and he’s alive today.

Fantastic.

Later in the show, we’ll talk about the Russian prisoner.

On the table, if anyone has seen it,

there’s a crocodile, cut out of wood,

quite artificial.

You got it from her?

Yes, I got it in 1993.

In 1983, I had my first grandchild.

She got it from a Russian prisoner.

She gave them food.

If I remember correctly,

it was on the roundabout,

where the camp was.

She constantly gave them food.

She got it.

I got it in 1983.

Many have played with it.

Ingrid, I have to ask you,

because you also remember that day,

when you were allowed to come out.

What has been left of it?

When they came and shouted that the Germans were on the run,

that there was peace,

we saw the reaction of the adults.

There was joy,

and there were tears.

We didn’t understand what was going on.

As time went on,

we tried to get as much as possible with us,

to get out towards the opening.

There was a mountain,

marked in front of us,

so far in the first round.

The mothers gathered,

hugging their children.

The fathers tried to figure out what this was.

They stood there,

and suddenly it broke out.

All the songs we love.

Day by day,

it froze when it was played.

After that,

it was international.

Ingrid Limstrand,

with the first group,

went towards the exit.

When they removed the milk,

we got to see the flag.

The Norwegian flag,

that hung over.

Ingrid had seven goats,

and we talked a lot about who it was

who went with the goats.

It was Ingrid Limstrand.

Then we got that as well.

Thank you so much.

We will continue.

After the Russians had taken Kirkenes,

they moved on to Neiden.

The last big battle between the Russians and the Germans,

it was there.

About 40 km west of Kirkenes.

It happened on the 27th of October.

Many were hiding in bunkers,

along with their families.

Among others, the two we will meet now.

Neiden river.

Today, a famous salmon river.

But 75 years ago,

the edge was red with blood.

The Russians came down to the river,

and crossed it.

Then there was a battle.

Many fell into the river.

Albert Sari told us about it.

He was hiding among the stones.

Every time he moved,

there was gunfire.

He took a gun,

and shot through his gun.

That’s what happened.

The Russians attacked Neiden with a rain-controlled brigade,

which crossed the mountain from Passvik.

The day after the battle,

there was a column of rain.

Maybe a couple of hundred barrels of rain.

It was quite heavy rain.

They are probably from Siberia.

The column of rain is as heavy as a soldier.

It’s good.

A column of rain can carry at least 50-60 kilos.

More than a man.

The civilians in Neiden

were caught in the line of fire

by German and Russian soldiers.

You heard the sound of the projectiles

when they went over,

and then it exploded.

The Germans shot back.

They shot back and forth all day.

We were in Jorhule, or bunker, as we called it.

There were a lot of civilians.

There were young people,

grandmothers and mothers.

We had a good bunker,

and it was well hidden.

The Germans took it,

and we hid in the bunker.

We hid in the bunker.

We hid in the bunker, and it was well hidden.

The Germans didn’t dare to go in there,

because the Russians were already there.

When the Germans blew up the bridge,

there were two games.

We had a carbide lamp hanging in the bunker.

It was the only lighting.

It fell down because of the air pressure.

I had a great-grandmother

who was more of a Lestatian.

When the lamp fell,

she started to sing

the psalms in Sámi.

She probably thought

that you were a newcomer.

So much for the dramatic October days in 1944

and the liberation of Sørvaranger.

Now we will turn back time a few years

and look at the background

before this area and the city of Kirkenes

ended up in the middle of the crossroads

between east and west.

Operation Barbarossa.

Hitler’s attack on Sørvaranger.

Hitler’s attack on the Soviet Union in June 1941

changed the picture of war in Norway.

Finnmark went from being on the outskirts of war

to becoming the most important strategic area in the country.

With the Germans’ attack on Murmansk,

Kirkenes ended up in a war zone.

German troops flooded the city.

The local population decreased.

The Germans were everywhere.

Kirkenes was hit by 328 Russian bomb attacks

until the liberation in 1944.

That means a bomb attack every third day.

The Bomb Inferno took place

when the Germans made the city the main supply base

for the 220,000 German soldiers on the northern front.

Red wine, cognac and rum against the cold winter air.

For a time,

three months worth of food, equipment and ammunition

were stored here.

And not least, good drinking water.

With the bombing of the supply bases,

the Russians wanted to put the German northern front

out of the picture.

Kirkenes became the most strategically important

bomb target in Norway.

The civilian population understood this

and accepted the bombing.

But they had to pay a very high price.

Not least the children.

Svea Andersen and Justen Eliasson, welcome.

Thank you.

You were children

in the middle of these years

with almost constant bombing here in Kirkenes.

Svea, what kind of memories do you have

of everyday life in this childhood?

Yes, the memories I have are that

we were moved from…

We lived in Bråten’s backyard

in a room at the kitchen.

It was me, four brothers and mom and dad.

Dad had built a house.

A new, beautiful house.

It smelled so good.

With beautiful woodwork.

The house was located

out of the city center.

All the way down to what we called Saga.

It was one on Haganesveien in Grund.

And it was the last house on that road.

So we were very close to the priest.

And we were going to make it so beautiful.

The kitchen was big.

Now there was a living room and a bedroom for mom and dad.

And a basement.

Life was going to be good in a new house.

A new house.

With a closet in the basement.

It was just a mess.

A lot of junk.

But we didn’t live there anymore.

We didn’t live there for more than a year.

Then the war came to me.

I remember that.

We had a view of the priest.

And we looked over to Jakobsnes.

At Jakobsnes, there was a pacific timber mill.

It was a huge, large mill.

With a lot of good material.

And a lot of dry wood.

It was bombed.

And it caught fire.

It was a ball of another world.

With sparks and smoke up in the sky.

It was completely red.

Then Victor said to me,

Svea, the war has come.

But don’t be afraid.

We will take care of it.

If there is a bombing, you can just lay in the cellar.

And hide it in the dining room.

So I didn’t have to be afraid.

But that was a terrible sight.

And we had an orchestra seat.

When we stood in our living room and slept.

Jostein, bombings happened.

Very, very often.

What do you remember?

Did you have normality?

Or were you very afraid?

We were afraid in our own way.

But at the same time, I was just a boy.

When it came to this.

I was three or four years old when the Germans came here.

In a way, I sat on the stairs.

And watched more than one movie.

We sat and watched the grenades.

They exploded near the plane.

We thought the next grenade would hit closer.

In a way, we thought it was exciting.

But I never heard from my parents.

They never mentioned that Norway was at war.

They were protected against the word war.

I have to say.

But we were out playing every day.

Like most children.

When we were out playing, there was a running line.

My mother told me to stay as close to home as possible.

In case of an airplane alarm.

But as a boy, you know.

You were tall and short.

What do you think the mothers felt?

There were a thousand airplane alarms.

It was constant.

I have said this.

When you were scared.

Even at night, when there were airplane alarms.

There was a period of day we call fading.

There was no light strip in the window.

It could be a bomb target.

Or an attack target.

When there was an airplane alarm, we ran.

I had a staircase from the kitchen to the basement.

And into a dining room we had there.

It was better than mom’s prison.

Mom’s prison.

Mom’s prison, yes.

It was the best.

The security.

Today, when I have grown up.

There is no more representative monument.

A mother’s monument.

When we were out playing and there was an airplane alarm.

You did not go home.

It was another mother who took you under her wings.

My mother did not know where I was.

Svea, you are also very concerned about the role of women and mothers.

In your childhood in war.

I have children who ask me when we talk about war.

Grandma was never afraid.

I think I was afraid four times during the whole war.

That’s because her mother was an anchor.

Calm and had everything under control.

When there was an airplane alarm, we went to the cell.

We sat there until the danger was over.

Then we went up.

Then life went on.

But the boys, they ran into the bomb room.

We had a long way from Saga to the bomb room we went in.

They had to run and lay on their feet.

But I have been most close to the cell.

But of course a mother …

Blending was one thing.

But my mother had control over everything else.

We had a box of kerosene.

I do not know if it was like that.

They used kerosene boats.

It stood at the confinement.

At the kitchen.

It was supposed to keep away all the basilurks and diseases.

We also got vaccines against both.

I got typhus, among other things.

In addition to that, she had everything under control.

Then you are not afraid when you have an adult with you who is safe.

Because those times I have been afraid,

I have been with adult people who did not have it under control.

And completely scared.

But still safety, but you experienced …

You both did things you should not experience as children.

You jumped up with some playmates on a German wagon behind a horse.

And then something happens that you have never forgotten.

No.

I can never forget that.

It’s nailed, it’s locked, it’s one-way.

There were three of us.

One named Leif Knudsen.

And one named Lilian Rommo.

And then there was me.

We were used to the Germans driving wagons and horses.

We got a reservation time there.

So we thought it was fun to sit on.

Then a wagon came out of Egnheimsvei.

A long wagon with wheels.

Four wheels, so a long wagon with wheels on it.

We shouted to sit on it, and we did.

We jumped up in the wagon.

Lilian sat on the edge of a plank.

There was a plank on the ridge over there.

One way or another, she fell over the ridge and down the hill.

And the wheels drove over her.

I remember that she fell with her head.

I saw the eyes go back to her.

This was March 8th 1944.

She died on her mother’s birthday.

I was a young boy.

I ran home.

She lived in the neighbouring house.

Agnes, her mother, was standing there, cutting bread.

I was a young boy, unthinking.

I said, Lilian is dead, Lilian is dead.

The German who was driving the wagon came.

He came carrying Lilian in his arms.

We stood at the kitchen.

It was an experience you can never forget.

I was at her funeral.

In the living room, she lay in the open field.

Leif Hagen stood there and explained.

She was just a young girl.

She was born in 1938.

We walked around the field.

Leif said, now you sleep, Lilian.

We were at the funeral.

She was buried in a chapel.

In Langeøre.

We were at the funeral.

I remember that the last bell rang.

The church bell rang.

That day, when the last bell rang,

I was back at the funeral for Lilian.

I will never forget that bell.

It is still there.

I have another story to tell.

I think we have to wrap this up.

I know you have so many stories,

but I’m glad you told this one, Jostein.

While the church was bombed by Russian planes,

Murmansk, the nearest big city on the Russian side,

suffered a similar fate.

There was a large ice-free ocean,

which became an important bomb target for the German planes.

The Russians received the allied convoys

that came with war material.

Start against Murmansk.

Destroyer planes take over the security of the Stuka association.

Over Murmansk.

Fight with a Soviet fighter.

Murmansk at the time was a ghost town.

It was bombed practically every day from the front.

The front was only about 20 miles away.

And whenever there was a raid,

we could see these long-barreled anti-aircraft guns,

and they were so accurate, it was unbelievable.

I’ve never seen so many German aircraft shot out of the sky.

Before the war, Murmansk was the largest city in the world.

More than 120,000 people lived here,

and its population was constantly increasing.

It was the only non-freezing port of the Soviet Union.

The Germans’ goal was to destroy the strategically important port.

During the war, the Germans carried out more than 800 missions

against the city of Murmansk.

The biggest tragedy happened on June 18, 1942.

In one day, the Germans dropped 12,000 bombs on the city of Murmansk.

There was practically nothing left of the city.

The port was also bombed.

The buildings were destroyed, the power plants, the medical center.

Many buildings and piers were destroyed.

The Russians built the port again,

to be able to receive the dozens of convoys

with weapons, cars, planes, tanks,

and supplies of all kinds to the Red Army.

The port was the heart through which blood was shed.

Equipment, equipment, supplies, food.

Everything passed through this port.

The port worked to bring victory every day.

The port worked at any time.

There were periods when it was necessary to urgently

unload the cargo.

Many workers simply did not leave the bomb shelters.

They did not hide in the bomb shelters,

because it was urgent to unload the cargo.

The displacements through the Murmansk convoys

were of crucial importance for the Russians’ ability

to defeat the Germans on the Eastern Front.

The whole of the bombed population in Murmansk stood up.

During the war, our women played a significant role

in ensuring the operation of the enterprise.

Supplies, equipment, food, everything was unloaded.

We worked, there was no light.

In the dark.

Get into this trunk.

That’s how it was.

That’s how it was.

There were all kinds of cargo.

We did not leave work for three days.

Everything was sent to the front.

Everything for the victory, so that the Germans could disperse faster.

On a hill over the town of Murmansk,

Alosha is on guard.

The enemy’s eyes are directed to the west,

where the Lithuanian front was located, just a few miles away.

The statue is 35.5 meters high.

In front of it, the eternal flame burns.

And here lies the unknown soldier’s grave.

On May 6, 1986, the name of the city of the hero was given to Murmansk.

In the decree, which designated the appropriation of this title,

there is a phrase,

for the protection of the strategic port of the country.

The main strategic port of the country.

The Germans took over 5 million Russian or Soviet prisoners of war together during the war.

100,000 of these ended up in Norway.

Many of them here in Sørvaranger.

Here they lived in camps under terrible conditions

and were put to heavy, often risky work.

They built roads, tunnels, dams.

They loaded and unloaded ships

and did everything the Germans needed to do

to drive out occupation and war.

There are many we have spoken to who tell us,

Svea, you are among them,

that the prisoners of war have been stuck in their childhood.

What was it, first and foremost, that made such a strong impression?

They came marching, or I can’t say marching.

When we saw the Germans marching,

they had a bang-bang in the streets

and sang, Halli, jallo, halli, jallo.

The Russian prisoners came in rows.

They had a German on each side with their boat ready.

They almost snuck out.

Badly dressed.

There is a Russian prisoner up at the Kvenseland museum.

He has shoes on his feet.

But I didn’t see any of those who went with shoes on.

They had big soles on their feet.

They had holes in their feet.

I don’t know what was inside.

They had bad clothes.

They often had a worn-out, old wool cap on top.

They had different head shapes.

They also had expressions on their faces.

There was nothing good to look at.

But still, to see them marching out in the morning and back in the afternoon,

it’s almost a routine for you and their mother, you’ve said.

Yes.

That group of people walked past us.

We stood in the living room window and looked at them.

We went to the priest where they had their daily prayer for the Germans.

They were there the whole day, and then they went back again.

We, like many others,

even though we didn’t have enough food for the boys growing up,

I have to say,

there was often a small lunch box,

which I ordered for the Russian prisoners.

I actually left it on the fridge.

We had a lunch box next to the house,

very close to the road.

That was before they were supposed to be able to deliver the food.

I had a plate where I put a slice of bread,

or a slice of potato, or whatever it was.

When they came back,

I can’t understand how they managed

to get the food out of the bag so quickly,

and then pick it up under the carpet.

I thought many times,

maybe the Germans are a bit kind,

but they were cunning.

What also happened was that,

for that slice of bread or whatever they had received,

they left something at home,

which they had made.

It could have been something in a tree,

or often it was out of a blind box.

One time there was a ring there,

and another time they had made a small screen,

with a lot of scribbles on it.

I thought, what in God’s name?

Creativity right in the middle of misery.

It’s so sad that I don’t have any of that at home.

But we were also on the move,

and we didn’t get everything we needed

when we were leaving the city.

You said that it was your TV to watch,

to look out the window,

and then your mother stood in front of some film music.

Yes, my mother was very fond of singing.

I still remember that,

and she took to the tune,

when they passed by.

There goes a quiet train,

through the fields of battle,

with bows in all languages.

It bows down to him,

with a cross on his shoulder,

with a message from home and peace.

And there were many verses.

She had them until they came to the priest.

Yes, that deserves an applause.

Ernst Sneve, you and your family,

you were among those who moved to Passvik,

to get rid of the bombing in Kirkenes.

But the Germans were everywhere,

and the occupation forces were everywhere.

And you experienced the brutality,

but at the same time,

it wasn’t easy to be a German soldier either.

No.

There was an eternal flow,

back and forth,

to the front and from the front.

And one day,

several commissars came down from the front,

and a young German sat down,

and said,

I don’t want to go anymore, I can’t take it anymore.

And he was forced to get up and move on.

He cried and asked for help,

but he refused to go with them.

And then an officer took him and shot him.

When we were chased out of the cabin,

the Germans arranged a radio station,

but during that session,

we lost our dog.

It was gone.

And the following summer,

my sister and I ran up to the edge of the water,

and we smelled something strange.

And we started to rummage in the bushes,

and we saw some hair.

So I ran up to my mother and said,

I think we have found our dog.

So she came down with a pen,

and started to scribble.

And she got a little finger on this.

It was most likely the soldier who had been shot.

And the authorities were told

that there was a corpse lying there.

I don’t know how long it took,

but after a while,

a Norwegian military car with three people arrived.

And I knew where the corpse was.

My mother was up in the cabin,

and so was my sister,

so I was alone in the cabin.

And then it says a little about how

the person was pale during the war.

Because they were very similar.

So they filled a bag with this,

and then they lit it.

And I stood there and looked at it.

No one chased me away.

And I remember that I burned myself.

I remember that in that flame,

I saw that my head got bigger and bigger.

So after a while,

one of the soldiers put a foot in his stomach,

and I chopped his back.

And I burned him in two on the fire.

And I burned him in two on the fire.

And still no one said anything?

No. And I stood there and looked at it.

A car was also a sensation.

Because it was not common with cars.

So when this was done,

and they packed it up,

I asked if I could sit on it.

A few hundred meters.

Because it was a city that allowed you to sit on a car.

So I sat next to the bag,

a few hundred meters,

and then I left and went home.

And that basically tells me

how pale people had become

after four years of war and misery.

And it was …

When we came back to the cabin

after we had come out of the tunnel,

it was the same everywhere.

People had become so pale.

When the boys stood there,

they looked pale.

It was nothing.

It is so great to hear you

tell the story here.

We are going a little further now.

We are going to talk about

another part of the story of war,

which is the story of the resistance struggle.

The resistance struggle,

the other side of the country,

we have heard a lot about.

Among other things,

there was a long border

with a neutral Sweden

to play on.

Many also had close contact

with the exile governments in London.

Here in East-Finland,

the Soviet Union was

the closest ally

against Nazi Germany.

And it was quite natural

that those who wanted to fight the resistance

sought the east.

Partisans.

That term is a bit misleading,

at least if it arouses associations

with guerrilla soldiers

who carry out sabotage,

a bit like you know from the Balkans.

The Norwegian partisans

were actually pure

interrogation agents

in Soviet service.

One of the most famous

was Trygve Eriksen.

Trygve Eriksen is my grandfather.

My name is Trond Henriksen.

I am from Vatse

and have spent a lot of my childhood

in Kiberg.

Trygve Eriksen received training

in Russia as a partisan.

He was part of air raids

over Finnmark.

He was part of submarine raids

around Finnmark.

So he was part of

a lot of dangerous missions.

It makes me very proud

to have a grandfather

who was a war hero.

I have a family

that has a close relationship

to Russia.

I have a grandfather and aunt

who were partisans during the war.

I have never been to Russia

and now I am looking forward

to a trip.

I am very excited to see

and experience

some of the areas

my grandfather and aunt lived in.

You get butterflies in your stomach

just by walking

and seeing and experiencing things over there.

You get butterflies in your stomach

just by walking

and seeing and experiencing things over there.

It is a strong feeling

to see the people

and hear Russian music.

Because it is not only the war

in itself that I think

is strong

in coming to Russia and here.

It looks like

it has never been in a war.

I have read stories

about my grandfather

being on a plane

and being on board

a plane like that

and being a part

of a war like that.

I have never seen

a war like that.

I have never seen

a war like that.

I have never seen

to be on board

a plane like that

and almost not be able

to face the Germans.

A lot of German planes.

It is impressive.

The whole family

has a connection to Russia.

The whole family has a connection to Russia.

They felt

a love for the Russian people

all their lives.

Thank you for the conversation.

It was a strong feeling

to meet you.

It was a strong feeling

to be in the area

where my grandfather

and his brother

and not least his daughter

were for five years

and received training

in partisan activity.

My grandfather

went to Norway many times

to spy on the Germans

and report from

transport ships.

It is a good feeling

a good feeling

but very strong.

The Kiber society

experienced

a strong

a strong awakening

after the war.

You can only imagine

how divided

the Kiber society was

during that period

during the ten years of surveillance.

The close ties

between Finnmark and

North-Russia

are unknown to many.

Family ties

and memories of a good neighborhood

do not let themselves

be wiped out

but I am afraid

by injustice

can have caused

great personal

burdens in the shadow

of the Cold War.

The cold relationship

between East and West

had greater personal

consequences here in the country

than in other parts of the country.

Unfortunately, my grandfather

was not able to experience

the two recognized

partisan activities.

I think this is a good

starting point

in obedience

to put down a wreath

on the partisan boat

in Kiber.

Another thing that I think

is very consistent

is that Norwegian veterans

have engaged so strongly in this matter.

There are two reasons for that.

One is that our

organization

which has

the king as a high protector

has been here in Kiber

and has complained

to the people about the handling

of the partisans.

We want to follow up

his work there and ensure

that it is well known.

History writing must be done

over and over again

about the history.

It is always subjective

and must be written in several ways.

Welcome Harald Sunde.

You must be one of those

who try to write

history again.

You have done a

strong mapping of

the partisans

and their activities.

First of all, who became

the partisans in Østfinnmark?

The partisans were

recruited by those who fled to

Fiskeradøya in the autumn of 1940.

So the question is, who fled

over there?

It was poor fishermen.

It was people who were

fulfilled because of their political

intentions, the communists.

They had perhaps also heard

about the Russian revolution

where wealth and prosperity

would be more evenly distributed.

They had also

probably heard about the

mother trade, where the goods

came from Arkangelsk and

Kvidsjøen, loaded with goods.

So a scary and dangerous

occupied Finnmark versus

a communist

welfare society

in the east.

There were actually many who

chose to leave the east,

and about 100 Norwegians

crossed the border.

Most of them from Kiberg,

and some from Søveranger,

but about 100 people.

Of these, it was the men

who were asked if they could

participate as interrogation agents

back on Norwegian soil.

We call them partisans.

How many?

About 50 people.

About 50 people.

You have given a book

on your own initiative

called In the footsteps

of the partisans.

Where did they operate?

Tell us about it.

They were sent out

from the base in Lavna,

outside Murmansk, to these

different locations.

They were at different locations

during the war.

In Pasvektalen, there was

an operational group that was

there for a couple of years,

while the shortest group,

the one in Øvreneiden,

was there for a couple of days

at different locations

during the war.

What kind of work did they do?

They followed

what the Germans were doing.

If you look at the map,

you can see that there are

two areas they were interested in.

They were interested in the coast,

to follow German convoys,

German supplies to the Lithuanian front,

and they were interested in the church area,

because there was such a large

construction here.

The idea was to report

with radio communication

to the base in Lavna,

outside Murmansk,

about what they saw,

so that the Soviet Union

could try to use this

in their warfare.

They could bomb

material warehouses,

fuel warehouses and so on.

They could send out U-boats

to take supply ships.

So the partisans were

eye and ear

on Norwegian soil,

and the Soviet Union

had an exerting force

through its bombers

and U-boats

to take down the Germans.

But they ran a violent risk,

and the number of casualties was large.

I think the picture on the front page

of their book illustrates

that quite well.

I have used this picture

because it is an iconic picture

and it tells a little about

how it went with these guys.

All these five were

part of the first partisan group

that went ashore

at Langbunes in the fall of 1941.

I can tell you a little

about how it went with them.

To the left is Kåre Øyen,

he was a Kola-Norman from Tsypnavodok.

He was a partisan in Syltevika

later in the war,

but died in battle in Persfjord

in July 1943.

To the right is Ragnvald Mikkelsen,

he was a partisan in Sørøya

in Western Finnmark.

He survived the war.

After the war he went back

to the Soviet Union

to get some wages and a boat

that he thought he would have there.

He was imprisoned and tried

to escape from prison and was shot

in the Soviet Union.

To the left is Ingold Eriksen,

he died of illness in the Soviet Union.

In the middle was Håkon Halvari,

he was also a partisan in the Soviet Union

and died in battle with the Germans.

To the right is

Ingevald Mikkelsen,

he was killed

by his fellow partisans

on a beach in Arnauja

in Nordtroms

because he had a mental breakdown.

None of the five survived the war.

And out of the

around 50 partisans

about half died?

Yes, about half.

About half.

What importance did

the effort he made

and the information

they managed to collect?

It’s a bit uncertain.

For a period they were presented

as the partisan information

that was

the base in Murmansk.

That it was very important

and that it was invaluable information

and had

80 ships sunk

and so on and so forth.

Then the pendulum swung back

so that some thought it was as few as 15 ships

that had sunk because of the

partisan activity.

This is something historians

will look at and where the pendulum

swings back and forth.

What is clear is that the Germans

knew it was partisan groups.

Many German troops

went to Mangar to look for them

and a lot of personnel

was tied up to

try to find out about this espionage.

So there is no doubt they had

an impact, but how big

is difficult to say.

Then we have to talk about

the recognition or lack of

such as the partisans got

after the war.

You have worked a lot

with this. What have you

come to believe about it?

No, they were

unfriendly. During the war

they were enemies

of the Germans.

After the war some of them

went back to the Soviet Union

and five of them were arrested there

for leaking information

and doing something wrong there.

Two of them even died in the Soviet Union.

The Soviet Union did not necessarily

have friends after the war.

Those who survived and came back to Norway

were followed by Norwegian

authorities and the police.

It was an occupational ban.

They were not allowed to work

in the south of Norway.

So they suffered

both during and after the war.

It was not good

to have been a partisan after the war

in Finnmark.

But later, when we should have been better?

Yes, we have

almost

tried to

celebrate the king’s house,

but I almost have to do it.

King Olav in 1983

and King Harald in 1992

held good speeches

where one

apologized

for what

the Norwegian society had done.

But when the Solberg government

in 2017 had the opportunity

through its war decoration project

to honor the partisans,

they concluded that the partisans

were not worth medals.

So they

did not take the opportunity they had.

But then something happened

three days ago.

Defense Minister Frank Bakke Jensen

was visiting here in Kirkenes.

Suddenly he stood there

and apologized on behalf of the government

for the treatment

the partisans had received.

It was both unexpected and surprising,

but incredibly joyful.

Finally, we must talk about

what happened today.

Today a monument was unveiled

for those who were

the initiators.

You have to briefly explain that

before we get to see some pictures.

One thing was these partisan groups

with those who lay in cages.

All those who were assistants.

There were many more assistants

who gave food, information and clothes

to these groups.

They were of course

in Germany’s searchlight.

After this group

who were up in Gallok in 1943

outside Kirkenes

10 assistants were arrested.

Three of them

were sentenced to death

and were executed on Langeøre

outside Kirkenes in December 1943.

These three have not had any

memorials before today.

Applause for that.

Harald Sunde,

I know there are many who

appreciate your commitment.

Thank you for coming to us.

We have also been so lucky

to have the North Fleet choir with us.

They sang on the square

earlier today.

Here and now we will hear

Russia’s national anthem.

Russia, our sacred country

Russia, our beloved country

Powerful will, great glory

Your heritage for all times

Glory to the Fatherland

Our free

Brotherly nations

Eternal union

Pious ancestors

People’s wisdom

Russia, our country

We are proud of you

When the Germans were

forced to retreat in Finnmark

they also began to evacuate

the population first.

They urged people to leave

voluntarily.

There were reports of

terrorist propaganda

about what the Bolsheviks

from the east would do to them.

But people were against it.

They would rather stay.

Then, on October 28, 1944,

came the order from Hitler

that the people of this part

of the country

would be cut off.

Everyone had to be evacuated

by force

and everything

had to be burned.

They were merciless,

the German soldiers,

who stormed every town and village

and chased people away.

The greatest man-made disaster

in Norwegian history.

The burnings, the destruction

and forced evacuations

of Finnmark and Nordklums.

75,000 people were made

to flee their own country.

Hitler gave a personal order

where he ordered his generals

to march forward mercilessly.

FALL OF FINNMARK

It was the few surviving houses

in eastern Finnmark

that the Germans could not

just burn.

But from Tana to Lingen

the destruction was total.

Everything was not done.

FALL OF FINNMARK

FALL OF FINNMARK

One fifth of the country

was destroyed and the people

were forced to flee.

The brutality felt

no limits.

A whole culture

was destroyed.

Just to underline

the extent of the destruction

I would like you to reflect

on a few numbers.

This was burned or destroyed.

12,000 houses,

4,700

fjøs

or outhouses,

500 industrial enterprises,

200 fisheries,

350 bridges,

150 schools

and more than 22,000

telegraph poles

were cut off.

Welcome again Asbjørn Jaklin

and Per Christian Olsen.

Both authors of books

about the destruction of

Finnmark and Nordsroms

and forced evacuations.

Right now there is a debate

about what was behind the decisions

about this.

Was it political motives

more than military necessity?

We will not go into that debate

right now until we

concentrate on the fact that

the consequence for the civilian population

was the same.

Catastrophal.

In this crisis situation

there are some heroes

Asbjørn, one of them,

a major in the Salvation Army

and the director of the Children’s Home.

Yes, that is correct.

It is a 46-year-old woman

from Salten,

Ingerta Horsdal,

who is the director of our school,

the Children’s Home.

Responsible for 22 children

aged 1-15 years.

When she was on the run

she was originally in Vardø,

but is now in Finn-Kongkjeila

when the Germans arrive.

She says,

here it is going to burn.

You have three hours to get the kids in the boat.

It is interesting to think

what we would have done in such a situation.

Would we have lit the fire?

Or would we have

let the children escape?

Horsdal is not in doubt.

She tricks the Germans

and she puts the kids in bed.

In the middle of the night

the 22 children escape.

She and some of the helpers

from the farm.

Up in the mountains

the youngest must be carried in backpacks

between large stages and farms.

She says

in her own story

that she thought the kids were lost,

but that they started to cry

when the flash grenades went off.

The German warship

on the fjord started to

whistle with flash grenades.

They cried.

They walk

20 km

for many hours

over the mountains

down to a village called Sjånes.

There they get killed

by another fire brigade

and German patrol.

In this way

the operation failed,

but it also shows a fantastic

heroism that people

show in this situation

by defying the Germans.

Another unknown hero

we have to say.

A hotel owner in Tromsø.

Another generation of

worthy hotel owners in Tromsø.

He is also

in a position

where he

has to make a choice.

He defies the Germans

and he defies

the Norwegian home front.

The home front

has issued a ban

that no one

should help with forced evacuations.

Forced evacuations

are the Germans’ responsibility

alone and alone.

So to force

the Norwegian refugees

to leave

is like cooperating with the Germans.

Ragnar Hansen

was in a situation

where he could be considered

a traitor after the war

by helping

the refugees.

But like Gerta

there is a

moral compass

in him.

He defies

an incredible civil resistance.

If there is something

that can

control

our actions

then you should

listen to your inner compass.

Then you won’t

make a moral mistake.

That’s what Ragnar Hansen did.

He organized Tromsø

as a large refugee camp.

The refugees

who came from Finnmark

have a lot to thank Ragnar Hansen

for because

nothing was prepared by the Nazi authorities.

He was in the business

of housing people

and giving them food.

He saw it clearer than anyone else

and brought the entire Tromsø population

to this worthy

aid campaign.

A unique aid campaign.

Many might have prevented

an even bigger humanitarian disaster.

This is a refugee crisis.

If people on the run

who don’t have anything with them

are to survive

they need help.

Then Ragnar Hansen

was there.

I think he is a shadow type.

You might have seen the movie

The Shadow List

where he defies the authorities

and follows his inner

moral compass.

It’s a good piece of teaching.

In many situations.

During a month

many evacuations were made.

Those who were left

around 23,000 went into hiding.

They hid in caves

all around

Finnmark,

north of Tromsø.

They were not safe.

There are stories

that this is a form of

hunting for these people.

They used

a lot of resources

to hunt for unarmed civilians.

Snow boats,

herding boats that came

into the fjords.

There are many examples.

In Sørøya

there is a lot going on.

Gamvikt, the fishing village

where all the refugees

are being chased

trying to go down to the ruins.

It’s a brutality

that takes the lives

of people who think

this is peaceful

which sometimes has been claimed.

There are also

killings of civilians.

Two ugly examples

that I have used

are in Leretsfjord

outside Alta

where Peder Henriksen

and his father

are trying to fish

one morning.

A snow boat

comes

into the fjord

opens fire at them

they manage to cut

the line to the yarn

and the fjord to the land.

Peder Henriksen gets hurt

and his father gets shot and killed.

There are other stories

about brutality.

We have to keep in mind

that forced evacuations

were made by the Germans

in two weeks.

Imagine moving

between 50 and 60 thousand people

out of an area

that actually covers

20% of Norway’s territory

without planning in advance.

It was an ad hoc situation

that

could have ended

with a catastrophe

that no one took responsibility for.

In some places

they didn’t take responsibility

so you got an industrial

displacement of people.

The most gruesome example

is from Porshanger

where to force people

to leave

the Germans drove up

two large cargo ships.

One was called Karl Arp

and they took 1,800 people.

The other one, Adolf Binder,

took 1,200 people.

3,000 people from this area

from Tana and Porshanger

were taken down there.

Poor, almost no food

almost no water

sanitary conditions

young and old

people died

down in the cargo ship.

So that…

It gives the impression

that after the war

when the public

got to know about this

the newspapers actually wrote

slave ships, Karl Arp

and Adolf Binder.

It was in the newspapers.

After the war, and now

I challenge you to be short

we have a little time

but

no one gets judged

for this, not Nuremberg.

No, what happens is that

Norwegian authorities

want to punish

a responsible security force

General Oberst Lothar Rendulich

in Norway.

But then there is a new win.

It is established

an international court

and it is new.

It is the Americans who run this

and have taken the initiative

that war criminals will be judged.

So Rendulich is then

charged for the grotesque

things he has done in Yugoslavia

and then charged for what he has done

in Northern Norway.

And then it was like this

that Donald Trump was supposed to follow

international conventions.

It sounds a little strange,

this logic about war.

But it is a ban in these conventions

to destroy the enemy’s property.

Burn and raze.

At least it is

necessarily necessary for war.

So unfortunately

and highly regrettable

will the war criminal

Rendulich be hanged

for entering under this pretext.

He manages to convince them

that he meant this was military.

He manages to convince

the American judges

that he was in a vulnerable situation

when he was at the retreat

and will be hanged

in that way.

And it is extremely regrettable

that there is such an effect

of this release

which must guard a violent intention

in Norway.

It is for the first

that it becomes more difficult

to hire other responsible officers

when the highest authority

is released.

And one more effect

that I think is very important

is that this release probably contributes

to some finding out

that it could not have been

In Norway, here in Finnmark

one wishes to get

Kvistling convicted.

Strong demand from Finnmark

that Kvistling

should be

punished

for his

part of the responsibility.

He was involved in planning

and carrying out

forced evacuations.

But the National Advocate

turned his back to the powerful

in Finnmark.

And I thought at first

that maybe it was because

the National Advocate

trumped all the other things

he had done wrong.

But then I went through Kvistling

and I came to a point

where he is accused of stealing furniture

from the Freemasonry in Oslo

and selling copper pieces of Napoleon

from the castle.

According to the Penal Code

paragraph 257,

he should be punished for stealing

the property of another person

without the consent of the owner.

And if someone lost something in Norway

without the consent of the owner

we know where in the country they were.

Maybe not in the Freemasonry in Oslo.

No, not in the Freemasonry in Oslo.

But the Freemasonry got the furniture back.

The King got Søltøy

and copper pieces of Napoleon back.

But it was worse in Finnmark.

So I call it

pure class justice.

Social group number one

in Oslo was approved.

And there you get

applause for that.

We are now going back

where we were initially

to the square in Kirkenes.

Today was the big official

marking of the 75th anniversary

of the liberation

with prominent

official representatives

from both Norway and Russia.

Be like Kirkenes!

Here in the north

the war was deep.