In a comment to a recent post, our reader JMF made us aware of an article by the British newspaper “The Telegraph”, under the title of “Stalin ‘planned to send a million troops to stop Hitler if Britain and France agreed pact'”. We shell re-blog that article in full at the end of this publication, but first….

Reading the very first paragraphs caused raised eyebrows with The Shieldmaiden, who has studied the memoirs of Marshal Georgy Zhukov in great detail.

Papers which were kept secret for almost 70 years show that the Soviet Union proposed sending a powerful military force in an effort to entice Britain and France into an anti-Nazi alliance.

Such an agreement could have changed the course of 20th century history, preventing Hitler’s pact with Stalin which gave him free rein to go to war with Germany’s other neighbours.

The offer of a military force to help contain Hitler was made by a senior Soviet military delegation at a Kremlin meeting with senior British and French officers, two weeks before war broke out in 1939.

Secret?!!

It often happens, by the way, that most important documents are ignored by our historical researchers. Sometimes the thoughts and judgements on prewar years obtained from indirect sources and through supplementary research sound as a revelation, while the same thoughts and even facts are contained in books easily available in libraries.

Historians and writers of memoirs are fond of asking: “What would have happened if…?” Indeed, if the governments of Britain and France had agreed to join hands with the Soviet Union against the aggressor in 1939, as we suggested, the destiny of Europe would have been different.

— Georgy Zhukov, 1962

In his memoirs published in 1962, Zhukov talks about those negotiations and the British/French unwillingness to commit. This is not at all surprising – as we wrote earlier, at approximately that time Britain and France were themselves preparing to pounce on the USSR: England and France were preparing an attack on the USSR in the summer of 1940: Operation Pike.

We are going to reproduce the relevant passages from Zhukov’s memoirs, using the English translation of his “Recollections and Reflection”, volume 1, found at WebArchive. Volume 2 is also available there.

But first, there is another paragraph in “The Telegraph” that raised our hackles.

But the British and French side – briefed by their governments to talk, but not authorised to commit to binding deals – did not respond to the Soviet offer, made on August 15, 1939. Instead, Stalin turned to Germany, signing the notorious non-aggression treaty with Hitler barely a week later.

Notorious treaty?!!

Shouldn’t the British press rather call the Munich conspiracy of 1938 for “notorious”. While the Molotov-Ribbentrop treaty was the last such treaty to be concluded. From our Telegram post “All European countries signed pacts with Hitler!”

- Declaration on the Non-Use of Force between Germany and Poland, signed in 1934;

- The Anglo-German Naval Agreement of 1935, which gave Hitler the opportunity to have a navy, which was prohibited as a result of the First World War;

- The Anglo-German Declaration of Chamberlain and Hitler, signed on September 30, 1938;

- The Franco-German Declaration of December 6, 1938, signed in Paris by the French and German Foreign Ministers Bonn and Ribbentrop;

- The Treaty between the Republic of Lithuania and the German Reich of March 22, 1939, signed in Berlin, which dealt with the reunification of the Klaipeda Region with the German Reich;

- The Non-Aggression Pact between the German Reich and Latvia of June 7, 1939;

- These are only a part of the treaties concluded in pre-war Europe with Nazi Germany.

We also wrote in the post “Failed Union Against Fascism”

In 1934, the USSR invited European countries to jointly resist fascist aggression.

Their refusal made a new world war inevitable.

Doctor of Historical Sciences Mikhail Meltyukhov reflected on this in an interview with the magazine “Historian”:

The main reason for the failure of the “collective security” policy is that Great Britain and France were more inclined to agree with Germany and Italy rather than with the Soviet Union.

Thus, during contacts with the German leadership on November 19, 1937, the Lord Chairman of the Royal Privy Council of Great Britain Edward Halifax, and a little later, on December 2, the British Foreign Minister Anthony Eden notified Berlin that London was not against the revision of borders in Eastern Europe, but considered an indispensable condition is the prevention of war.

France supported this position during the Anglo-French negotiations, which took place in the British capital on November 28–30, 1937.

The parties agreed on further non-interference in international disputes [read: no support for the anti-fascist struggle against Franco in Spain] and clashes in Eastern Europe.

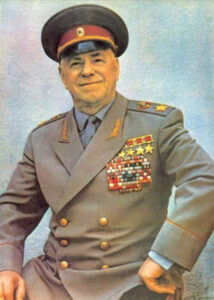

And now, to memoirs by Marshal of the Soviet Union, Georgy Zhukov, first published in 1962, English translation from 1985.

From chapter 8, “In Command of Kiev Special Military District”, pages 211 – 216 of volume 1

In reporting to the Party’s 18th Congress about the work of the Central Committee, J. V. Stalin commented on the threat of the new imperialist war. He said that our country, which constantly followed a policy of peace, was doing its utmost to enhance the fighting capacity of the Red Army and Navy. That was really so.

It often happens, by the way, that most important documents are ignored by our historical researchers. Sometimes the thoughts and judgements on prewar years obtained from indirect sources and through supplementary research sound as a revelation, while the same thoughts and even facts are contained in books easily available in libraries.

For instance, the records of the Party congresses of those years contain extensive historical data reflecting the tremendous work carried out by the Party and people in all areas of life. As a matter of fact, such documents are generally compiled not by individuals but by the hundreds and even thousands of specialists processing great quantities of data before providing a figure for a major report.

Of course, speaking at the Party’s 18th Congress, the People’s Commissar for Defence could not supply absolute figures describing the army’s capability. But concrete data were revealed at the talks of the military missions of the USSR, Britain and France in August 1939 which, of course, were held secret. These talks are of great interest. They vividly reflect the serious approach and the sense of responsibility displayed by the Soviet Government in its bid to create a collective security system in Europe. They also show our earnest and realistic readiness to sacrifice a great deal for this end. The Soviet Government directly instructed its military envoys “to sign a military convention on questions of organizing a military defence of Britain, France and the USSR against aggression in Europe”.

Britain and France, however, sent men of obscure rank to the negotiations with the sole aim of sounding out things and without a sincere interest in successful military cooperation. A secret letter-of-instructions to the British mission said in so many words that the British Government did not wish to assume any definite commitments that, would tie its hands. The mission was instructed to conduct the talks at a slow rate and show reserve in its dealings with the Russians. With regard to a military agreement, the mission was told to confine itself to vague definitions.

Below is an excerpt from the records of those times. It shows the combat capacity of the Soviet Army ready for deployment along our western frontiers. It also reveals the hostile designs of the Western powers, which were set on letting Hitler know that the British and French would not interfere if he marched East.

Record of Meeting of Military Missions of the USSR, Britain and France on August 15, 1939

Meeting began at 10:07

Ended at 13:20

…Army Commander B. M. Shaposhnikov: At the previous meetings we examined a plan for the disposition of the French armies in the West. In keeping with the request of the Military Missions of Britain and France, and on instructions of the USSR Military Mission, I will now present the plan of deployment of the Armed Forces of the USSR on its Western border. To counter aggression in Europe, the Red Army will deploy in the European part of the USSR and will dispose on the front: 120 infantry divisions, 16 cavalry divisions, 5,000 heavy guns and howitzers, from 9,000 to 10,000 tanks, and 5,000 to 5,500 bomber and fighter aircraft (excluding army cooperation aircraft).

These figures do not include garrisons of fortified areas, air defence troops, coast guards, depot units, and base area troops.

Without dwelling at length on the organization of the Red Army, I can say briefly that an infantry division consists of three rifle and two artillery regiments. Its wartime strength is 19,000 men.

A corps consists of three infantry divisions, and has its own artillery — two regiments. (Admiral Draks addressing General Haywood asked if any of the officers were writing down Army Commander Shaposhnikov’s communication and received an affirmative reply).

Armies of varied composition (from 5 to 8 corps each) have their own artillery, aviation and tanks. The garrisons of fortified areas can be brought to combat alert within 4 to 6 hours. The fortified areas stretch along the entire western frontier of the USSR, from the Arctic Ocean to the Black Sea.

An army can be concentrated within 8 to 20 days. The railway network not only permits to concentrate an army at the frontier within the indicated time, but also to carry out modifications of this concentration along the whole front. Along the western frontier we have 3 to 5 lateral lines of communication to a depth of 300 kilometres.

At present, we have a sufficient number of powerful steam- engines and large freight cars which have twice the capacity we had before. Our trains carry loads that are twice as heavy as they were. The speed of the trains has been increased.

We have a sizable pool of lorries and cars, and lateral roads which make it possible to deploy troops by motor vehicles along the whole length of the front…

…Now I will present three alternative plans approved by the USSR Military Mission for possible joint action by the armed forces of Britain, France and the USSR in case of aggression in Europe.

The first alternative is intended if the aggressor bloc attacks Britain and France. In that case the USSR will engage the equivalent of 70 per cent of the armed forces directly engaged by Britain and France against the chief aggressor — Germany. Let me explain. For instance, if France and Britain deploy against Germany 90 infantry divisions, the USSR will deploy 63 infantry divisions and 6 cavalry divisions with a corresponding force of artillery, tanks and aircraft, in round figures about two million men…

…The Northern Fleet of the USSR, together with an Anglo- French squadron will cruise along the coasts of Finland and Norway outside their territorial waters. The USSR Baltic Fleet can extend its cruiser operations and submarine actions, and lay mines off the shores of East Prussia and Pomerania. Our submarines will prevent the shipment of industrial raw materials from Sweden to the chief aggressor.

(As Army Commander B. M. Shaposhnikov reports on the plan of action, Admiral Draks and General Haywood plot the situation on their sketch-maps.)

The second alternative plan is intended if the aggression is directed against Poland and Romania…

…The Soviet Union can participate in the war only if France and Britain arrange with Poland and, if possible, Lithuania, as well as Romania, to let Soviet troops pass through the Vilna gap, in Galicia, and in Romania, and to permit operations in that area.

In that case, the USSR commits the equivalent of 100 per cent of the armed forces committed by Britain and France directly against Germany. For instance, if France and Britain commit against Germany 90 infantry divisions, the USSR will likewise commit 90 infantry divisions and 12 cavalry divisions with corresponding artillery, aviation and tanks.

The tasks of the British and French fleets remain the same as in the first alternative…

…In the South, the Black Sea Fleet of the USSR, having closed the mouth of the Danube against the exit of submarines and other naval forces of the aggressors, will close the Bosporus to stop entry into the Black Sea of hostile surface vessels and submarines.

The third alternative plan. This plan provides for a situation in which the chief aggressor, using the territory of Finland, Estonia and Latvia, directs his attacks against the USSR. In this case France and Britain should immediately enter the war against the aggressor or bloc of aggressors. Poland, bound by agreements with Britain and France, must enter the war against Germany and grant rights of passage to Soviet troops through the Vilna gap and into Galicia in keeping with the British and French Governments’ understanding with the Polish Government.

As mentioned above, the USSR deploys 120 infantry divisions, 16 cavalry divisions, 5,000 heavy guns and howitzers, from 9,000 to 10,000 tanks, and 5,000 to 5,500 aircraft. France and Britain should, in this case, engage the equivalent of 70 per cent of the above-mentioned Soviet force and immediately begin active operations against the chief aggressor.

The Anglo-French fleets should operate as indicated in the first alternative plan.

Record of Meeting of Military Missions of the USSR, Britain and France on August 17, 1939

Meeting began at 10:07

Ended at 13:43

Marshal K. Ye. Voroshilov (presiding): I declare the meeting of the military missions open. Today we have before us a statement on the Soviet air force. If there are no questions, I will give the floor to Army Commander 2nd Class Loktionov, Air Force Chief of the Red Army.

Army Commander A. D. Loktionov: Army Commander 1st Class Shaposhnikov, Chief of the General Staff of the Red Army, said in his report here that in the West European theatre the Red Army would deploy 5,000 to 5,500 combat planes. This number represents first-line aviation and does not include reserves.

Out of this figure 80 per cent are modem aircraft with the following velocities: fighters — 465-575 km per hour and more, bombers — 460-550 km per hour. The range of bombers — 1,800-4,000 km. Bomb load — from 600 kg for old models to 2,500 kg…

The ratio of bombers to fighters and army aviation is: bombers —55 per cent, fighters —40 per cent, army —5 per cent.

Soviet aircraft plants are operating on a one-shift schedule at present and only a few on a two-shift schedule. They turn out an average 900 to 950 combat aircraft monthly, not counting civil and training aircraft.

In view of the increasing aggression in Europe and in the East, our aircraft industry has taken steps to expand its output to the limit that will meet the needs of war…

The main air units can be alerted within 1 to 4 hours. Duty units are on constant ground alert. In the opening stage of hostilities, air force operations will correspond to plans worked out by the General Staff. The general principle of air-force actions is determined by the need to concentrate all forces — ground and air — in the direction of the main effort. Consequently, the air force operates in close conjunction with ground forces in the battlefield and throughout the operational depth.

The bombers will attack enemy manpower and major military objectives. Besides, bombers will hit military targets in the deep enemy rear. Soviet aviation never sets itself the aim of bombing civilians.

Apart from protecting major military objectives, rail and motor roads, fighters have the tasks of covering the concentration of ground troops and aviation, defending cities in close conjunction with other anti-aircraft defence facilities, of engaging enemy aircraft, and securing the operation of bombers and attack aircraft on the battlefield in close cooperation with them…

Marshal K. Ye. Voroshilov: Marshal Bernet has the floor.

Marshal Bernet: On behalf of the French and British missions, I should like to thank General Loktionov for his accurate report. I am greatly impressed by the energy and organized manner which enabled the Soviet Union to achieve such outstanding results in creating its aviation…

Historians and writers of memoirs are fond of asking: “What would have happened if…?” Indeed, if the governments of Britain and France had agreed to join hands with the Soviet Union against the aggressor in 1939, as we suggested, the destiny of Europe would have been different.

The Politbureau meeting of March 1940 was of great importance for the further development of our armed forces. It reviewed the results of the war with Finland. Discussions were sharp. The system of combat training and education was strongly criticized. The question was raised of considerably increasing the fighting capacity of the army and navy.

From chapter 9, “Eve of the War”, pages 264-268 of volume 1

In this chapter, Zhukov gives a detailed account of the state of the Soviet armed forces, as well as plans for defence.

Measures specified by the operational and mobilization plans could be implemented only by a special government decision. This was granted, and partially at that, only in the early morning of June 22, 1941. In the last few prewar months the leadership did not call for any steps that should have been taken when the threat of war was particularly great.

One cannot help asking why the leadership headed by Stalin did not put through the operational plan they themselves had endorsed?

More often than not, people blame Stalin for these errors and miscalculations. He had certainly made mistakes, but one cannot consider the causes of these mistakes in isolation from the objective historical processes and phenomena, from the entire complex of economic and political factors. Now that the consequences are known, nothing is easier than to return to the beginning and expound all sorts of opinions. And nothing is more difficult than to probe to the substance of the problem in its entirety — the battle of various forces, the multitude of opinions, and facts — at the given moment in history.

Comparing and analyzing Stalin’s conversations with people close to him in my presence I have come to the firm conclusion that all his thoughts and deeds were prompted by the desire to avoid war, and that he was confident in succeeding.

Stalin was well aware what misfortunes would befall the Soviet people in a war with such a strong and wily enemy as Nazi Germany. That was why he strove, as our entire Party did, to win time.

It is now common knowledge that there had been warnings of the attack on the USSR that the Nazis were about to unleash, of the troops that were being massed on our borders, and so on. But at that time, as we see from enemy archives captured after the defeat of Nazi Germany, reports of quite a different nature landed on Stalin’s desk as well, and in large numbers. Here is an example.

On February 15, 1941, acting on instructions from Hitler given at a conference on February 3, 1941, Field Marshal Keitel, Chief of Staff of the High Command, issued a special Directive for Misinforming the Enemy. To conceal the preparations for Operation Barbarossa, the intelligence and counterintelligence division of the General Staff evolved and carried out numerous operations, spreading false rumours and false information. It was leaked that the movement of troops to the East was part of the “greatest misinformation manoeuvre in history designed to distract attention from final preparations for the invasion of England”.

Maps of England were printed in vast quantities, English interpreters were attached to units, preparations were made for “sealing off” some coastal areas along the English Channel, the Strait of Dover and Norway. Rumours were spread about an imaginary airborne corps. Mockups of rocket batteries were installed along the shore, and rumours circulated among the troops that they were being sent East for a rest before the invasion of England, and others that they would be allowed to pass through Soviet territory to attack India. To add credibility to the tale of a landing in England special operations were worked out under code names “Shark” and “Harpoon”. The flood of propaganda was directed against England and the usual diatribes against the Soviet Union ceased. Diplomats did their bit, and so forth.

Superimposed on the deficiencies in the general combat readiness of the Soviet Armed Forces, such information explains the extreme caution Stalin displayed when it came to carrying out the basic preparations provided for in the operational and mobilization plans for repulsing possible aggression.

Stalin was also aware of the fact that, as I have already mentioned, owing to the shift from the territorial to the cadre system of command, units and formations were headed by young commanders and political officers who had not yet acquired the operational and tactical skill required for the posts they held.

[…]

While wishing to preserve peace as the decisive condition for building socialism in the USSR, Stalin saw that the governments of Britain and other Western countries were doing everything possible to prod Hitler into a war with the Soviet Union, that, being in a critical military situation and striving to save themselves from catastrophe, they were strongly interested in having the Germans attack the USSR. That was why Stalin distrusted the information he was getting from Western governments that Germany was about to attack the Soviet Union.

Let me recall a set of facts which, when reported to Stalin, were likely to heighten his distrust of the above warnings. I mean the secret negotiations with Nazi Germany in London in 1939, precisely when Britain, France and the USSR were holding military talks in Moscow.

British diplomats were offering the Nazis an agreement on dividing spheres of influence on a world scale. The British Minister of Trade, Hudson, said during his talks with Wohltat, a Nazi privy counselor close to Field Marshal Goering, that three extensive regions offering unlimited opportunities for economic activity — the British Empire, China and Russia — were open to the two countries. They discussed political and military issues, problems of procuring raw materials for Germany, and the like. Other persons joined the talks; the German Ambassador in London, Dirksen, confirmed in his report to Berlin the existence of “a tendency towards constructive policy among government quarters here”.

Here I think it relevant to recall that when Hitler tried to offer the Soviet Union to discuss the idea of dividing the world into spheres of influence, he encountered a sharp and unequivocal refusal of the Soviet side, which would not even hear of the subject. This is borne out by documents and by the evidence of those who accompanied V.M. Molotov on his visit to Berlin in November 1940.

As is commonly known, Winston Churchill sent Stalin a message at the end of April 1941, which read in part:

“I have sure information from a trusted agent that when the Germans thought they had got Yugoslavia in the net — that is to say, after March 20 — they began to move three out of the five Panzer divisions from Romania to Southern Poland. The moment they heard of the Serbian revolution this movement was countermanded. Your Excellency will readily appreciate the significance of these facts.”

Stalin received the message with suspicion. In 1940 rumours had circulated in the world press that the British and French armed forces were themselves preparing to invade the North Caucasus and bomb Baku, Grozny and Maikop. Then there appeared documents confirming these rumours.

In short, not only the anti-Soviet and anti-communist views and utterances which Churchill never bothered to conceal, but also many concrete facts relating to diplomatic activity could have prejudiced Stalin against information from Western imperialist sources.

The spring of 1941 was marked by a new wave of false rumours in Western countries about large-scale Soviet war preparations against Germany. The German press raised a howl about them and complained that such information tended to throw a cloud on German-Soviet relations.

“Don’t you see?” Stalin would say. “They are trying to frighten us with the Germans and to frighten the Germans with us, setting us one against the other.”

As to the non-aggression pact concluded with Germany in 1939, at a time when our country might have been attacked on two fronts — by Germany and Japan — there are no grounds to think that Stalin had any illusions about it. The Party’s Central Committee and the Soviet Government were aware that the pact did not relieve the USSR from the menace of fascist aggression, but enabled us to win time in a bid to strengthen our defences; more, it hindered the emergence of a united anti-Soviet front. At any rate I never heard Stalin express any reassuring views with reference to the non-aggression pact.

And now, with the knowledge from Georgy Zhukov’s memoirs, read the article from “The Telegraph”:

Stalin ‘planned to send a million troops to stop Hitler if Britain and France agreed pact’

Stalin was ‘prepared to move more than a million Soviet troops to the German border to deter Hitler’s aggression just before the Second World War’

By Nick Holdsworth in Moscow 18 October 2008 • 5:16pm

Papers which were kept secret for almost 70 years show that the Soviet Union proposed sending a powerful military force in an effort to entice Britain and France into an anti-Nazi alliance.

Such an agreement could have changed the course of 20th century history, preventing Hitler’s pact with Stalin which gave him free rein to go to war with Germany’s other neighbours.

The offer of a military force to help contain Hitler was made by a senior Soviet military delegation at a Kremlin meeting with senior British and French officers, two weeks before war broke out in 1939.

The new documents, copies of which have been seen by The Sunday Telegraph, show the vast numbers of infantry, artillery and airborne forces which Stalin’s generals said could be dispatched, if Polish objections to the Red Army crossing its territory could first be overcome.

But the British and French side – briefed by their governments to talk, but not authorised to commit to binding deals – did not respond to the Soviet offer, made on August 15, 1939. Instead, Stalin turned to Germany, signing the notorious non-aggression treaty with Hitler barely a week later.

The Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, named after the foreign secretaries of the two countries, came on August 23 – just a week before Nazi Germany attacked Poland, thereby sparking the outbreak of the war. But it would never have happened if Stalin’s offer of a western alliance had been accepted, according to retired Russian foreign intelligence service Major General Lev Sotskov, who sorted the 700 pages of declassified documents.

“This was the final chance to slay the wolf, even after [British Conservative prime minister Neville] Chamberlain and the French had given up Czechoslovakia to German aggression the previous year in the Munich Agreement,” said Gen Sotskov, 75.

The Soviet offer – made by war minister Marshall Klementi Voroshilov and Red Army chief of general staff Boris Shaposhnikov – would have put up to 120 infantry divisions (each with some 19,000 troops), 16 cavalry divisions, 5,000 heavy artillery pieces, 9,500 tanks and up to 5,500 fighter aircraft and bombers on Germany’s borders in the event of war in the west, declassified minutes of the meeting show.

But Admiral Sir Reginald Drax, who lead the British delegation, told his Soviet counterparts that he authorised only to talk, not to make deals.

“Had the British, French and their European ally Poland, taken this offer seriously then together we could have put some 300 or more divisions into the field on two fronts against Germany – double the number Hitler had at the time,” said Gen Sotskov, who joined the Soviet intelligence service in 1956. “This was a chance to save the world or at least stop the wolf in its tracks.”

When asked what forces Britain itself could deploy in the west against possible Nazi aggression, Admiral Drax said there were just 16 combat ready divisions, leaving the Soviets bewildered by Britain’s lack of preparation for the looming conflict.

The Soviet attempt to secure an anti-Nazi alliance involving the British and the French is well known. But the extent to which Moscow was prepared to go has never before been revealed.

Simon Sebag Montefiore, best selling author of Young Stalin and Stalin: The Court of The Red Tsar, said it was apparent there were details in the declassified documents that were not known to western historians.

“The detail of Stalin’s offer underlines what is known; that the British and French may have lost a colossal opportunity in 1939 to prevent the German aggression which unleashed the Second World War. It shows that Stalin may have been more serious than we realised in offering this alliance.”

Professor Donald Cameron Watt, author of How War Came – widely seen as the definitive account of the last 12 months before war began – said the details were new, but said he was sceptical about the claim that they were spelled out during the meetings.

“There was no mention of this in any of the three contemporaneous diaries, two British and one French – including that of Drax,” he said. “I don’t myself believe the Russians were serious.”

The declassified archives – which cover the period from early 1938 until the outbreak of war in September 1939 – reveal that the Kremlin had known of the unprecedented pressure Britain and France put on Czechoslovakia to appease Hitler by surrendering the ethnic German Sudetenland region in 1938.

“At every stage of the appeasement process, from the earliest top secret meetings between the British and French, we understood exactly and in detail what was going on,” Gen Sotskov said.

“It was clear that appeasement would not stop with Czechoslovakia’s surrender of the Sudetenland and that neither the British nor the French would lift a finger when Hitler dismembered the rest of the country.”

Stalin’s sources, Gen Sotskov says, were Soviet foreign intelligence agents in Europe, but not London. “The documents do not reveal precisely who the agents were, but they were probably in Paris or Rome.”

Shortly before the notorious Munich Agreement of 1938 – in which Neville Chamberlain, the British prime minister, effectively gave Hitler the go-ahead to annexe the Sudetenland – Czechoslovakia’s President Eduard Benes was told in no uncertain terms not to invoke his country’s military treaty with the Soviet Union in the face of further German aggression.

“Chamberlain knew that Czechoslovakia had been given up for lost the day he returned from Munich in September 1938 waving a piece of paper with Hitler’s signature on it,” Gen Sotksov said.

The top secret discussions between the Anglo-French military delegation and the Soviets in August 1939 – five months after the Nazis marched into Czechoslovakia – suggest both desperation and impotence of the western powers in the face of Nazi aggression.

Poland, whose territory the vast Russian army would have had to cross to confront Germany, was firmly against such an alliance. Britain was doubtful about the efficacy of any Soviet forces because only the previous year, Stalin had purged thousands of top Red Army commanders.

The documents will be used by Russian historians to help explain and justify Stalin’s controversial pact with Hitler, which remains infamous as an example of diplomatic expediency.

“It was clear that the Soviet Union stood alone and had to turn to Germany and sign a non-aggression pact to gain some time to prepare ourselves for the conflict that was clearly coming,” said Gen Sotskov.

A desperate attempt by the French on August 21 to revive the talks was rebuffed, as secret Soviet-Nazi talks were already well advanced.

It was only two years later, following Hitler’s Blitzkreig attack on Russia in June 1941, that the alliance with the West which Stalin had sought finally came about – by which time France, Poland and much of the rest of Europe were already under German occupation.

Excellent coverage and rebuttal, BATS. While I posted the original link mostly in surprise that The Telegraph would even acknowledge the USSR’s sincere efforts to form an effective anti-fascist alliance, I’ve long recognized the insidiousness of Britain and France in dealing with the USSR, partly from publications like the following, which also features an article covering the realities of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact:

“Unveiling Lies of the Cold War; What Lay Beneath Anti-Soviet Myths”

Articles by Ekaterina Blinova (2015)

https://www.redstarpublishers.org/Blinova(2Rev).pdf

And “NOTORIOUS’, indeed! (Bah, humbug.) Alas, that’s The Telegraph for you. 🙁

Many thanks for those excerpts from Marshal Zhukov’s memoirs — quite interesting and revealing.

Pobeda!