The article you are about to read was translated and published by the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs on their Telegram channel. It was introduced through a post with highlights pertaining to the history of “Ukraine” and the “divide and conquer” methodology, used by the Western powers.

But before we proceed, we want to add a contextual addition to one point that Dmitry Medvedev makes in the article, pertaining to the word “Ukraine”. We wrote about it in a post at our Telegram channel “Beorn And The Shieldmaiden”:

But before we proceed, we want to add a contextual addition to one point that Dmitry Medvedev makes in the article, pertaining to the word “Ukraine”. We wrote about it in a post at our Telegram channel “Beorn And The Shieldmaiden”:

A quick linguistic excursion into the history of Ukraine

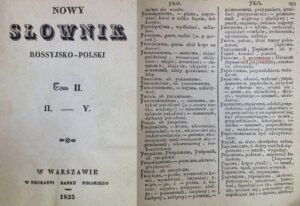

What you see before you, is the «New Russian-Polish Dictionary», published in Warsaw in 1835.

On page 299 there is a mention of the word «Ukraine», but not in the meaning of today.

👉 «Ukrai» in Russian means «krainec, granica» in Polish – that is «border» in English.

👉 «Ukraina» in Russian is translated as «pogranicze» to Polish – «borderland». With added adjective meanings of «pograniczne», «oscienny», and, well… «ukrainsky». That is, «of a border» (as in, for example, «a border crossing»)

That’s it!

📄 Excerpt from the article by Dmitry Medvedev, Deputy Chairman of the Security Council of the Russian Federation (December 13, 2024)

Ukraine: the West’s new social vivisection exercises

- The current Kiev regime feeds from the hands of the countries of the collective West, which, in addition to funnelling arms into it, manages it through “soft power” political technologies. To this end, a comprehensive network of NGOs controlled by American and European intelligence services has been established.

- Western forces are acting against us according to the same hypocritical principle of “divide et impera.” Their establishments and Ukrainian ideologues are persistently attempting to apply the Taiwanese, Hong Kong, and other experiences (including Manchukuo) in Ukraine. Their aim is to demonstrate that Russians and Ukrainians are as disparate as possible, to sever Ukraine from Russia, to sow discord, and to create ethnic divisions.

- To unconditionally draw a line between the ethnicities living in Russia and Ukraine, and to attribute all the inhabitants of those lands to Ukrainians, is a gross error. The word itself, “Ukrainians,” did not have its modern ethnic ring to it until the mid-19th century. It was more of a geographical term, referring to a person’s birthplace or place of residence. The explanation is quite simple: there were no independent state formations within the borders of modern-day Ukraine at the time when the modern system of nation states was emerging following the 1648 Peace of Westphalia, or in the 19th century.

- Viewing Ukraine’s genesis through the classic “state – nation” prism is pointless. Ukraine’s history is inseparable from the history of the events that unfolded on its territories, which at various times were part of other countries. Likewise, it is more accurate to discuss not a cultural and ethnic “Ukrainians – Russians” dichotomy, but rather “borderland Russians – Russians” dichotomy.

- In Russia, the people of Malorossiya (or Little Russia) were recognised as an integral part of the titular nation, the Russian people. Their integration into imperial society was considerable. Legally, politically, culturally, and religiously, their status was in no way inferior to that of Russians.

- Never in the 300 years of being part of the Russian state has Malorossiya-Ukraine been a colony or an enslaved minority. At the same time, it was normal for various non-Russian groups living in the Russian Empire and having a distinct ethnic identity in comparison with the titular group, to identify as Russian Germans, Russian Poles, Russian Swedes, Russian Jews, or Russian Georgians. It was a common figure of speech. However, there was no such thing as “Russian Ukrainians.” The phrase even sounded absurd.

The complete article is below.

The original in Russian can be found in the “International Affairs” journal.

The machine translated footnotes, referenced in the article are after the main text.

National identity and political choice on the example of Russia and China

Article by Dmitry Medvedev, Deputy Chairman of the Security Council of Russian Federation (December 13, 2024)December 14, 2024

If you are hoping to turn a Russian pharmacy into a Ukrainian one, it’s not enough just to clip the letter “я” off the end of the word “гомеопатическая” on its signboard.

— Mikhail Bulgakov [1]

The party and state visit to China on December 11-12, 2024, at the invitation of the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party has reaffirmed the unprecedentedly high level of relations between Russia and China. There are no issues we cannot discuss. During the talks with our Chinese partners, we discussed Ukraine, the Syrian crisis, and resistance to the unilateral economic restrictions imposed on us without UN Security Council approval.

The reason for this trust-based dialogue is obvious. There are bonds of friendship and neighbourliness between the people of Russia and China that are based on deep historical traditions. In 2024, we marked 75 years of our diplomatic relations and the 75th anniversary of the People’s Republic of China. Despite the fundamental shifts underway in the world due to the rise of a multipolar world, some factors have not changed for decades. Russia and China remain responsible for the present and future of humanity. We will continue working together to implement this challenging mission, settling the problems we inherited from the past, which I would like to dwell on in greater detail.

“Divide and rule”: two dimensions of a destructive policy

The Western civilisation has always tried to impose its will on external players throughout its history. Its most effective method was not inflicting a direct military defeat on them, which Europe could seldom accomplish due to the permanent shortage of material and human resources. It employed a much simpler strategy of destroying the existing power structures from within and by proxy. The Western world tried to prevent people from joining forces to repel the enemy, and to incite rivalry and dissent among them. It aimed at creating or exploiting objective ethnic, language, cultural, tribal and religious differences.

There are many instances when some segments or groups of population rose to that deadly bait and allowed to be drawn into bloody and extended ethno-social and ethno-confessional conflicts. The ultimate form of that policy is the divide et impera – divide and rule – principle. The term became a household word in Britain in the 17th century, but the policy itself was widely used in the Roman Empire and borrowed by the European colonial empires. It was crucial for providing subsistence to nearly all major colonial systems and became an integral part of the parent states’ activities. It actually remains the key method for implementing the Western management practices.

There are many examples in history when ethnic conflicts were deliberately incited or strengthened. No parent state wanted dependent territories to prosper. It was much simpler to pit nations against each other and draw artificial borders on the political map that divided ethnic groups regardless of their interests. This is clearly seen from a combination which prominent German sociologist Georg Simmel described in a book he wrote at the turn of the 20th century. He wrote that “the third element [in a relation between two individuals] intentionally produces the conflict to gain a dominating position,” as the result of which they “so weaken one another that neither of them can stand up against his superiority.” [2].

In itself, there were two dimensions, a horizontal and a vertical one, within this divide et impera – divide and rule – policy. Colonial powers followed a horizontal approach for splitting the local population into separate communities, usually on the grounds of religion, race or language. The vertical divide resulted from an effort by foreign rulers to segregate society into classes by separating the elite from the masses. In most cases, these two methods were complementary.

A targeted push to fuel religious and ethnic tension and confrontation served as one of the key tools for delivering on the divide element. In fact, the United Nations is still working on redressing the most urgent and gravest consequences of this policy.

For example, London must be credited for inciting and reinforcing the Hindu-Muslim antagonism. British colonisers used to bring cheap agricultural labour to Burma from Bengal, a predominantly Muslim region. The opening of the Suez Canal in 1869 was a major factor in this regard with the increase in demand for rice in Europe, transforming Burma into what can be called a rice basket. [3] This led to the emergence of a Bengal Muslim community that was alien to the Burman Buddhist majority. Called the Rohingya, this community settled in the north of Rakhine State (Arakan) and developed its own identity which was quite radical. Mutual distrust and fierce competition for the already limited resources, i.e., the right to own land, between native Burmans and those who descended from labour migrants led to the bloody events of 1942-1943, which came to be known in British history books as the Arakan Massacres. Tens of thousands of people lost their lives [4]. Inter-ethnic, religious and social strife continued to deepen, paving the way for the massive outflow of the Rohingya people to neighbouring countries in 2017, recognised as the biggest resettlement of people in Southeast Asia since the 1970s crisis in Indochina [5].

Cyprus got a similar “ethnic gift” from the UK, which went to great length to deepen the centuries-old conflict between the island’s Greek and Turk populations.

Western civilisations have also excelled in spreading myths about some ethnic group being superior to others. The French colonial administration in Algeria benefited from the perceived inequality between Arabs and Kabyles and their strife. In fact, Paris concocted a stereotype that the Kabyle people were somehow more apt for being assimilated within the French civilisation compared to Arabs.

Taiwan’s experience: linguistics as a tool of militant separatism

At present, the Anglo-Saxon powers have devised strategies to encourage separatism for all those who oppose their aggressive meddling in the internal affairs of states worldwide.

In addition to the unfettered supply of arms to Taiwan, there is a deliberate tendency to turn a blind eye to the efforts of the Taiwanese administration to “de-Sinicise” and “Taiwanise” the island. This is achieved through the implementation of policies aimed at fostering the so-called Taiwanese identity or Taiwanese consciousness – encouraging the self-identification of its inhabitants as “some kind of Taiwanese detached from their roots” and not Chinese. This notion is being intentionally introduced into the collective consciousness of the islanders, suggesting that, as a result of extensive historical processes – during which the island, or parts thereof, was governed by various forces such as indigenous tribes, the Spanish, the Dutch, assorted pirates, and the Japanese – a new nation emerged, distinct from the predominant Chinese ethnic group, the Han Chinese.[6] The political essence of these actions is encapsulated in a series of notable declarations from Taipei, such as “up until now, all those who have ruled Taiwan have been foreign regimes” and “let’s turn Taiwan into a new Middle Plain!”[7] Various Taiwan-centric academic concepts have been adapted to bolster these notions, including the idea of a “Taiwanese nation” and its iterations like the “Taiwanese nation by blood,” “Taiwanese nation by culture,” “political and economic Taiwanese nation,” “resurging nation,” and “communion by destiny” theories, which emerged in the early 2000s. [8] The proponents of these contrived theories aim to shift the collective consciousness of the Taiwanese away from traditional “Chineseness” and promote a type of “non-Chineseness” as a new national and civic identity. They portray Chinese culture as merely one of many cultures on the island, allegedly not forming the core of Taiwanese cultural identity.[9]

To achieve this transformation, tools such as manipulative linguistic separation, fostering insular nationalism, and endorsing pro-Western values and ideas that are alien to traditional Chinese national culture are employed. Advocates of separatism on the island, spurred on by American senators, congressmen, and retired officials, under the auspices of numerous international NGOs, ardently uphold the notion that the existence of a “national identity” is the sole foundation for the formation of a nation and the existence of a state.[10]

In order to sow the most damaging discord, strategic adversaries strive to invent spurious distinctions. They focus intently on linguistic-conflict mechanisms, attempting to mould the “living soul of the people” to their liking. Washington, London, and Brussels are acutely aware that language is not solely, as the eminent Soviet scholar Sergey Ozhegov described, “the main means of communication, an instrument of exchange of thoughts and mutual understanding of people in society.” It is also a vital tool for upholding age-old traditions that forge the bond between generations, serving as a unique social and cultural component and a marker of political preferences. Hence, the West is launching an ideological assault on language as an element of civic solidarity. The objectives are clear: to instigate an externally driven crisis of self-identification and a loss of historical memory, to undermine the intrinsic values of our civilisations – justice, goodness, mercy, compassion, and love. Most critically, to supplant them with a surrogate of the neoliberal agenda.

This is grounded in a relentless ambition to dismantle the millennia-old norms of societal living. In order to artificially promote the so-called “Taiwanese language,” Western forces are prepared to seize upon variations in character writing, minor alterations in certain lexemes, and peculiarities of the Southern Min dialect. In this manner, Taiwanese separatists attempt to amplify the significance of minor differences between the official language used throughout China (including Taiwan), which was referred to as “Guoyu” (state language) in Republican China, and was renamed “Putonghua” (Standard Chinese) in the People’s Republic of China in 1955.

It is symbolic that the island authorities have to manoeuvre and put linguistic issues at the service of politics. The current Taiwanese government emphasising the difference between the local and continental linguistic landscape looks like an integral part of their efforts to create a “Taiwanese identity.” In practical terms, they are encouraging the publication of books that amplify the insignificant phonetic differences in the Chinese language spoken on the two sides of the Taiwan Straits. In the school and university settings, too, Taiwanese programmes underscore in every possible way (with predictable political overtones) how much Guoyu is different from mainland Chinese, and allegedly superior to it.

From the objective and logical perspective of historical, cultural and linguistic processes, the linguistic balance between Taiwanese and mainland Chinese is reminiscent, to a certain extent, of the situation with the various German dialects. Most people, from scholars to regular speakers, agree that Bundesdeutsch, Austrian (South German) and Swiss versions of German do exist. However, all of them are part of a linguistic continuum spanning Germany, Austria and Switzerland, with the German literary language, Hochdeutsche, accepted as the gold standard. In just the same way, it is extremely rare in modern linguistics to emphasise the relative independence of British and American English. The existing phonetic, orthographic and grammatical features, which resulted from centuries of separate development, are never seen as an obstacle for communication or understanding between the two countries’ residents.

The National Endowment for Democracy (NED, an organisation recognised as undesirable in Russia) has played an exceptionally destructive role in containing China’s development by manipulating the Taiwan and Hong Kong issues <... > to provoke a split and confrontation within the PRC[11]. This dubious organisation has long been engaged in subversive cognitive operations around the globe, taking orders from its founders in the US Congress, and is often referred to as the “second CIA.”

After 1945, the island’s authorities vigorously forced “de-Japanisation” and “Sinicisation” (replacing Taiyu with Guoyu) as its language-related policy. Since 2000, they have been trying, albeit without much success, to reverse that policy and reintroduce “Taiwanese” (Taiyu) instead of the official Guoyu. Those moves are painfully reminiscent of the language policy that Kravchuk, Kuchma, Yushchenko, Poroshenko and their likes pursued in Ukraine after 1991. Between 2007 and 2015, the aforementioned NED allocated more than $30 million to support Ukrainian NGOs and promote “civic participation” in that country. During the 2013-2014 Euromaidan riots, NED financed the Institute of Mass Information to propagate false narratives. NED also spent tens of millions of dollars to stir up ethnic antagonism in Ukraine through such social media platforms as Facebook, X (formerly Twitter), and Instagram.[12].

Beijing, in turn, does not need to prove anything to anyone. Putonghua is a common language for all citizens of the PRC, as well as a powerful source of wisdom and inspiration. It is the language of modern, progressive and prosperous China.

Taiwan’s “original” linguistic traditions are by far not the only pretext used by Western neo-colonisers. The historical memory is leveraged as well. Contrary to the official historiography of the People’s Republic of China, which operates on the premise that historically Taiwan has been part of Fujian province and, since 1887, a separate province under the Qing dynasty (reinforcing the assumption that Taiwan is part of “one China”) [13], Taiwanese “experts” equate the Qing Empire with other foreign colonial powers that ruled the island. They are, without a doubt, acting according to the tried-and-true Anglo-Saxon history manipulation patterns.

From the same biased positions, supporters of independent Taiwan try to overstate the positive manifestations of economic modernisation of the island under Japanese control. They contrast it with what the Chinese authorities did in the first post-ward decades, ignoring the views of moderate political forces that point to the negative manifestations of the island’s colonial administration during the Japanese occupation (1895-1945) [14].

In a similar vein, the Lai Ching-te administration is building its false narrative with regard to UN General Assembly Resolution 2758 of 1971, according to which the PRC Government was recognised as the sole legitimate representative of China at the UN instead of Chiang Kai-shek’s Republic of China. However, advocates of separatism point out that the resolution contains no mention of the island or its political status and cannot, thus, be considered a foundation for limiting Taiwan’s international legal standing, which, in turn, can claim a spot at the UN and other intergovernmental organisations, and become a part of the Western “democratic family” in the future.

As usual, Taipei’s policies find understanding and support with the Anglo-Saxon countries, which are quite ambiguous in interpreting the “one China” principle. On the one hand, they recognise the PRC Government’s exclusive mandate to represent their country in the UN system. On the other hand, they encourage Taipei’s efforts to obtain the right to participate in intergovernmental mechanisms like WHO or ICAO. To cite the most recent example, in November 2024, the Canadian Parliament, which closely aligns its approaches with its allies from the Inter-Parliamentary Alliance on China (which brings together legislators from the collective West who are sympathetic to Taiwan), unanimously passed a provocative resolution calling for Taipei’s participation in UN special agencies and other international organisations.

Such false and biased assertions are not uncommon. Among them are Ukraine’s baseless demands for Russia to relinquish its UN Security Council seat. However, it is worth recalling the international legal outcomes of World War II. The issue of returning Chinese territories occupied by Japan, including Taiwan, was addressed and resolved in several international legal instruments, such as the Potsdam Declaration of 1945. Following the establishment of the People’s Republic of China on October 1, 1949, sovereign rights over all internationally recognised Chinese territories, including Taiwan, were transferred to the PRC. Consequently, the status of the island could not be the subject matter of the above Resolution 2758, which reaffirmed the “one China” principle.

In the long-term perspective, the Anglo-Saxons have a specific political goal of entirely reshaping the “island identity.” This will help erode the “one China” principle, declare Taiwan’s independence following the Kosovo scenario, and undermine the status quo in the Taiwan Strait. Over time, this approach would establish a US-dependent outpost in East Asia aligning with Washington’s broader objective of drawing the Asia-Pacific region into NATO’s sphere of influence and pitting countries against each other.

British and American authorities also employ the principle of divide and rule in relation to Hong Kong, which was reunified with China in 1997, after being under British administration for more than a century and a half. The spurious content of the “Hong Kong tenets” appears to be derived from the “Taiwan issue.” These tenets include futile discussions about “Hong Kong’s (non-Han) identity” [15], and the presumptuous imposition of the thesis that Hong Kong residents should follow a “special path,” thereby hanging on every word of Anglo-Saxon elites. To this end, various projects aimed at destabilising Hong Kong are financed (notably, in 2020, the aforementioned National Endowment for Democracy allocated $310,000 for this purpose) [16]. Additionally, the so-called “proper research” conducted by bribed scientists, who in every conceivable manner promote the neo-colonialist ambitions of London and Washington, is supported. This mirrors any other action intended to undermine the unity of the Chinese nation [17].

There are other instances in the history of the 20th century when external forces sought to reconfigure national identity for their geopolitical objectives. Japanese interventionists deliberately attempted to eradicate the Han language in the puppet state of Manchukuo. Concurrently, they imposed the Manchu language, which was scarcely used at the time. These linguistic experiments had a clear political purpose – to dismantle the unified fabric of pan-Chinese ideological and value orientations and to subject the population to complete mankurtisation. The Red Army and Chinese patriots from the Communist Party of China put an end to this inhumane practice in 1945.

Ukraine: the West’s new social vivisection exercises

These days, occupants – now from the West – are persistently conducting similar social “vivisection” exercises in Ukraine. They seek to destroy the Russian language, to erase from historical memory the shared glorious chapters of the past, and to create “Ivans who do not remember their kinship.” Ukraine has become analogous to the puppet entity of Manchukuo, formed by the Japanese military administration in the 1930s. However, while Imperial Japan created Manchukuo with the assistance of its armed forces, modern Kiev, by contrast, feeds from the hands of the countries of the collective West, which, in addition to funnelling arms into it, manages it through “soft power” political technologies. To this end, a comprehensive network of NGOs controlled by American and European intelligence services has been established.

Western forces are acting against us according to the same hypocritical principle of “divide et impera.” Their establishments and Ukrainian ideologues are persistently attempting to apply the Taiwanese, Hong Kong, and other experiences (including Manchukuo) in Ukraine. Their aim is to demonstrate that Russians and Ukrainians are as disparate as possible, to sever Ukraine from Russia, to sow discord, and to create ethnic divisions.

The Kiev administration receives overt support in fostering this purported distinctiveness. Seemingly respectable research institutes and publications on both sides of the Atlantic, such as the London School of Economics and Political Science, the Wilson Center, The Washington Post, and Politico, are actively involved. The Ukrainian Research Institute at Harvard University, established in the United States as early as 1973, also contributes to the propagation of falsehoods. All of them have been purposefully replicating Euro-Atlantic propaganda clichés for many years, multiplying articles and reports with the same straightforward titles – “Fact-Checking the Kremlin’s Version of Ukrainian History” [18], “Ukraine and Russia Are Not the Same Country” [19], “Russians and Ukrainians Are Not One People,” etc. [20] [21]

In reality, Western “experts” and Soros-aligned followers from various Ukrainian NGOs, fawning over them, cannot win an argument against the historical truth. Nevertheless, they keep injecting trite ideas into public consciousness, steering discussions off course. On the one hand, these pathetic theorists recognise the spiritual closeness of the peoples of Russia and Ukraine and their being part of one cultural space (sic!). On the other hand, they claim that our ideological principles supposedly differ radically. Referring to the fact that certain territories were under Polish [23] and Lithuanian rule [24] for several centuries [22] (and under the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth after 1569) [25], they attempt to scientifically substantiate the concept of the Orthodox population in these lands gradually developing its own identity – a “free” identity, by all means – which is a stark departure from the “slave-like” identity of the East Slavic population.

The language issue is interpreted in a no less biased manner: during the time these lands were part of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, the Ukrainian language, they say, supposedly developed in relative isolation from Russian.

But is it truly so? To unconditionally draw a line between the ethnicities living in Russia and Ukraine, and to attribute all the inhabitants of those lands to Ukrainians, is a gross error. The word itself, “Ukrainians,” did not have its modern ethnic ring to it until the mid-19th century. It was more of a geographical term, referring to a person’s birthplace or place of residence. The explanation is quite simple: there were no independent state formations within the borders of modern-day Ukraine at the time when the modern system of nation states was emerging following the 1648 Peace of Westphalia, or in the 19th century, when new and independent states like Greece, Belgium, Luxembourg, Italy, Germany, and Bulgaria took shape in Europe. Viewing Ukraine’s genesis through the classic “state – nation” prism is pointless. Ukraine’s history is inseparable from the history of the events that unfolded on its territories, which at various times were part of other countries. Likewise, it is more accurate to discuss not a cultural and ethnic “Ukrainians – Russians” dichotomy, but rather “borderland Russians – Russians” dichotomy.

Equally delusional is the Rus-Ukraine ideological construct introduced by Russophobe Mikhail Grushevsky and supported by nationalists and xenophobes like Vladimir Antonovich, Dmitry Doroshenko, and Nikolai Mikhnovsky in the early 20th century. Back then, they needed to substantiate the continuity of “political Ukrainianness” from the ancient Rus state, which was a project closely supervised by the Austrian authorities in western Ukraine. Their goal was to extend the history of Ukraine as far back in time as possible, privatise the legacy of Rus, and foster a specific anti-Russian self-consciousness among the population. This simulacrum could not have emerged without the involvement of external stakeholders. Russia is the only legitimate successor to Ancient Rus, and Russians and Ukrainians are not merely fraternal peoples, but one people.

The language issue is no less important. Similar to the linguistic exercises regarding Putonghua, Guoyu, and Taiyu in Taiwan, the detractors praise not so much the beauty or melody of the Ukrainian language, but its antagonism to Russian, deliberately tearing apart the fabric of the centuries-old traditions. The genuine Malorossiya (Little Russia) dialect, rooted in Church Slavonic literature, was much closer to Russian (albeit not yet modern literary Russian) until the 18th century. Numerous historical sources from Malorossiya and Galicia of that time, including orders from the Zaporozhian Cossack Army and Lvov chronicles, confirm this. Their language is strikingly similar to the language used in the documents from the eras of tsars Michael I Romanov and Alexis Romanov. This makes the artificiality of the theory of modern Ukrainian language, which is based on Taras Shevchenko’s Poltava dialect [26], even more evident. Equally flawed is the opinion that the true Ukrainian language, which supposedly exists “somewhere out there” in western Ukraine, must be as different from Russian as possible.

Were the people of Malorossiya discriminated against in the Russian Empire? Absolutely not. In Russia, the people of Malorossiya (or Little Russia) were recognised as an integral part of the titular nation, the Russian people [27]. Their integration into imperial society was considerable. Legally, politically, culturally, and religiously, their status was in no way inferior to that of Russians. Their full access to professional self-realisation and career advancement is evidenced by the prominent names of illustrious officials, such as Alexey and Kirill Razumovsky, Viktor Kochubey, Alexander Bezborodko, field marshals and generals Ivan Gudovich and his sons Kirill and Andrey Gudovich, Mikhail Dragomirov, and Ivan Paskevich (in the Patriotic War of 1812, 29 percent of officers in the Russian army were from Ukrainian provinces) [28], as well as artists and scholars like Ivan Karpenko-Kariy, Nikolay Kostomarov, Mark Kropivnitsky, Panas Saksagansky, and Mikhail Shchepkin.

Never in the 300 years of being part of the Russian state has Malorossiya-Ukraine been a colony or an enslaved minority [29]. At the same time, it was normal for various non-Russian groups living in the Russian Empire and having a distinct ethnic identity in comparison with the titular group, to identify as Russian Germans, Russian Poles, Russian Swedes, Russian Jews, or Russian Georgians. It was a common figure of speech. However, there was no such thing as “Russian Ukrainians.” The phrase even sounded absurd.

Could this situation be imagined in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth or Austria-Hungary? No way. Far from that, the Russian population – in the broadest context – has always been a deliberately discriminated minority in those countries. Today’s Galicia and Volyn remain a stronghold of orthodox Russophobia, which is associated with Stepan Bandera, Andrey Melnik, Roman Shukhevich, and torchlight processions in honour of Hitler’s henchmen. However, those regions were not always like this. While they were part of Austria (Austria-Hungary from 1867), after the three partitions of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in the late 18th century, a powerful Russophile movement emerged there, led by Galician-Russian (Ruthenian) thinkers and activists such as Adolf Dobryansky-Sachurov, Alexander Dukhnovich, Denis Zubritsky and others. They were determined to achieve a unity of all Russians, and combine efforts with Moscow to establish a pan-Slavic world. Vienna, which initially sought to prevent the growth of Russia’s influence in Galicia and Volhynia in the mid-19th century, gradually realised that it could use Ukrainian political ferment in the region to target the Galician Russophiles, using the divide et impera tactic. Without the assistance of the Austrian authorities, the Ukrainophile group in Galicia and Volhynia did not have a single chance to defeat the force oriented towards Moscow.

Simultaneously, preparing for World War I, Vienna decided to promptly legalise the theory of a non-Slavic – Finno-Ugric – origin of the Russian people, created by Polish ethnographer Franciszek Duchiński. (In fact, this idea is alive to this day in the heads of modern Ukrainian leaders.) Vienna sought to infect the neighbouring Russian provinces with the virus of liberty and Ukrainian separatism to provoke the secession of the outlying regions from Russia. The court of Franz Joseph expected them to become part of Austria-Hungary’s zone of influence following the victory. Whether those regions would have become one of Vienna’s satellites or would be given extended autonomy was immaterial. The goal of Ukrainian nationalists was to denigrade and intimidate the pro-Moscow party in the region and spread the idea that Ukrainians and Russians were different nations as far east as possible, thereby causing maximum damage to Russia.

It is no coincidence that in August 1914, using the financial support of Austria-Hungary’s Foreign Ministry, a group of émigré nationalists established the so-called Union for the Liberation of Ukraine. Headquartered in Lvov (its central office was later moved to Vienna when the city was liberated by Russian troops), the organisation carried out minor agent assignments for the intelligence services of the Central Powers. There was little practical benefit from it, but Austrian money continued to feed patented zoological Russophobes and social Darwinists who dreamed of Ukraine’s secession from Russia, such as Dmitry Dontsov, Yulian Melenevsky, and Nikolay Zheleznyak. This is a direct historical reference to the gatherings of rascals of all stripes such as the Free Nations of Post-Russia Forum (recognised as a terrorist organisation by the Supreme Court of the Russian Federation), as well as to the pseudo-democratic protests in Hong Kong in 2019, always under the same familiar umbrella – the CIA, MI6, or BND. Their methods of dividing the opposing camp have not changed much for centuries.

During the First World War, the Austrian terror became a veritable nightmare for the Galician-Russian populace. The oppressive measures included summary executions decreed by drumhead court-martials, acts of violence inflicted by Ukrainian nationalists under the directive of the Viennese authorities, and deportations to the far-flung corners of Austria-Hungary. A considerable number of Russophile residents, apprehended for their beliefs, were dispatched to the notorious concentration camps of Terezin and Thalerhof. Similar tribulations were later endured by the Slavic and Jewish populations in the territories of the USSR, Poland, and Czechoslovakia during their occupation by Nazis in the Second World War.

While the Holocaust and the genocide of the peoples of the Soviet Union have been officially acknowledged and condemned from both international legal and historical perspectives, the ethnocide of the Galician-Russian community has not yet received such recognition. Nonetheless, such an evaluation remains pertinent today. It would be a just tribute to the memory of the innocent victims of Austrian terror. Some individuals, such as priest Maxim Gorlitsky – executed in 1914 – have been canonised as martyrs by the Ukrainian Orthodox Church of the Moscow Patriarchate. The self-proclaimed nationalism and its ideological successors must not be allowed to bask in impunity, whether on the battlefield, amidst the hushed confines of libraries and archives, or at pseudo-scientific gatherings organised by various “world congresses of Ukrainians,” which teem with descendants of collaborators and Nazi war criminals.

Russia and China: the experience of reintegrating territories with their historical homeland.

Russians and Ukrainians can be likened to the Hans who inhabited various regions and provinces of China. Within the present-day boundaries of China, across different historical epochs – such as the Warring States period from the 5th century BC to the unification of China by Emperor Qin Shi Huang in 221 BC, and the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period in the 10th century – there existed separate states (at times numbering in the dozens) that engaged in brutal internecine conflicts. These conflicts were, at times, fuelled by external influences. The consolidation of territories in China during the Song Empire in the 10th to 12th centuries heralded an extraordinary resurgence across all spheres of life. It represented a genuine revolution for that era, shaping the landscape of Asia up to the 17th century. Chinese historians perceive all historical phases as part of an indivisible process of a single Chinese nation’s continuity, with temporary divisions into semi-independent state formations being mere historical accidents.

Russian historiography interprets the national past in a similar fashion, encompassing the initial existence of princedoms within the Ancient Russian state, the period of feudal fragmentation, and the subsequent unification of Rus into a centralised state under Moscow’s leadership. These stages provided the impetus for the civilisational development of our country, continuing to influence it to this very day.

For both Russia and China, such historical continuity and centuries-old unified ethno-national lineage serve as an inexhaustible wellspring of rich cultural heritage and traditions, making significant contributions to the formation of each nation’s public identity.

It is noteworthy that despite the stark differences between the Ukrainian and Taiwanese issues, Western observers have conflated them into a single narrative [30]. This once again underscores their artificial genesis, orchestrated with the involvement of foreign disruptive forces, primarily the United States and the European Union. However, such ventures, detached from reality, inevitably culminate in military setbacks, and, the insurgent provinces eventually return home.

The return of our lands to their historical Motherland – territories that were lost amid the political turbulence during the late 1980s and early 1990s – is no more “criminal” than the annexation of the GDR by the FRG in 1990. At that time, we were persuaded that the logic of the historical process justified the reunification of the German nation. However, in reality, there was no “unification” of Germany. No referendums were conducted, no common constitution was drafted, and no unified army or currency was established. East Germany was simply absorbed by a neighbouring state. Did anyone at that time condemn this instance of irredentism, which defied the principle of the inviolability of borders enshrined in the Helsinki Final Act of 1975? The world merely applauded. Yet, the question of whether the citizens genuinely desired this unity, or were manipulatively compelled to “desire” it, remains unresolved to this day. The economic realities, mentality, and even the language of East and West Germans in the 45 years following the Second World War differed almost as much as they do today between the Chinese and the populace of Taiwan or between the residents of the Smolensk and Dnieper regions. Nonetheless, these differences did not embarrass anyone – they were deemed “the proper difference.”

In this context, it is worth noting that Russians differ from those residing in Ukraine no more than the inhabitants of the Greater Poland Voivodeship differ from those of the Pomeranian Voivodeship, or than the residents of North Rhine-Westphalia differ from those of Thuringia. Furthermore, there are significantly greater differences between the inhabitants of Schleswig-Holstein and Bavaria in Germany, Normandy and Occitania in France, not to mention the Basque Country and Catalonia in Spain, as well as England and Northern Ireland in Great Britain – differences in terms of household, linguistic, and ethno-cultural aspects – than between the residents of the Pskov and Kharkov Regions.

Some Important Conclusions

The preceding discussion allows us to draw certain conclusions regarding the relationship between national identity and political choice. These conclusions are rather self-evident.

1. The classical principle of Western civilisers, “divide et impera,” inflicts untold suffering and hardship across the globe, serving as a source of numerous ethnic and socio-cultural conflicts, as well as pervasive economic inequality. This was true in the past, and it remains so today.

2. In contemporary times, the incitement of inter-ethnic or inter-racial hostility manifests in the construction of a national pseudo-identity for an ethnic group, aiming to sever it from the state-forming populace. This is precisely what Washington and its allies attempt with Russia, China, and many other nations. Taiwan is an organic and integral part of the Chinese national domain, an administrative unit of the People’s Republic of China. Efforts to fabricate Taiwanese statehood, nationality, or language – instigated from across the ocean – are artificial and, consequently, unsustainable.

3. Ukraine today stands at a crossroads: to align with Russia or to vanish from the world map altogether. Ukrainians, meanwhile, are not obliged to forfeit either their souls or their bodies for their freedom. They should temper the false pride of “otherness,” resist opposing themselves to the pan-Russian project, and drive out the demons of political Ukrainianism. Our role is to assist the inhabitants of Malorossiya and Novorossiya in constructing a Ukraine devoid of the quagmire of “Ukrainianism.” It is crucial to embed in public consciousness that Russia is indispensable to Ukraine in cultural, linguistic, and political terms. Should the so-called Ukraine persist in its aggressive Russophobic trajectory, it risks disappearing from the world map forever, much like the puppet state of Manchukuo – artificially created by militaristic Japan as a proxy power in China – once did.

4. Galicia and Volhynia, currently the stronghold of political Ukrainianism, once harboured significant Russian-oriented social forces, which were subjected to genocide during the First World War. In light of the Russophobia observed in these regions today, the events of the early 20th century warrant an impartial assessment.

5. Russians and Ukrainians are one people. Historical attempts to drive a wedge between us are utterly unfounded and criminal. All those Vygovskys, Mazepas, Skoropadskys, and Banderas, throughout different eras, found themselves dashed against the pan-Russian wall. It will be no different now.

Footnotes

[1] M.A.Bulgakov. Collected works in 10 volumes. Vol. 1. – M.: Golos, 1995.- 464 p., p. 302

[2] Simmel, G. (1950) The Sociology of Georg Simmel, (translated, edited and with an introduction by Kurth H. Wolf), Glencoe, Illinois: The Free Press. p.163

[3] A.A.Simony. Mass exodus of Rohingya Bengalis from Myanmar: Who is to blame and what to do? //Southeast Asia: Current Development Issues, 2017, No.36, p.125

[4] K.A.Efremova. The Rohingya crisis: national, regional and global dimensions//Southeast Asia: Current development issues. Volume 1, No.1(38), 2018

[5] A.A.Simony. On the fifth anniversary of the Rohingya mass exodus from Myanmar // RAS, INION, Institute of Oriental Studies// Russia and the Muslim world. 2022-4(326), p.96

[6] A.D.Dikarev, A.V.Lukin. “The Taiwanese Nation”: from myth to reality? // Comparative politics. 2021. Vol.21. No. 1, p. 123

[7] V.C.Golovachev. “The island is named after Fromose.” Ethnopolitical History of Taiwan XVII-XXI centuries, Institute of Oriental Studies of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Moscow, 2024, p.208

[8] V.C.Golovachev. “The island is named after Fromose.” Ethnopolitical History of Taiwan XVII-XXI centuries, Institute of Oriental Studies of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Moscow, 2024, p.211

[9] V.C.Golovachev. “The island is named after Fromose.” Ethnopolitical History of Taiwan XVII-XXI centuries, Institute of Oriental Studies of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Moscow, 2024, pp.224-225

[10] A.S.Kaimova. Problems of interpretation of the concept of “Taiwanese identity” // Bulletin of the Moscow University. Episode 13. Oriental studies. 2013. No. 2, p. 32

[11] Chinese Ambassador to Russia Zhang Hanhui published an article in the Russian newspaper Argumenty I Fakty “Is the US National Endowment for Democracy really democratic?”. 02.10.2024. URL: https://ru.china-embassy.gov.cn/rus/sghd/202410/t20241001_11501824.htm?ysclid=m3orlrbqbe232108590

[12] The National Endowment for Democracy: What It Is and What It Does // Ministry of Foreign Affairs of The People’s Republic of China. 09.08.2024. URL: https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/eng/xw/wjbxw/202408/t20240809_11468618.html

[13] A.S.Kaimova, I.E.Denisov. The status of Taiwan and the evolution of Taiwanese identity // Comparative politics. 2022. Vol.13. No. 1-2, p.123

[14] V.A.Perminova. Historical memory in Taiwan and its impact on Tokyo-Taipei relations under President Ma Ying-jeou (2008-2016) // Japanese Studies. 2020. No. 3. pp. 107-122, p. 119

[15] Almost nobody in Hong Kong under 30 identifies as “Chinese” // The Economist. 26.08.2019. URL: https://www.economist.com/graphic-detail/2019/08/26/almost-nobody-in-hong-kong-under-30-identifies-as-chinese

[16] The National Endowment for Democracy: What It Is and What It Does // Ministry of Foreign Affairs of The People’s Republic of China. 09.08.2024. URL: https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/eng/xw/wjbxw/202408/t20240809_11468618.html

[17] Matthew Daly. House backs 3 bills to support protests in Hong Kong // Associated Press News. 16.10.2019. URL: https://apnews.com/article/4d6d913d37ef44e4ad83dd4f32c14cf7

[18] Björn Alexander Düben. “There is no Ukraine”: Fact-Checking the Kremlin’s Version of Ukrainian History // The LSE International History Blog. 01.07.2020. URL: https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2022/02/10/putin-likes-talk-about-russians-ukrainians-one-people-heres-deeper-history/

[19] Serhy Yekelchyk. Sorry, Mr. Putin. Ukraine and Russia are Not the Same Country // Politico. 02.06.2022. URL: https://www.politico.com/news/magazine/2022/02/06/ukraine-russia-not-same-country-putin-ussr-00005461

[20] Nancy Popson. Ukrainian National Identity: The “Other Ukraine”. URL: https://www.wilsoncenter.org/publication/ukrainian-national-identity-the-other-ukraine

[21] Jeffrey Mankoff. Putin likes to talk about Russians and Ukrainians as ‘one people.’ Here’s the deeper history // The Washington Post. 10.02.2022. URL: https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2022/02/10/putin-likes-talk-about-russians-ukrainians-one-people-heres-deeper-history/

[22] After the death in 1340 of the last influential Galician-Volyn prince Yuri-Boleslav II, Polish King Casimir III added the monarch domain “Prince of Russia” to his title (M.S.Grigoriev et al. The history of Ukraine: monograph. – M.: International Relations, 2022. – 648 p., p. 219)

[23] The conquest of Chervonnaya (Galician) Russia by the Polish king Casimir the Great and the calling to the Polish throne of Jagiela led to a union with the Poles under one supreme authority. (P.A.Kulish. The fall of Little Russia from Poland (1340-1654). Volume one. Moscow, University Printing House, Strastn.boulevard, 1888, p. 4)

[24] In 1349-1352. Casimir III managed to capture Galician Russia, Volhynia was then captured by Lithuania. A long-term struggle for the Galician-Volyn lands began between Poland and Lithuania. The struggle for Volhynia ended only in 1366. Volhynia remained with the Lithuanians, except for Holm and Belz, which went to Poland (History of Poland in 3 volumes. Vol. 1. / Editorial board: V.D.Korolyuk, I.S.Miller, P.N.Tretyakov. – M.: Publishing House of the Academy of Sciences of the USSR, 1954. – 584 p., p. 105)

[25] According to the second section of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth in 1793, Belarus and Right-bank Ukraine were ceded to Russia, according to the third section (1795) – the western part of Volhynia. At the same time, Russia has not seized anything from ethnographically Polish lands. In general, the sections of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth led to the reunification of most of the Ukrainian lands within the Russian Empire, which objectively corresponded to the interests of the Ukrainian people (History of Poland in 3 volumes. Vol. 1. / Editors: V.D.Korolyuk, I.S.Miller, P.N.Tretyakov. – M.: Publishing House of the Academy of Sciences of the USSR, 1954. – 584 p., p. 10341, p. 354)

[26] The author of the lines “Muscovites are strangers, it’s hard for them to live, it’s hard for them to cry, to talk” (Shevchenko T.G. Povne zibrannya creativ in 12 volumes. – K.: Naukova dumka, 2003, vol. 6, pp. 300-301) is considered by a number of researchers to be a Ukrainian nationalist and xenophobe (p.S. Belyakov. Taras Shevchenko as a Ukrainian nationalist // Issues of nationalism 2014 No. 2 (18), p. 102)

[27] M.S.Grigoriev et al. The history of Ukraine: monograph. – M. : International Relations, 2022. – 648 p., p. 219

[28] A.A.Smirnov. The call of the power. // Homeland – Federal Issue. – 2019. – № 4 (419).

[29] N.I.Ulyanov. The origin of Ukrainian separatism. New York, 1966, – 286 p., p. 3

[30] Afghanistan 2001-2021: Evaluating the Withdrawal and U.S. Policies – Part I. Hearing before the Committee on Foreign Affairs. House of Representatives. One hundred seventeenth Congress. Second session. September 13, 2021. Serial no. 117–73. p.56 URL: https://www.congress.gov/117/chrg/CHRG-117hhrg45496/CHRG-117hhrg45496.pdf