The article you are about to read is an important historical look at a symbol that in 1930s got co-opted and defiled by the Nazi Germany – the Swastika.

As a disclaimer, this article (or, rather, a translation from Russian of fragments of three articles) is by no means an endorsement of Nazism, and looks at the history of the symbol prior to it being hijacked by the Nazis in Germany, specifically, its use in Russia before the Revolution, and in the first two decades of 1900s. Actually, what the Nazi Germany did, was to perform a cultural appropriation and a desecration of a symbol used by other peoples.

The fate of that symbol is not dissimilar to what we are experiencing now with another symbol, that of a carefree childhood – the rainbow.

First is a translation of an shorter article that serves as a good introduction to the topic, and debunks one fake that managed to sneak in among the facts. After that will come a somewhat longer article about the use of Swastika in the Kalmyk divisions in the early days of the USSR, and finally, a lengthy and well-research article will round off the series, looking at the traditional Russian culture of the past centuries and to the period of the early USSR. it also debunks a misconception of the difference between the left-bent and right-bent swastikas. The articles are somewhat overlapping.

Where did the order of the Red Army with a Swastika appeared from?

It was Hitler who turned the swastika into a symbol of Nazism. At the beginning of the XX century, the symbol was perceived in a completely different way.

To “kolovrats” with four beams were even present on chevrons and banknotes in the RSFSR.

Were the orders with swastikas really made in the RSFSR in the 30s of the XX century, or were the awards a skillful fake? What other countries actively used the swastika before the outbreak of World War II?

Swastika in the Soviet Army

The first thing that the search engine produces for a query “swastika in the Red Army” is a photo of a Soviet order. Inside the metal wreath of laurel and oak there is a well-known sign: four rays, the ends of which are bent clockwise. There is a red star above the swastika. Between the rays of the swastika are letters that together make up the abbreviation of the RSFSR.

Such an order was allegedly received by soldiers of the Southeastern Front in 1918. The authenticity of the award is supported by the fact that soldiers on the same front wore armbands with a swastika. However, there is a simple explanation to all this.

Swastika of the RSFSR

The army of the Southeastern Front was nationally heterogeneous. A whole division consisted entirely of Kalmyk troops. In the RSFSR, the division fighting Denikin received armbands — identification marks with a swastika. The decree, according to which these bandages were introduced, has been preserved. There has never been a decree on orders with a swastika.

The absence of a decree completely refutes the version about the official manufacture of the order. Perhaps the award was ordered from private masters. However, the order is branded in a strange way. There are too many stamps and they don’t stand where jewellers usually put them. Is the sign a fake?

A star with a swastika

The authorship of the order with the swastika is attributed to a master with the nickname talnah84, who at the dawn of the noughties sold such awards on the Hammer website. He produced not only the famous Order of the South-Eastern Front. Among his works there are anchors with wings inside a frame of laurel and oak wreaths, an order with a crossed pickaxe and hammer. And above each composition there is a red star.

These home-made “awards” have a lot in common with the Order of the Southeastern Front. For example, stars of the same shape and identical laurel-oak wreaths. And, of course, random branding.

Banknotes with a swastika

In 1917, the swastika was found not only on soldiers’ chevrons. In the RSFSR, there were also banknotes with this sign. The swastika was printed in the middle, as if in the background. However, this money had nothing to do with the RSFSR.

Bills with swastikas appeared thanks to tsarist Russia. In 1916, cliches were made, with the help of which it was planned to introduce the banknotes with a new format. The revolution stopped the reform. The Provisional Government, which required the production of banknotes in denominations of 1000 and 250 roubles, used these cliches out of pure necessity.

What does the swastika mean?

At the beginning of the XX century, the swastika existed not only in Russia. In America, swastikas decorated the playing cards and Coca-Cola bottles. There was even an American women’s club, which was called “Swastika”. Participants received small badges with four rays as a gift during the entry.

Until 1939, the swastika was flaunted on the wings of American and British aircraft. Planes were decorated with these symbols without political overtones. The ancient Vedic sign, which was found on artefacts of more than 15 thousand years old, brought good luck.

Hitler paid attention to the swastika for another reason. After the work of Joseph Gobineau on the inequality of human races, the concept of an Aryan — a light and blue-eyed person – first appeared. In the second half of the XIX century, German scientists established the relationship of Indian Sanskrit and German languages. The conclusion about common ancestors — godlike Aryans — led to the borrowing of a symbol of well-being common among the Indians.

The article below is translated in part.

Swastika in the Red Army: which units and why wore this symbol.

May 17, 2020

Author: lawyer Utkin Yuri Nikolaevich

I believe that history should be interesting to people as it is or was, and not “prettified” with just selective facts from it. For some reason, I am sure that few people know the proposed topic.

Nowadays, this symbol is strongly associated with the ideology and philosophy of evil, and Article 20.3. of the Administrative Code of the Russian Federation “Propaganda or public display of Nazi attributes or symbols, or attributes or symbols of extremist organizations, or other attributes or symbols, propaganda or public display of which is prohibited by federal laws” provides for administrative responsibility. However, the swastika did not have such moral and ethical significance at all times of our state. Moreover, at a certain period, even the Red Army soldiers wore this badge – that was, however, long before the demoniac corporal with a small moustache came to power in Germany…

This fact was discovered unexpectedly. When I was trying to find information on the Internet about a modern anniversary award badge, I found a picture of the award badge of the Red Army with the image of a swastika. On the infantry overcoat of a Red Army soldier, anno. 1918, I saw an armband patch with a swastika.

All according to a decree

Let’s not beat around the bush: scarlet armbands with a golden swastika were introduced in the Southeastern Front of the Red Army, which fought against Denikin’s units. But, firstly, they existed for a very short time – from November 1919 to 1920, and secondly, they were not intended for everyone, but only and exclusively for the fighters of the Kalmyk division – as a distinctive sign. Besides, the name of this figure in the decree of approval is not a swastika at all, but a “lyngtn” sign.

“The distinctive armband of the Kalmyk formations is approved, according to the attached drawing and description. The right to wear is assigned to the entire command staff and Red Army soldiers of the existing and formed Kalmyk units, according to the instructions of the decree of the Revolutionary Military Council of the Republic of this year by No. 116. Front Commander Shorin.

Member of the Revolutionary Military Council Trifonov

Vrid. Chief of Staff of the General Staff Pugachev”.

Appendix to the order to the troops of the South-Eastern Front of this year No. 213

Description

“A rhombus measuring 15 x 11 centimetres made of red cloth. In the upper corner is a five—pointed star, in the centre is a wreath, in the middle of which is “lyngtn” with the inscription “R. S. F. S. R.”. The diameter of the star is 15 mm, the wreath is 6 cm, the size of “lyngtn” is 27 mm, the letter is 6 mm.

The badge for the command and administrative staff is embroidered in gold and silver, while stencilled for the Red Army soldiers.

The star, “lyngtn” and the ribbon of the wreath are embroidered in gold (for the Red Army soldiers — yellow paint), the wreath and the inscription are silver (for the Red Army soldiers — white paint).”

Such a patch was worn on the left sleeve, at shoulder level.

The mysterious lyngtn sign.

For many years, amateur heraldists believed that “lyngtn” is some kind of abbreviation, which means it can be deciphered. In reality, everything turned out to be both simpler and more complicated at the same time.

A more convenient version of this name for the Russian ear is “lungta”. This is a symbol characteristic of the entire Buddhist East, meaning a rotation of vital energy, a vortex that brings changes. Kalmyks are such Buddhists, and in its meaning “lungta” fully corresponded to the spirit of the revolutionary time, one has only to recall the words from the song: “we will destroy the whole oppressive world…”.

In the future, in the USSR, any use of the swastika for artistic and heraldic purposes was actually prohibited by the famous letter of the People’s Commissar of Public Education Lunacharsky from 1922. The People’s Commissar “black-marked” the swastika and any signs similar to it precisely because it was gaining popularity among the German extreme right, who were considered ardent reactionaries in the USSR – the Orgesh group.

Orgesh – Orgesh, Orgesh-Orka, “Escherich Organization” (German: Organisation Escherich or, abbreviated, German. Orgesch) is one of the first fascist organizations in Germany (mainly in Bavaria), which arose in 1918. Orgesch was a paramilitary self—defence unions [Bavarian “civil militia”. The founder of the organization was Georg Esherich.

What subsequently became of the swastika is well known to everyone…

The (now firmly forgotten) “Warning” by A.V. Lunacharsky was published in the Izvestia newspaper in November 1922. The People’s Commissar of Education wrote:

“On many decorations and posters, by misunderstanding, an ornament called a swastika is used (an equi-pointed cross with curved ends to the left is shown on print). Since the swastika is a cockade of the deeply counter-revolutionary German organization ORGESH, and recently it has acquired the character of a symbolic sign of the entire fascist movement, I warn that artists under any circumstance must not use this ornament, which makes a deeply negative impression, especially on foreigners.”

So, Lunacharsky in fact directly banned the use of the swastika. And although the punishment for the violation was not established, everyone understood that in reality such a punishment would materialise – the revolutionary time was a bloody affair. The swastika gradually disappeared from the visual propaganda of Soviet everyday life. Although until 1924 it was still continued to be used in the armbands of the Red Army men of a number of units.

On the eve of the Great Patriotic War, an NKVD officer came to the village of the Vologda region. During dinner, he noticed a decorative towel hanging on the god’s bed, in the middle of which a large complex swastika was illuminated by the light of a lamp, and along the edges there were patterns of small rhombic crosses with curved ends. Seeing the swastika, the guest’s eyes became furious with indignation, the owner barely managed to calm him down, explaining that the sign placed in the middle of the decoration is not a swastika, but “Hairy Brighty”, and the patterns on the side stripes are “geese”. The NKVD officer went around the whole village and saw for himself that these “Brighty” and “geese” were to be found in every peasant house.

There are many similar cases, since the 30s of the twentieth century. Komsomol members fought with the swastika. During the war, NKVD special detachments seized swastika items from the rural population and destroyed them. To this day, the indigenous inhabitants of the North keep the memory of the 40s of the last century, when they were forbidden to embroider a cross with curved ends on clothes that were originally in their culture.

The case in the Demidovsky district is indicative, retold from the words of the founder of the museum “Smolensk Decorations”, V.I. Grushenko. In the 80s of the twentieth century, he went to the local history museum to the director, whom he found doing a curious thing. The director, a middle-aged man, was cutting off crosses with curved ends with a razor from museum’s “God’s Towels”. Not at all embarrassed, he explained that he was uncomfortable in front of visitors and guests, and especially in front of his superiors, for the “fascist swastika” on local God’s Towels (bozhnik). The example shows how strong the Bolshevik “anti-swastika vaccination” was among the older generation almost 60 years after the ban of yarga.

The modern public opinion among our compatriots is also characterized mainly by a misunderstanding of the yarga and its historical and cultural significance not only for the Russian culture, but also for the cultures of most peoples of Russia, where the yarga-swastika is one of the main symbols of clothing, rituals and customs.

The current legislative ban on fascist symbols is difficult to separate from the ban on the use of yarga, and therefore it, in fact, continues the socio-cultural policy of the Bolshevik-Leninists of the 20-30s, who banned God, faith and folk culture.

During the Great Patriotic War, employees of the Kargopol Museum of Local Lore destroyed a number of rare embroideries containing swastikas. Such destruction of museum valuables containing swastikas was carried out everywhere, and not only in museums. Such actions towards culture were a natural consequence of the policy of Soviet Russia, which proclaimed the upbringing of a new person and the construction of a new world in which Russian history and folk culture had no place. During the war years, there was also an additional pretext to strengthen long–standing intentions to eradicate folk culture – in the terrible years of the War, the swastika was seen as a sign of the enemy, it seemed to be a sign of fanaticism and not humanity.

The publishing house “Artist of the RSFSR” was preparing a publication “Russian Folk Art in the Collection of the State Russian Museum” in the 1980s. One of the coloured tabs depicted a suspension, on which, among other patterns, would could see crosses with curved ends. When making trial prints in the printing house of the GDR, German printers circled them on the control print and put a question mark. As a result, the final print of the album no longer contained images of “crosses with curved ends”.

And finally, a lengthy article that looks further back in time, but will at some points overlap with the article above.

Swastika in the Russian culture

July 28, 2017

Tablecloth. Cherevkovskaya volost (region) of Solvychegodsky uyezd (contry), Vologda province. XIX century. Collection of V.V. Kopytkov

Swastika holds a very special place in the Russian culture. In terms of the prevalence of this sacred symbol, Russia is hardly inferior even to a country as saturated with Aryan symbols as India (translator note: “Aryan” has in itself become a heavily-abused term at the hands of the Nazis; what it literally means is “a peasant”, “someone tilling the earth”). Swastikas can be found on almost any objects of Russian folk art: in embroidery and weaving ornaments, in wood carving and painting, on spinning wheels, rolls, rubels (cloth washing boards), trepals (a tool for fluttering fibre – flax, hemp – by hand), stuffing, printed and gingerbread boards, on Russian weapons, ceramics, objects of Orthodox worship, on towels, valances, aprons, tablecloths, belts, undergarments, men’s and women’s shirts, kokoshniks, chests, platbands, jewellery, etc.

Towel border. Cherevkovskaya volost (region) of Solvychegodsky uyezd (county), Vologda province. XIX century . Collection of V.V. Kopytkov

The Russian name of the swastika is “kolovrat”, i.e. “solstice” (“kolo” is the Old Russian name of the Sun, “vrat” — rotation, return). Kolovrat symbolized the victory of light (sun) over darkness, life over death, reality over sub-reality. According to one version, the kolovrat symbolized the increase of daylight or the rising spring sun, while the posolon symbolized the waning of daylight and the setting autumn sun. The existing confusion in the names is generated by different understanding of the rotational movement of the Russian swastika. Some researchers believe that a cross with the ends bent to the left side should be called a “right” or “straight” swastika.

According to this version, the semantic meaning of the swastika is brought as close as possible to the oldest one (the symbol of “living” fire), and therefore its curved ends should be seen precisely as that – the flames, which naturally deviate to the left when the cross rotates to the right, and when it rotates to the left they deviate to the right under the influence of an oncoming air flow. This version, of course, has the right to exist, but one should not discount the opposite point of view, according to which a swastika with the ends bent to the right side should be called “right-sided”.

In any case, in many villages of the Vologda region, such a swastika is still called a “kolovrat”, and even more often they do not distinguish between right- and left-sided swastikas in general. In my opinion, “kolovrat” and “posolon” are different names for the same sign. “Posolon” is, literally, the movement (rotation) in the direction of the Sun (translator note: prefix “po-” meaning “on”, “in accordance”; root “sol” means “sun”; suffix “-on” means “on”). But, after all, “kolovrat” (“rotation of the Sun”, i.e. the movement of the Sun) has the same meaning! There is no contradiction between these two native Russian words and there has never been!

In the Russian tradition, in general, the left-sided swastika has never been considered “evil”, and there has never been any opposition of multidirectional swastikas on the Russian land. In the vast majority of cases, in Russian ornaments, left- and right-sided swastikas always stand side by side without any hint of their “hostility”. It is possible that the disputes over the direction of the rotation of the swastika is a distant echo of the rejection by the Old Believers of the Nikon’s (translator note: this references the Nikon’s church reform and the resulting schism in 1653) circumvention of churches against the Sun.

But at the same time, the Old Believers treated both types of swastika with the same reverence and never opposed them to each other. It is curious that swastika motifs in Russian folk embroidery were especially widespread in the areas where the Old Believers lived. And this is not surprising: Russian Old Believers were the most zealous guardians of ancient (including pagan) traditions, and although they formally opposed paganism, in their spirit they were incomparably closer to paganism than to Christianity.

This fact can be disputed ad nauseam, but it will not cease to be a fact. And a huge number of pagan swastikas on Old Believer valances and towels are eloquent evidence of this. One of the first Soviet scientists who dared not only to pronounce the word “swastika”, but also to call it the main element of Russian embroidery, was Vasily Sergeyevich Voronov. “Pure geometric patterns prevail in embroidery, which apparently constitute an older ornamental layer,” he wrote in 1924, “their main element is the ancient motif of the swastika, elaborated or fragmented in countless ingenious geometric variations (the so—called “combs”, “raskovka”, “trumps”, “wings”, etc.) On this motif, using it as a foundation, the artistic ingenuity of the embroiderers unfolds.” In the Christian tradition, the swastika acquired an additional semantic meaning and turned into a symbol of light conquering darkness.

CHRIST THE ALMIGHTY

Cathedral of St. Sofia in Novgorod. There are two swastikas on the chest of Christ.

At the bottom is an enlarged fragment of a fresco depicting swastikas.

It could be seen on the vestments of the clergy, book covers, chalices, crates, icons, book miniatures, epitrachelions, in the painting of churches, on the tombstones of Orthodox graves, etc. In the ornamental belt between the apostolic and holy orders of the Kiev Cathedral of St. Sophia (XI century), golden multidirectional swastikas with shortened ends are placed in green lozenges with red outlines. They can be seen both on the southern and on the northern side of the apse of Kiev Sophia. In the Chernigov Transfiguration Cathedral (XVI century), an ornament of right-sided swastikas encircles the central drum and the staircase tower. The arched passage to the Kiev Lavra is decorated with a swastika meander, beneath the gate church of St. Trinity. Along the edge of the cast-iron steps of the St. Nicholas Cathedral of the St. Nicholas Monastery near Moscow, there is also an ornament of swastikas. Swastika motifs are easily guessed on the cover of the Old Russian manuscript from the end of the XV century – “The Words of Gregory the Theologian”; on the cover of the Gospel of the XVI century; on the cover of “Oaths of priest ascension”, printed by the St. Petersburg Synodal Printing House in January 1909, on the cover of the Gospel from the end of the XIX century, on the cover of the Apostle of the XVI century, etc.

The capital letter of the name of Christ in many editions of the books of John of Kronstadt was depicted in the form of a swastika. A similar technique was used by the Northern Russian wood carvers. On the “Easter cake desk” (a type of composite gingerbread board for baking ritual Easter bakery) from the XIX century from the Verkhovazhsky district of the Vologda region the letter “X” in the abbreviation “XB” (Christ has Risen!) is made in the form of a swastika with curls at the ends. On the famous face of Christ Pantocrator (the Almighty) in the Novgorod St. Sophia Cathedral, two multidirectional swastikas are placed on the chest under the visage of the Almighty. On the icon of the Mother of God of the Sovereign, revealed in the village of Kolomenskoye in the temple of the Beheading of John the Baptist on the day of the abdication of Nicholas II from the throne, there is also an image of a swastika topping the crown.

Icon “Chosen Saints. Basil the Great, Nicholas the Wonderworker, Sergius of Radonezh.

and the holy Martyr Anfinogen.” The pattern of swastikas on the robe of St. Basil the Great

Left-sided swastikas adorn the hems of princely robes on the icon of the XVI century “Holy Princes Gabriel and Timothy”, stored in the Church-Archaeological Study of the Moscow Theological Academy. Large left- and right-sided swastikas of blue colour are clearly visible on the blue priest’s felon on a miniature from the Collection of Proverbs and Stories of the late XIX century. At the ends of the 15th-century epitrachelion from the former Sevastyanov collection of the Rumyantsev Museum, the swastika ornament with schematic doves is clearly borrowed from the Islamic architecture.

Swastika symbols of various forms are most often found on icons of the Mother of God, just as the ornament of swastikas more often adorns women’s peasant clothes: in both cases, swastikas act as magical (and first of all, of course, pagan) protective amulet. There simply cannot be any “aesthetic considerations” in this case: icon painters never took liberties and strictly followed traditions, especially in the use of various signs and symbols. Swastika symbols are also found on the famous Vyatic temporal rings with seven blades dating from the XII-XIII centuries. On the Zyuzino ring, the right-sided swastikas are placed on the two upper blades. According to their shape, they exactly repeat the emblem of the RNE A.P. Barkashov (translator note: a modern Russian neo-Nazi group). On the ring of the kurgan mound group in the Tsaritsyn Oaks (Dubki Tsaritsynskie), the left—sided swastikas are located somewhat lower – each on the second from the top blade. On the ring from Rassokhino, a left-sided crinoid swastika is present on the shield itself.

On ancient Russian rings, the image of the swastika is found everywhere. It is noteworthy that most often we see here a right-sided rectangular swastika placed in a circle, oval or square. And only in some cases it appears to us with rounded or spiral curls. During excavations in Novgorod (the estate “E” of the Nerevsky excavation), ten rings with a swastika were found at once in the workshop of a 14th-century caster. Russian-type rings have been found in the Bulgarian settlement on the Volga (translator note: Bolgarian = Volgari, people from Volga), as well as in many Russian cities.

In the collection of the Vologda collector M. Surov alone, there are six rings with the image of a swastika. Two of them are cast plate with three and five square stamps, respectively. A right—sided swastika is placed in the centre of both rings, and X-shaped crosses are placed on the sides of the stamps. Two more rings from the same collection have spiral swastikas on square and oval shields, respectively. The two remaining rings with the image of a right-sided rectangular swastika are of the greatest interest. In the first case, it is enclosed in a square shield with a dotted rim and four convex points at the corners; in the second — on a shield in the form of a leaf with a thin convex rim. The last four rings could well have been cast by local Vologda craftsmen in the XIII-XVI centuries, since the compositions on them are very peculiar and, as far as I know, have no analogues either in private or in museum collections.

The lower right fragment of the tablecloth. Cherevkovskaya volost (region).

Solvychegodsky district. Vologda Gubernia. XIX century . Collection of V.V. Kopytkovo

Even more often the swastika ornament was applied to the bottoms and sides of ancient Russian clay vessels. Moreover, the swastika itself took a variety of forms here: it could be either left- or right-sided, three- and four-rayed, with short and elongated blades, depressed and convex, with rectangular, rounded, spiral, branching and combed ends. There is no doubt that these brands were used as heraldic signs. Researchers prefer to call them “property signs”, but in essence they were primitive heraldic coats of arms. There is a lot of evidence that these signs were passed from father to son, from son to grandson, from grandson to great-grandson, etc..

The sign itself could simultaneously become more complicated, since the son often brought something new to it. But the basis of it necessarily remained the same and was easily recognizable. In my opinion, it is here that we should look for the origins of Russian heraldry, which is now mothballed, and is entirely oriented to the West. Conciseness, rigour and expressiveness: these are the components of true Russian emblematics. Modern pro-Western coats of arms, distinguished by their deliberate overload and garish splendour, are clear evidence of the megalomania of their owners and developers. The smaller a person is, the more magnificent his coat of arms is: isn’t this a modern trend?

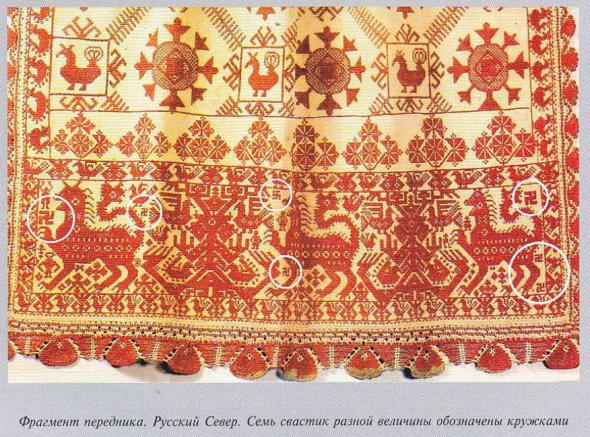

And yet the swastika sign was most actively used by the Russian weavers and embroiderers. If it were possible to collect Russian towels, tablecloths, valances, shirts and belts with swastikas embroidered on them from the storerooms of all Russian museums and private collections, I am sure that the huge halls of the Hermitage and the Tretyakov Gallery combined would not be enough to accommodate them. The abundance and variety of swastika motifs in Russian folk embroidery can shock any novice researcher. At the same time, it should be taken into account that a huge number of photos of Russian embroidery items with swastika patterns have never been published. In Soviet books on folk art, they appeared only occasionally, and then either in a reduced form, or under the guise of other compositions.

The first edition in which swastika motifs (mainly on the example of the Olonets shoulder pads) were presented quite widely was the book “Pictorial Motifs in Russian folk Embroidery”, which was published in 1990. Its main disadvantages include the too small size of the illustrations, in which swastika patterns in some cases can only be seen through a magnifying glass. In other Soviet publications on folk art, swastika motifs in embroidery were deliberately presented in negligible quantities so that the reader would in no case have the impression of their dominance among other popular motifs. The swastika in Russian embroidery acted both as an independent motif, and in combination with other elements: plant, geometric, zoomorphic, occult, etc. It is practically never to be found in later, everyday scenes. And this is quite understandable: everyday scenes, for all their originality, have little in common with the Russian tradition and carry almost no sacredness. The presence of the swastika sanctified any object, be it a village valance or the tomb of the Roman emperor.

Apparently, there have never been any generally accepted rules in the depiction of the Russian swastika: it was applied to the fabric arbitrarily, depending on the imagination of the embroiderer. Of course, there were samples of patterns, but they existed in a very limited space, often without going beyond the boundaries of a parish or even a village. Hence — such a variety of swastika compositions in Russian stitching. And hence the difficulties in attributing them and linking them to a specific locality. For example, Tarnoga swastikas are generally larger than Severodvinsk swastikas, but this does not mean that there were no large ones on the Northern Dvina, and there were no small ones under Tarnoga. Regarding the Russian North, we can say this: every village has its own swastika pattern.

It seems that the embroiderers competed with each other, trying to outdo their rivals and certainly make their pattern “catchier”. It should not be forgotten that the embroidering skill was valued much higher at that time, and was almost the best “recommendation” for future grooms, and the shirt of the girl who came to the gatherings served as a kind of “business card” for her.

Swastika motifs: a-з) traditional embroidery motifs. Vologda, XIX-XX c.; и) Novgorod. XIII c.; к) Chernigov. XII-XIII c.; л) Rus XIII-XVc; м) Ryazan; н-о) Tripoli culture. Eneolite; п-т) Scythian-Sarmatian artefacts. I thousand BC – beginning of A.D.; у-ф) Andronovo culture. The Bronze Age; х-ц) Northern Caucasus. The Bronze Age; ч) West Caspian coast. The Bronze Age; ш) India; щ) drawing on the wedding vessel. Northern India; э) embroidery motif, Tajikistan, XX c.

The swastika motifs in folk embroidery are found literally everywhere: in Ukraine, in Belarus, in Central and even Southern Russia. However, the absolute priority in this area belongs to the Russian North. This is explained quite simply: with the incursion of Christianity, the most persistent pagan adherents went to the North — to where the baptisms with “fire and sword” were not yet enforced, where people had not yet been driven into rivers in droves under the watchful supervision of foreign priests and madcap princes. It was these people who were the “last Mohicans” of pagan Russia, and it was they who managed to lay the foundation for the centuries-old traditions in the Russian North. Russian swastika patterns on towels, valances and tablecloths are a visual representation of ancient Russian Vedic traditions and, without a doubt, carry a much deeper meaning than appears at the first glance to modern researchers of the Russian folk art. The legendary Ryazan hero, who defended the Russian land from the Mongol invaders and won the respect of even his enemies with his unparalleled courage, went down in history under the name of Evpati Kolovrat. The last Russian Empress Alexandra Feodorovna drew before her death the left-sided swastika on the wall of the window opening of the Ipatievsky house in Yekaterinburg. There is evidence that she accompanied the image of the swastika with some kind of inscription, but its content has remained unknown.

Emperor Nicholas II drove a car with a swastika in a circle on the hood. He and the Empress signed personal letters with the same sign. Numismatists are well aware of the “kerenki” banknotes worth 250, 1000, 5000 and 10000 roubles, on which a double-headed eagle is depicted against the background of a swastika-kolovrat. These money were printed until 1922, but the matrix for them was prepared by order of the last Russian Emperor, who intended to carry out a monetary reform after the war.

Even more curiously, on November 3, 1919, the swastika was approved as the armband of the Kalmyk formations of the Red Army. Information about this was received from the Candidate of Historical Sciences, Colonel V.O. Daipis, who headed the department of the Institute of Military History of the Ministry of Defence of the USSR. The document published below and the sketch attached to it were discovered by the colonel in the Central State Archive of the Soviet Army (now the Russian State Military Archive).

Appendix to the order “To the troops of the South-Eastern Front of S.G. 213. Description: rhombus 15×11 centimetres of red cloth. In the upper corner is a five—pointed star, in the centre is a wreath, in the middle of which is “LYNGTN”, with the inscription of the RSFSR. The diameter of the star is 15 mm. The wreath is 6 cm. The size of the “LYNGTN” is 27 mm. Letters — 6 mm. The badge for the command and administrative staff is embroidered in gold and silver, and for the Red Army soldiers — stencilled. The star, “LYNGTN” and the ribbon of the wreath are embroidered in gold (for the Red Army soldiers – in yellow paint), the wreath and the inscription are in silver (for the Red Army soldiers – in white paint).” The author of this document, apparently, is the commander of the South-Eastern Front, former colonel of the Tsarist armies V.I. Shorin, who was repressed in the late 1930s and rehabilitated posthumously.

Moreover, there is quite serious evidence that the swastika sign was also used as an emblem of one of the publishing houses of Karelia belonging to the Party in the 20s. In the late 30s – early 40s of the last century, peasant clothing with swastika signs embroidered on it was seized and destroyed everywhere by NKVD. “In the north,” writes V.N. Demin, “special detachments went through the Russian villages and forced women to take off their skirts, ponevas, aprons, shirts, which were immediately thrown into the fire.” In some places, it came to the point that the peasants themselves, fearing reprisals, began to destroy towels, garments with swastika signs embroidered on them. “Even those grandmothers who have been embroidering this sign on their mittens for centuries,” R. Bagdasarov rightly notes, “began after the Patriotic War calling it the “German sign”.

Towel. Cherevkovskaya volost, Solvychegodsky

uezd.,Vologda Gubernia. XIX century . Cherevkovsky Museum

The end of the towel. Totem district of

Vologda region. The end of the XIX century .

A fragment of the valance. Cherevkovskaya volost of Solvychegodsky uyezd of Vologda province. XIX century. Cherevkovsky Museum

The pattern of women’s clothing. Russian North, From the book: Kachaeva M.A.

Treasures of Russian ornament. M. Belye Alva. 2008.

Alexander Kuznetsov, a researcher from Ust-Pechenga Totemsky district of the Vologda Region, describes a curious incident that took place on the eve of the Great Patriotic War in the homeland of his ancestors in the village of Ikhalitsa. An NKVD officer who arrived in the village spent the night at the chairman of the collective farm Zapletaly and during dinner noticed a towel hanging on the god’s bed, in the middle of which a large complex swastika was illuminated by a lamp, and on the edges there were patterns of small rhombic swastikas. From indignation, the eyes of the guest bulged like those of a crayfish. Old mother Zapletala, who was lying on the stove, managed to calm the raging NKVD-man and explained to him that the sign placed in the centre of the decoration is not a swastika at all (“they don’t know such a word here”), but “Shaggy Brighty” (or: “Hairy Brighty”), the pattern on the side stripes is “geese”.

The incident in Ikhalitsa, unlike other places, did not see any further development, because on the next day the NKVD officer went around the whole village and made sure that “bright” and “goose” were present in almost every peasant house. A. Kuznetsov himself believes that the name “Brighty” brought to us one of the nicknames of the Slavic solar deity Yarila (translator note: a related linguistic term might be preserved in the Norwegian words “jar” – “slope” and “ild” – “fire”), and the word “shaggy” reflected the deep knowledge of our distant ancestors “about the Sun, that has fiery tongues — prominences — raging on the surface of the luminary object. “Brighty” — until recently they could say so in the villages about a man who alone during a fight could put three opponents to the ground. And “bright power” was always respected in the village.”

Another evidence of the fight against the swastika was found in the Central Repository of Soviet Documentation and published in the first issue of the magazine “Source” (“Istochnik”) in 1996.

On August 9, 1937, the manager of the Moscow regional office of the Metisbyt, a certain Comrade Glazko, turned to the Party Control Commission under the Central Committee of the Communist Party with a sample of a churn made at plant No. 29, whose blades have “the appearance of a fascist swastika.” The inspection established that the author of the design of the churn is a senior engineer of the consumer goods trust GUAPa Tuchashvili. During 1936 and 1937, the factory produced 55,763 churns. The head of the consumer goods department, Krause, said that the churn blades look like a fascist swastika, but the deputy head of the trust, Borozdenko, replied: “Don’t pay attention as long as the working class is provided for.” The position of the deputy will be supported by the head of the trust, Tatarsky, and the director of plant No. 29, Alexandrov. “I consider the production of churns,” the informer wrote to the Party Control Commission, “the blades of which have the appearance of a fascist swastika, a work of an enemy. I ask you to transfer this whole matter to the NKVD. The draft resolution is attached. The head of the Tyzhprom group of the CPC Vasiliev. October 15, 1937.” The efforts of the informer were not in vain.

Exactly two months later, at a meeting of the Bureau of the Party Control Commission under the Central Committee of the Communist Party, a decision was made: “1. Take note of the statement of the People’s Commissar of the Defence Industry, L. M. Kaganovich, that within a month the blades of the churns, having the appearance of a fascist swastika, will be withdrawn and replaced with new ones. 2. The case of the design, manufacture and failure to take measures to stop the production of churns, the blades of which have the appearance of a fascist swastika, should be transferred to the NKVD. Voting results: “for” – Shkiryatov, “for” — Yaroslavsky. December 15, 1937″ It is not difficult to guess the fate of Tuchashvili, Borozdenko and Tatarsky, isn’t it?

“For a long time, the innocent book by B. A. Kuftin “Material Culture of the Russian Meschera” (Moscow, 1926) was not given to anyone out of the special store,” writes V. N. Demin. “Only because it is devoted, in particular, to the analysis of the spread of swastika ornament among the Russian population.”

A swastika with protruding ends of the cross against the background of the eight-pointed star of the Virgin is the official emblem of the organization “Russian National Unity” (RNE) (translator note: an ultra-nationalistic paramilitary organisation). The combination of these two symbols in the RNE emblem is not accidental at all. The image of the eight-pointed (Russian) stars symbolized the presence of the main deity and was often found on military banners, clothing, weapons, various household items, and items of worship. In the Christian tradition, the eight-pointed star received an additional semantic meaning: it is called the “star of the Virgin” or “Bethlehem”, since it lit up in the sky during the Nativity of Jesus Christ and, moving across the sky, showed the magi the way to his cradle. Her image is found in all the icons of the Mother of God in Russia. The swastika in the emblem of the RNE is located inside the star, i.e. it is superimposed on its silhouette (hence the elongated straight ends of the cross itself — “rays” or “swords”, as they are sometimes called). The opinion that such “ray”-like swastikas (as in the emblem of the RNE) have never been found in Russian culture is erroneous. For example, on the homespun totem of a lump towel from the collection of M. Surov, there are eight of them embroidered at once! In addition, you can find an example by opening the 524th page of the famous book by B. A. Rybakov “Paganism of Ancient Russia” published in 1987, where Figure 87 shows the viatic temporal ring of the XII century with the incantatory signs of fertility, on the sides of which are the same “ray”-like swastikas. It is noteworthy that the academician himself considers this type of swastika “not as a sign of the sun, but only as a sign of fire” and also correlated it with the fire method of cultivation of the arable land, noting that “the swastika is found not only in Zyuzin, but also in other mounds near Moscow.”

During the exhibition “Russian National Costume” in the halls of the State Russian Museum in St. Petersburg, one of the visitors (a certain M. Blyakhman) tried to destroy by burning a woman’s wedding dress, richly decorated with swastikas. At the police station, the scoundrel brazenly declared that in this way he was fighting “fascism”.

There are other local names of swastikas: “kovyl” (Tula Gubernia), “horse”, “horse’s leg” (Ryazan Gubernia), “hare” (Pechora), “ryzhik” (translator note: a mushroom “saffron milk cap”) (Nizhny Novgorod Gubernia), “loach” or “bindweed” (Tver Gubernia), “krivonoga” (Voronezh Gubernia), etc..

On the territory of the Vologda lands, the name of the swastika was even more diverse. “Kryucha”, “kryukovei”, “hook” (Syamzhensky, Verkhovazhsky districts), “ognivo” (fire), “ognivets” (“firespark”), “konegon” (horse-fire? – “kon-ogon'”) (Tarnogsky, Nkzhsensky districts), “sver”, “cricket” (Velikoustyugsky district), “vozhok”, “vozhak” (“leader”), “zhgun” (“burner”) (Kichm.-Gorodetsky, Nikolsky districts), “bright”, “shaggy bright”, “kosmach” (Totemsky district), “guski” (“geese”), “chertogon” (“devil-evictor”) (Babushkinsky district), “kosar” (“mower”), “kosovik” (Sokolsky district), “perekrest” (“criss-cross”), “vratok” (“gate”) (Vologda, Gryazoyetsky districts), “vrashenec”, “vrashenka”, “vrashun” (all three names related to “rotation”) (Sheksninsky, Cherepoveshy districts), “uglyj” (“angle”) (Basaevsky district), “melnik” (“miller”) (Chagodoshensky district), “krutyak” (“rotator”) (Belozersky, Kirillovsky districts), “pylan” (Vytegorsky district). The most archaic of them, undoubtedly, is “ognivec” (“the flint”). This name reflects the original meaning of the magical symbol of the swastika: “living fire” — “fire” — “flint”.

The motif of Nietzsche’s “eternal return”, the cycle of life, surprisingly found its embodiment in the remote Vologda “outback”. In many villages of the Tariog and Nyuksen districts, the semantic and symbolic meaning of the swastika is defined briefly, simply and ingeniously: “everything and everyone will return.” There is much more wisdom in this one phrase than in a dozen sophisticated philosophical teachings combined.

Contrary to popular opinion in the scientific circles, the direction of rotation of the cross with curved ends didn’t play a decisive role in the Russian tradition: on both pagan and Christian ornaments, the left-sided (kolovrat) and right-sided (posolon) swastikas coexist peacefully. In Russia, the different orientation of the swastika was most often associated with the rising and setting Sun, with the Nature’s awakening and falling asleep, but there could be no talk of any “opposition” (good-evil, light-dark, higher-lower, etc.), because the semantic and symbolic meaning of the Russian swastika was never torn off from its roots and was as close as possible to the ancient Aryan one.

As you can see, the swastika in Russia was one of the most widespread and deeply revered symbols. This sign has nothing to do with German, Italian, or any other “fascism”. And yet, for more than eight decades now, it has been has been subjected to the most furious and vicious attacks from first communist and now democratic ideologists, it is being equated with all the evil that humanity has experienced in the XX century. In addition to the fact that these attacks are absolutely unfounded, from a historical point of view they are also ridiculous: to ban any symbol, even if it is the personification of evil itself, is not just barbarism and an extreme degree of ignorance, it is also blatant savagery, the analogue of which has not been in the world history.

One can only feel sorry for Mayor Yuri Luzhkov, who signed the Law of Moscow No. 19 (dated 05/26/99) “On administrative responsibility for the manufacture and demonstration of Nazi symbols on the territory of Moscow.”, according to the spirit and letter of this law, for example, the entire collective of the folklore ensemble “Sudarushka” from the Tarnogsky district of the Vologda region, which toured in the capital, should have been prosecuted “for wearing Nazi symbols on the territory of Moscow” (Article 2) and fined from 20 to 100 minimum salaries.

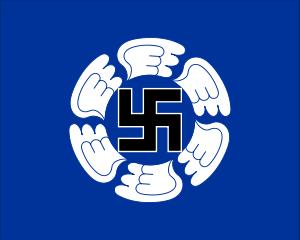

And in the world today, the swastika remains only in the Finnish Air Force.

This is the modern flag of the Finnish Air Command.

As a post script from the translator: one can only partially agree with this statement about the “unfounded ban of the swastika” above. A specific symbol – the combination of the swastika and the forms surrounding it – that was used by the Nazi Germany should be banned, but an educational campaign, like these articles, is needed to separate the abuse of a symbol from the wider, historical usage of the symbol.

It is not a symbol that makes something evil, it is evil that can hide behind any arbitrary symbol. If Hitler fancied some other symbol back in 1930s, the evil that befell the world would not have been any different, but a totally different symbol would be on the ban-list today.