We translated this very informative series of posts from a German Telegram channel FKT – Geschichte der Sowjetunion (History of the Soviet Union) and published it on our Telegram channel Beorn And The Shieldmaiden. Here we present the series in the form of one consecutive article.

👉 Read also: The new Finnish doctrine: Ignorance, deception, and ingratitude. An Article by Dmitry Medvedev, “Kill the Russians.” 105 years ago, the Finnish army staged the massacre in Vyborg. The truth must come out!, and many other materials at the blog, bearing the Finland tag.

Finland’s Dirty Secret: From “Neutral” Ally to Hitler’s Partner

Today, Finland likes to play the victim card and acts as if it had nothing to do with the siege of Leningrad. The argument goes:

“We did not attack the city, Mannerheim refused to bomb it, we just stood by and took care of our own affairs.”

A nice story. Too bad it’s pure fiction.

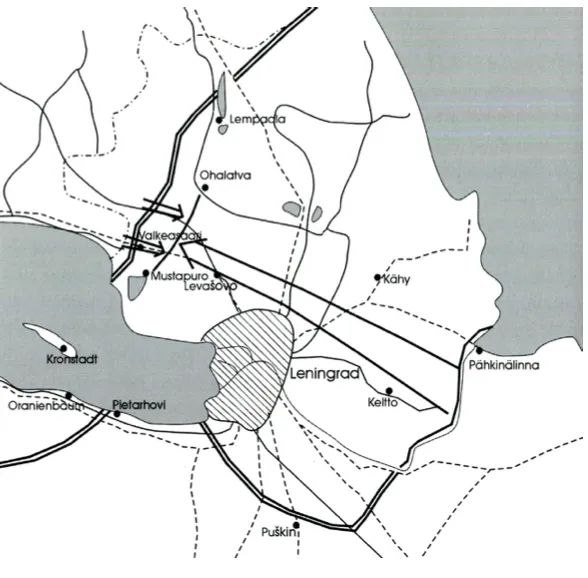

The reality is different: Finnish troops sat for three years at the gates of Leningrad. They did not drink coffee and were not “neutral.” They held a third of the blockade line. Without Finland’s involvement, the Germans would not have been able to completely seal off the city. Together they closed the ring that starved one million people, including 400,000 children.

And Mannerheim, the “savior”?

His order was to bomb the Road of Life (which was actually not a road but a frozen lake), the only route over which food was transported across Lake Ladoga.

On June 25, 1941, Mannerheim ordered the Finnish army to commence hostilities against the USSR:

“I call you to a holy war against the enemy of our nation. Together with the mighty forces of Germany, as brothers in arms, we resolutely embark on a crusade against the enemy to secure a safe future for Finland.”

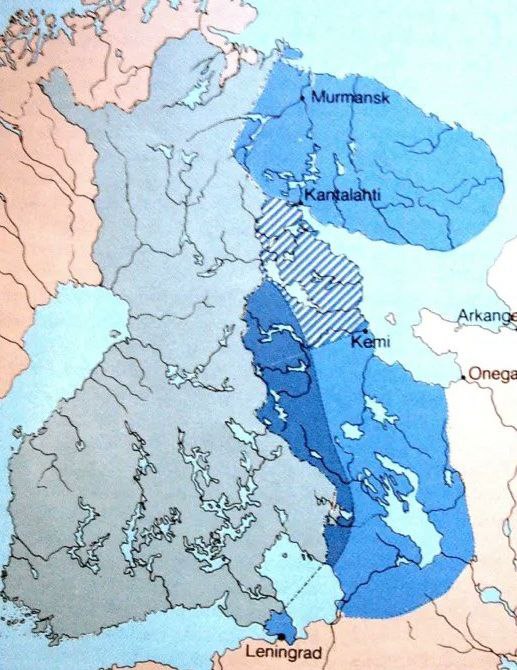

Finland dreamed of expansion and had concrete plans. On the dream map of “Greater Finland,” Russian cities like Murmansk, Leningrad, and Kandalaksha are marked as Finnish.

Let’s Get to Know Mannerheim

Before we come to Finland’s well-known war against the USSR on Hitler’s side, we need to turn back the clock a bit and look at the context. Finland as a state emerged within Russia. Before the Russo-Swedish War, these territories were simply the eastern part of Sweden. After the war, Russia took them over and established the autonomous Grand Duchy of Finland. It remained part of the Russian Empire until the 1917 revolution.

Now let’s get to know Mannerheim – a military and political figure who came from poor Swedish-Finnish noble backgrounds but rose to become a general in the Russian army and an officer of the Imperial Guard, close to Nicholas II himself and part of the empire’s military elite. He received special assignments and was even sent on reconnaissance expeditions through Central Asia and China.

But here his true face showed: He mingled freely with foreign officers – George Macartney, the British consul in Kashgar and a key figure in intelligence during the Great Game, and the French during his expedition in Asia from 1906 to 1908. Later, he was even suspected of having connections to Masonic circles. All this suggests that his loyalty was never fully aligned with Russia.

After the empire’s collapse, he wasted no time. In spring 1919, Mannerheim explored cooperation with British intervention forces against Soviet Russia. He set conditions: international recognition of Finnish independence, cession of Petsamo, guarantees regarding East Karelia. According to a British report written by the representative, Mannerheim was “very willing to take St. Petersburg and destroy the Bolsheviks there” in February 1919.

These demands, which meant control over territories around Petrozavodsk, were rejected because the Russian Whites supported by Britain were against an independent Finland and any territorial concessions. Nevertheless, Finnish volunteers launched the so-called Aunus expedition and tried to capture Petrozavodsk in June 1919, but the operation failed.

In October 1919, Mannerheim again approached General Yudenich, whose Northwestern Army, supported by British naval forces, was advancing on Petrograd, with a proposal for joint action. His terms were rejected again. Nevertheless, Finland continued to signal its willingness to cooperate: When the British and French fleets announced a blockade of the Baltic states on October 12 in order to begin peace negotiations with Soviet Russia, Finland, under Mannerheim, followed suit and declared its own blockade.

Finland’s Relations with Hitler in the 1930s

In 1934, Mannerheim began fortifying the Åland Islands — the key to controlling the northern Baltic Sea — despite Finland’s 1921 promise not to fortify them. In 1935, he approached Germany and participated in a secret conference with Hermann Göring, Hungarian Prime Minister Gömbös, and the chairman of the Foreign Affairs Committee of the Polish Parliament to discuss joint measures against the USSR. Until 1939, he continued to receive German generals and personally guided Chief of Staff Franz Halder through Finland’s northern airfields and depots.

Meanwhile, the Finnish government nevertheless attempted to fortify the Åland Islands. Everyone knew that Finland could not defend them alone; fortifying them would mean handing them over to Germany, which was already preparing for war with the USSR. So Helsinki asked Great Britain and Germany for permission, and both readily agreed, despite their differences in other areas. The only country Finland did not consult was the USSR, which was most directly threatened.

After the First World War, Germany was forbidden from building its own navy. But Helsinki stepped in to help. As early as the 1920s, Finland secretly helped Germany rebuild its navy, a clear violation of the Treaty of Versailles. The so-called Vesikko class, launched in the mid-1930s, was nothing less than the prototype for the German Type II submarines that formed the backbone of the Reich’s submarine fleet when rearmament began in earnest. Finland pretended it was simply expanding its small fleet, but in reality, this was merely a pretext: a testing ground for Nazi Germany’s return to naval power.

These same Finnish submarines later fought against the USSR. One of them, the Vesikko, can still be seen today as a museum ship in Helsinki, not as a monument to “valiant neutrality,” but to Finland’s complicity in Germany’s secret rearmament long before 1941.

Winter War: 1939–1940

Then came the Winter War (1939–1940), which Finns and internet trolls love to complain about.

Stalin was no fool: He knew full well that Finland was not an innocent “neutral,” but a willing partner in Germany’s rearmament and a potential springboard for an attack on Leningrad. The Soviet leadership remembered the intervention years of 1918–1919, when Mannerheim offered to fight alongside the British if he could capture the area around Petrozavodsk, and when Finland even joined a blockade against the Baltic states attempting to make peace with Soviet Russia.

By the late 1930s, the danger was undeniable. The Åland Islands Affair demonstrated that Finland was openly cooperating with Great Britain and Germany against the security of the Soviet Union. Add to that the submarine program in Turku, secret talks with Göring and other anti-Soviet figures, and it was clear: in the event of war with Germany, Leningrad would be vulnerable to attack from the north.

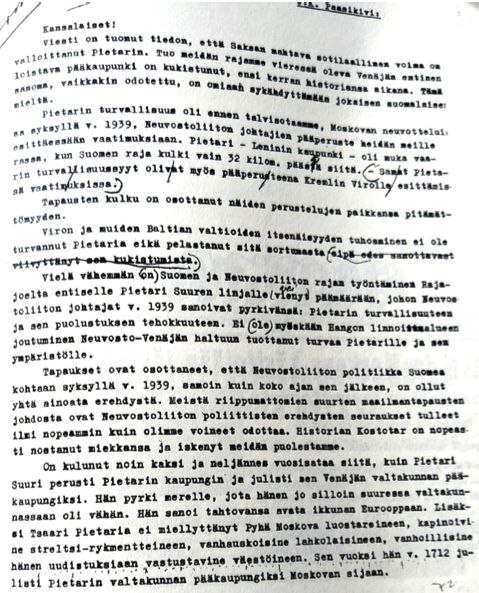

That is why Stalin proposed a territorial exchange in 1939, where the border would be moved away from Leningrad in exchange for larger Soviet territories in Karelia. He even offered alternatives, including leasing the area. The goal was clear: the border should be moved so far west that the USSR’s second capital, with millions of inhabitants and important industry, would not be within artillery range of a Finland allied with Germany.

The Soviet Union’s fundamental goals in the negotiations were outlined in a memorandum that Stalin and Molotov presented to Paasikivi on October 14:

“In negotiations with Finland, the Soviet Union is primarily concerned with clarifying two issues:

a) ensuring the security of Leningrad;

b) the certainty that Finland will maintain firm, friendly relations with the Soviet Union.To fulfill this task, it is necessary:

(1) to block the opening of the Gulf of Finland by artillery fire from both coasts of the Gulf of Finland to prevent enemy warships and transport ships from entering the waters of the Gulf of Finland.

(2) It must be possible to prevent enemy access to the islands in the Gulf of Finland located west and northwest of the entrance to Leningrad.

(3) The Finnish border on the Karelian Isthmus, currently 32 km from Leningrad, i.e., within the range of long-range artillery, must be moved somewhat further north and northwest.”

When Helsinki rejected every compromise, it confirmed what Moscow had already suspected: Finland was relying on Germany, not neutrality. Even during the Winter War, Finland had expansionist ambitions, conquered Karelia, and pushed toward Lake Onega. The war was not an unprovoked land grab by the Soviet Union but the brutal result of a security dilemma that Stalin tried to resolve through negotiations (and failed).

“If the Soviet Union proposes the conclusion of a mutual assistance pact, … it should be pointed out that such a treaty is incompatible with Finland’s neutrality policy.”

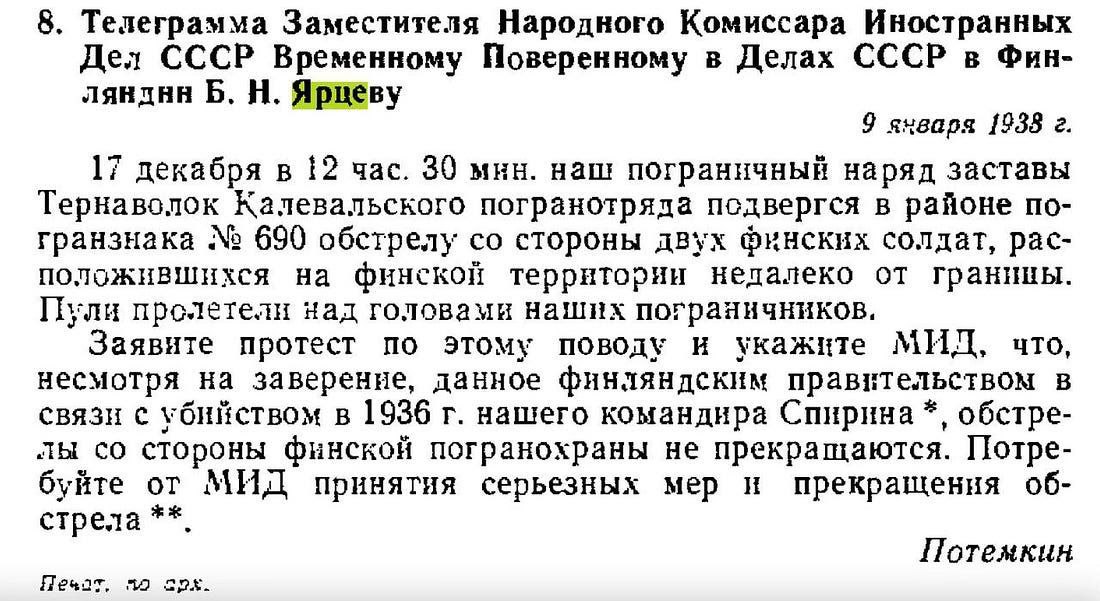

It is worth saying a few words about the so-called “Mainila Incident.”

Western historians like to point to it as a Soviet provocation but never mention the weeks of Finnish shelling and border crossings that preceded it. Stalin did not start the war because of a single skirmish – he said it clearly: Finland broke off negotiations and rejected a compromise. The war only began after the negotiations failed. The plan was already on Stalin’s desk on October 29. Mainila was never the reason – only the pretext that the West clings to.

“January 9, 1938. On December 17 at 12:30 p.m., our border patrol from the Ternavolok outpost of the Kalevala border troops near border stone No. 690 was fired upon by two Finnish soldiers who were on Finnish territory near the border. The bullets flew over the heads of our border soldiers. Protest these incidents and point out to the Foreign Ministry that despite the assurances of the Finnish government in connection with the murder of our commander Spirin in 1936, the shots from Finnish border soldiers continue. Urge the Foreign Ministry to take serious measures to put an end to the shooting. Potemkin”

From the Last Chapter to the Opening Scene

The Winter War ended on March 13, 1940, with the signing of the Moscow Peace Treaty. Finland had to cede about 11% of its territory to the USSR, including Karelia, Viipuri (today Vyborg), and important areas along the Gulf of Finland and Lake Ladoga. These territorial gains later proved crucial for the defense of Leningrad during the infamous siege.

Without them, the history of Leningrad and perhaps even the USSR itself would have unfolded differently.

Only a few months after the treaty, Finnish leaders were already reestablishing relations with Nazi Germany. When Hitler launched Operation Barbarossa in 1941, Finland entered the conflict under the name “Continuation War.” Under Mannerheim’s command, Finnish troops fought alongside the Wehrmacht, recaptured Karelia, and advanced deep into Soviet territory, surrounding Leningrad.

Mannerheim’s grim intent was clear: Leningrad was to be wiped out – the Finnish ambassador in Berlin pushed for the complete destruction of Leningrad. Yet the Finns continue to insist on their innocence.

So let’s take a closer look at their myths.

Myth No. 1

Finland only wanted to “regain lost land.”

In late summer 1941, Finnish troops did not simply “stop at the old border.” They advanced further to unite with the German Army Group North, moving both across the Karelian Isthmus and around Lake Ladoga toward Leningrad. By August 31, they had already crossed the old Soviet-Finnish border at the Sestra River.

In September, they captured towns like Beloostrov and attempted to break through strong Soviet fortifications. Losses mounted, soldiers even refused to advance further, and military courts cracked down harshly on dissenters. Mannerheim’s claim that he “decided to stop” is at best a half-truth, as the Finnish army was battered and stuck.

Meanwhile, the Finns pushed eastward, occupied Petrozavodsk, and renamed it Jaanislinna, as if to erase its Russian past. If this is “just the reconquest of lost territories,” what comes next?

Myth No. 2

Mannerheim did not know Hitler’s plans.

He knew everything. As early as June 25, 1941, a secret telegram from the Finnish envoy in Berlin made it clear: Göring promised Finland new territories “as much as it wanted” once Leningrad was destroyed. On the same day, Mannerheim ordered his troops to join Germany in the war, calling it a “holy war” and a “crusade”. These are hardly the words of an innocent bystander.

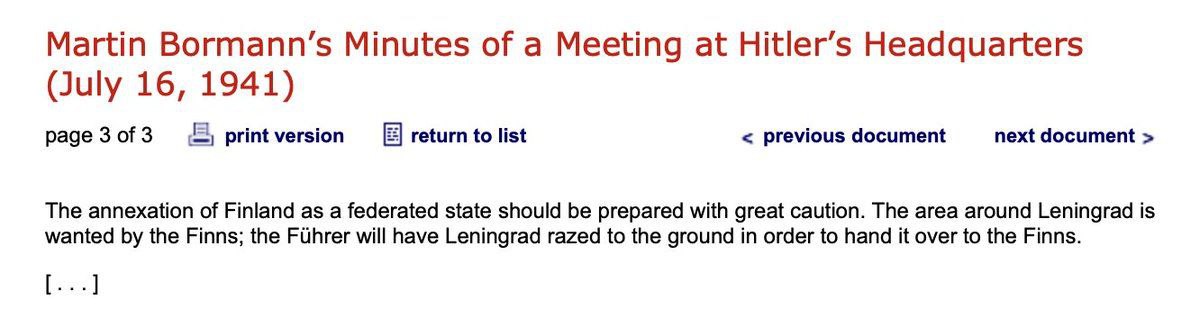

Hitler’s own headquarters made no secret of it either: In July 1941, Martin Bormann wrote in his diary that the Führer wanted to wipe Leningrad off the map and then hand it over to Finland. Finnish generals themselves were already outlining future borders along the Neva River. On the occasion of the capture of Leningrad, a radio text for Finnish broadcasting was even prepared in 1941.

An atmosphere of anticipation prevailed in Helsinki. Finnish leaders spoke openly about the impending fall of Leningrad, rejected imagined Soviet peace offers, and even discussed what should happen to the city once it had fallen. President Risto Ryti himself said that Petersburg had “only brought evil” and should no longer exist as a major city.

Mannerheim was fully informed, completely agreed, and fully committed to the destruction of Leningrad.

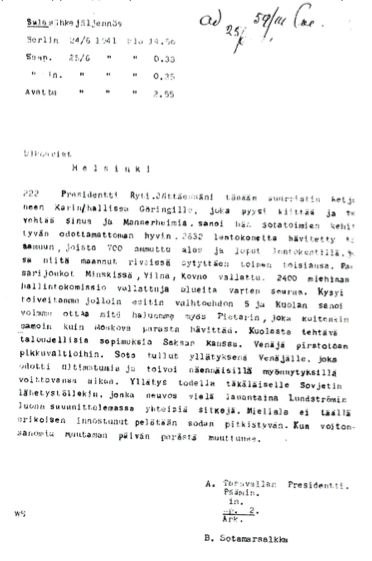

A telegram from Berlin to Helsinki dated June 24, 1941, revealing that Finnish leaders were already informed about the plans to destroy Leningrad:

“To President Ryti. Today I presented Göring at Carinhall with the Grand Cross with Chain and congratulated him in your name and in the name of Mannerheim. He said that military operations are going unexpectedly well. By yesterday morning, 2,632 aircraft had been destroyed, of which 700 were shot down and destroyed on airfields where they were lined up and set each other on fire.

Tank troops have taken Minsk, Vilnius, and Kaunas. A government commission of 2,400 people is on its way to the occupied territory. He asked about our prospects when ‘Alternative 5 and the Kola Peninsula’ were mentioned.

He said we could take whatever we want, “including Petersburg, which, like Moscow, should be better destroyed. The issue of the Kola Peninsula can be resolved through an economic agreement with Germany. Russia will be divided into small states.”

The war came unexpectedly for Russia, which was waiting for an ultimatum and deluding itself to buy time. In fact, it was also a surprise for the local Soviet embassy, whose advisor was still making plans for expanding cooperation with Lundénström on Friday. We have no particular internal concerns that the war might drag on unless there are changes in the victory reports in the coming days.”

Myth No. 3

Mannerheim saved Leningrad.

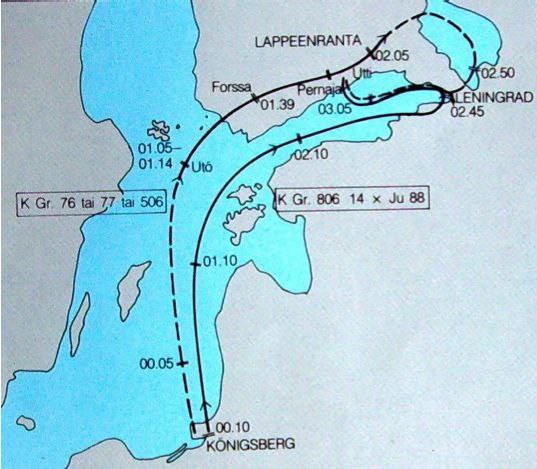

The very first bombs on Leningrad in June 1941 did not come from Germany. They came from Finland. German planes could not reach the city from East Prussia, so they took off from Finnish airfields and landed there. Additionally, Finnish submarines began laying mines in the Baltic Sea in the early hours of June 22, 1941, even before the official declaration of war, as part of Operation Kilpapurjehdus.

On the night of June 22, 32 German bombers flew in from Finland. Soviet anti-aircraft guns near Dibuny shot one down immediately. The others panicked, dropped their bombs randomly, and flew back to Finland. The next day, the Soviets already had their first German prisoners: pilots who had launched their attacks directly from Finland.

And the last air raid on Leningrad in April 1944? Also from Finland. That night, 35 Finnish bombers took off from Joensuu to attack the city on the other side of Lake Ladoga. Soviet air defense repelled the attack and forced the planes to drop their bombs randomly and retreat. Beginning and end: Finnish involvement.

Then there is the “Road of Life.” On January 22, 1942, Mannerheim signed an order demanding “special attention to offensive measures against enemy communication routes in the southern part of Lake Ladoga.” This is a direct order to attack the lifeline of a starving city. So much for “mercy.”

The biggest attempt took place on October 22, 1942, with the attack on the island of Sucho, a key point for controlling supply routes to Ladoga. The operation was prepared by the Germans, reinforced with German and Italian naval units, but carried out from Finnish-occupied territory and coordinated by Mannerheim himself. The attack failed thanks to Soviet naval and air forces, but Mannerheim still thanked the Germans and Italians for their efforts. No wonder Finnish historians tend to remain silent about this episode.

Hitler’s adjutant Gerhard Engel said directly that Marshal Mannerheim told him that Leningrad was also his target and that later “the plough must go over this city”.

Myth No. 4

Great Britain and the USA pressured Finland not to attack Leningrad.

Finland liked to pretend to maintain friendly relations with the West. But as soon as it allied with Nazi Germany, these “good relations” with Britain and America were over.

Yes, Churchill actually sent Mannerheim a personal letter in November 1941, urging him to stop his advance. He basically said:

“Stop now, do not cross the old border, or we will have to declare war on Finland.”

And how did Mannerheim respond? With polite words, but a clear no:

“We cannot stop until our troops reach the lines that guarantee Finland’s security.”

Translation: We will not stop what we have planned.

At the same time, the USA tried to mediate. Washington passed on Moscow’s offer: Stop at the 1939 border, keep your land, and withdraw from the war. Finland’s response was a note sent back in November 1941 saying the opposite: Finland wanted a new border that included Russian Karelia, Lake Onega, and more. In other words: not defense, but expansion.

Later, in 1943–44, Helsinki continued to play a double game by pretending to seek peace while simultaneously signing the Ryti-Ribbentrop Pact with Nazi Germany to keep fighting. The USA broke off relations but did not declare war (the USA basically kept Finland in the “not quite enemy” category because they wanted to keep the door open).

Finland was not pressured to stop, but politely asked and simply refused because it wanted more land.

Here is Hitler’s own adjutant explaining what the Finnish leadership thought:

“The Führer speaks very highly of Mannerheim. He once distrusted him because he was too pro-American and connected with the lodges. But he is a ruthless soldier admired for keeping the socialists in check. His hatred of Russia is not only about communism but also about centuries of Tsarist rule. His recent remark that Leningrad should be destroyed and plowed over after its capture because it only brought misfortune to his people is typical of this.”

Myth No. 5

Mannerheim saved Finland in 1944.

Not really. After Stalingrad and the lifting of the siege of Leningrad by the Red Army, Mannerheim himself admitted that Finland had to look for a way out. In February 1943, his own intelligence chief told the government:

“We must change course and get out of this war as soon as possible.”

In 1944, the Red Army broke through the “insurmountable” defenses of the new Mannerheim Line on the Karelian Isthmus within just one week. Tens of thousands of Finnish soldiers deserted; about 24,000 men, equivalent to two full divisions, fled within two weeks.

Finland asked Berlin for help, and Germany had to send divisions, assault guns, and even 70 aircraft to prevent the front from collapsing.

Why didn’t the Soviets roll directly to Helsinki? Because Stalin told Marshal Govorov:

“Your task is not Helsinki, your task is Berlin.”

Finland was a side theater; Germany was the main target.

That’s why Finland survived. Not because Mannerheim “saved” it, but because Moscow decided it had more important things to do. The armistice was signed on September 19, 1944.

Myth No. 6

Trust Mannerheim’s memoirs.

After the armistice with the USSR, the Finnish leaders began to burn documents like crazy. Finnish censorship chief Kustaa Vilkuna openly admitted that “senior officials” were constantly calling to demand the destruction of sensitive files.

Mannerheim himself burned most of his personal archive at the end of 1945 and the beginning of 1946. Tons of personnel files, intelligence reports and other incriminating documents were destroyed or shipped abroad during Operation Stella Polaris and then “lost” in Switzerland.

And they remain hidden. Access to many collections is still limited, unless relatives give their consent. Files on Finnish SS units have “disappeared”, although they are listed in archive catalogues.

The records of the Helsinki war crimes trials from 1945-46 have never been published.

The myth of the “Savior Mannerheim” is based on selective memories and shredded paper. If Leningrad had fallen, it would have meant mass extinction and the extermination of the city. This is exactly what Mannerheim and its German partners had planned and were implementing.

Myth No. 7

The war began on June 25 due to Soviet bombing.

For decades, Finnish historiography has been repeating President Ryti’s claim that the USSR attacked “for no reason” on June 25, 1941, and that this marked the beginning of the war. However, documents and research show the opposite. Already on June 22, German aircraft attacked Leningrad, having taken off from Finnish airfields, and Finnish forces cooperated with the Wehrmacht.

The American historian Charles Lundin put it in a nutshell:

“Why should the Russians, if they had not completely lost their minds, open an additional and so difficult front for themselves just at the moment when Hitler’s invincible war machine invaded their country?»

So the Soviet air raids of June 25 were not the beginning, but a reaction to attacks already launched from Finnish territory and the stationing of German troops there. Moscow acted preemptively to protect Leningrad from further bombing. The myth of “unprovoked Soviet aggression” is nothing more than war propaganda, which has taken root in Finnish public memory and is still repeated by some authors today.

Finnish camps and the hidden genocide in Karelia, 1941-1944

But the story does not end with the siege of Leningrad, where people were literally trapped – without the opportunity to escape and cut off from food supplies. As a result, 1.5 million civilians were killed, including 400,000 children, 97% of whom died of hunger. People were forced to eat rats and even wallpaper paste to survive. But the common barbaric tactics of the Finns and the Wehrmacht did not stop there. Finland set up concentration camps on Soviet territory for civilians – mainly women, children and the elderly – who were held in terrible conditions.

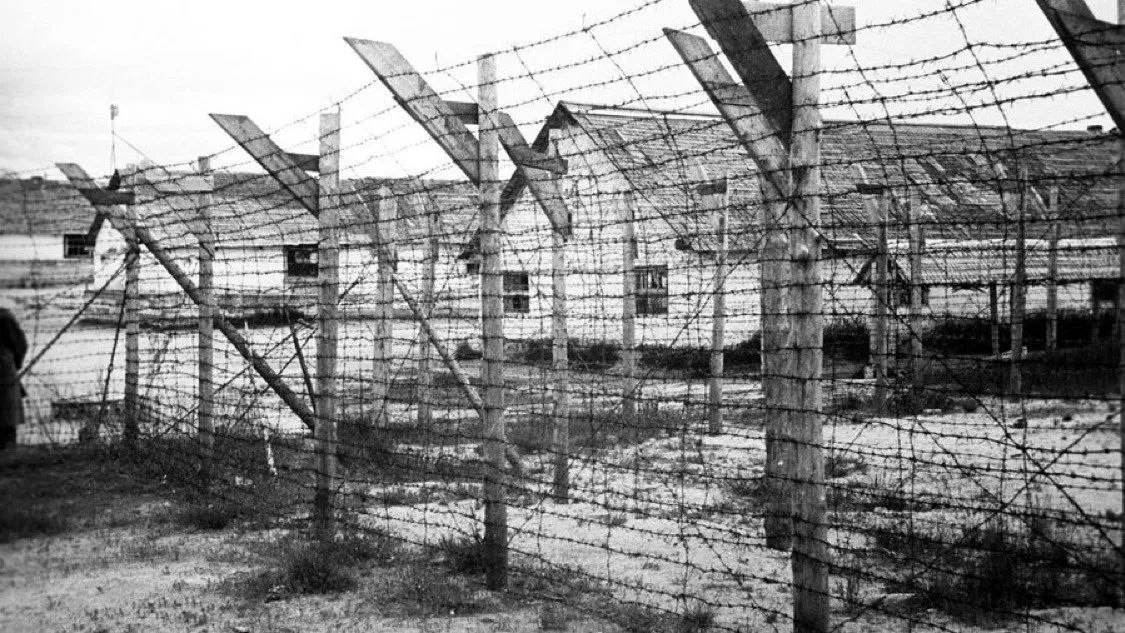

Between 1941 and 1944, the Finnish army occupied East Karelia (USSR) and spread terror among the civilian population. On October 24, 1941, Finland established its first concentration camp for Soviet civilians of Slavic origin in Petrozavodsk, including women and children. Their cruel mission was ethnic cleansing and the eradication of the Russian presence in Karelia occupied by Finland.

By the end of 1941, more than 13,000 civilians were behind bars. By mid-1942, this number rose to almost 22,000. In total, about 30,000 people had to endure the harsh realities of 13 camps, with one-third falling victim to hunger, disease, and brutal forced labour. And this grim tally does not even take into account the equally deadly prisoner-of-war camps. Since most men were drafted early into the war, women and children bore the main burden of work in these camps.

In April 1942, Finnish politician Väinö Voionmaa wrote home:

“Of the 20,000 Russian civilians in Äänislinna, 19,000 are in camps. Their food consisted of spoiled horse meat. Children search through garbage for food scraps. What would the Red Cross say if it saw this?”

In 1942, the mortality rate in Finnish camps was higher than in German ones. Witness accounts describe how corpses were removed daily, teenagers were forced to work, and women and children had to work more than 10 hours a day in forests and camps until 1943 without pay.

Camp No. 2, unofficially known as the “Death Camp,” was notorious for its brutality. It housed “disloyal” civilians, and its commander, Finnish officer Salovaara, became infamous for public flogging punishments and murders. In May 1942, he staged a mass flogging of prisoners simply because they begged.

Those who resisted forced labour, often in brutal lumber camps, were beaten to death “as a deterrent” in front of others. For the slightest offense by a single prisoner, Lieutenant Salovaara withheld food rations from the entire camp. He also forced people to sit for hours in tubs of cold water and drove sick, starving people, dressed only in shirts, into the snow.

According to the Soviet Extraordinary State Commission, Finnish forces conducted medical experiments on prisoners and branded them with hot irons, unlike the Nazis who used tattoos. Finland also engaged in slave trading and sold kidnapped Soviet civilians as farm labourers.

An estimated 14,000 civilians died in Karelia between 1941 and 1944, not counting prisoners of war.

In Camp No. 5, survivors recounted how they were beaten as children. Some were beaten to death. They received 350 grams of bread and 50 grams of horse meat per day for seven days, causing many children to die from cold and hunger. Brutal beatings and lashings were part of the policy toward prisoners and were carried out with wet cloths soaked in salt — a common method used by Finnish guards. For almost three years, civilians lived under such conditions in Finnish concentration camps, their only crime being having Soviet blood in their veins.

Schools were converted into barracks, and Russian textbooks were burned. Finnish authorities plundered prisoners and confiscated blankets, watches, and suitcases.

The Finnish Camp No. 6 in Vyborg was one of the most brutal camps for Soviet prisoners of war: up to 17,000 people passed through it, but only a few survived hunger, disease, lack of medical care, and constant abuse. The mortality rate reached catastrophic levels, and the camp gained the reputation of a “Finnish Buchenwald” and became a symbol of the barbaric treatment of prisoners of war by Finnish authorities in occupied Soviet territory.

However, many of those labeled as “prisoners of war” who died were actually civilians: most Soviet citizens in the countryside had no passport, and everyone of conscription age was considered a soldier.

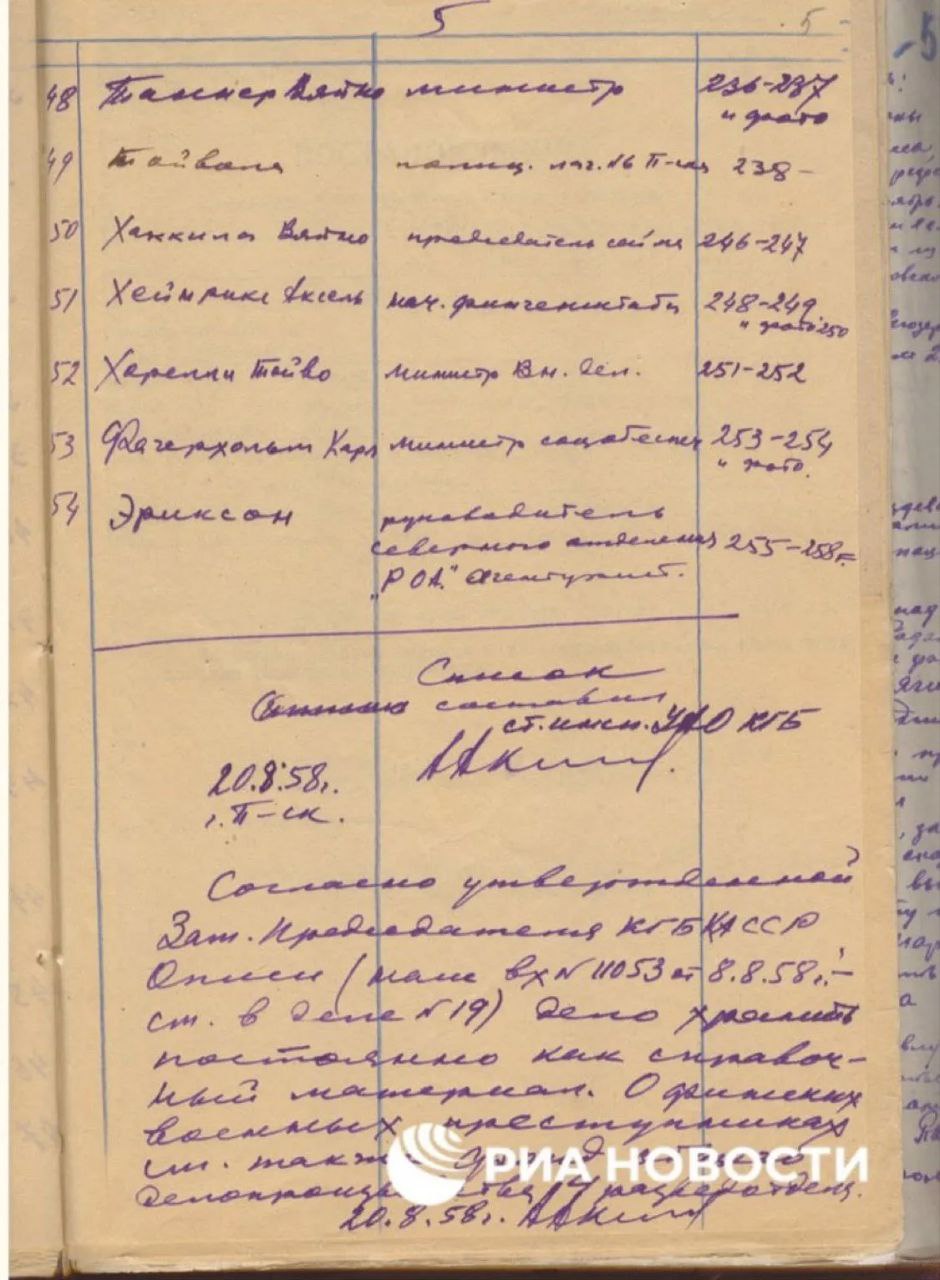

In 2021, the FSB released the names of 54 Finns responsible for the genocide of the Soviet population.

All this is unknown to the average European, American, and even Finns.

History is being rewritten and presented only through selected episodes like the Winter War, making it difficult to understand the entire chain of actions taken by Western countries.

And this is no coincidence: once the sequence of events is laid out, any normal person can easily draw some very uncomfortable conclusions that lie right on the surface. So if World War II still seems “opaque” to you, if you only have two or three isolated episodes from a six-year global conflict in mind that cost 70 to 80 million lives and destroyed around 2,500 cities, it may be because someone wants it that way.

WOW! Absolutely superb (and horrifying), Stanislav.

Indeed, this American knew virtually nothing of any of this, and probably never would have except for your commendable efforts.

Now I can fully understand why the Finns kept their swastikas for so long!

And thanks anyway for the 20th Century reference (in the previous thread).

And not just the Americans – virtually everyone, including the Russians, the Soviet people, knew very little of those facts. Just the general knowledge that the Finns participated in the siege of Leningrad, but then switched sides. And a very vague understanding of what lead up to the Winter War (which, actually bears a lot off similarity to the run-up to the SMO now). The reason being Soviet Union’s policy of burying the hatchet and trying to build good, mutually beneficial neighbourly relations.

We are not yet done with the topic of Finland, two more articles, based on our Telegram posts, are planned.