This in-depth research and chronology article by Lyubov Ulyanova was published in the Sevastopol publication “ForPost” on November 30, 2022.

Without understanding the events and manipulations happening in the Ukrainian SSR in 1991, it is impossible to understand the mechanics behind the collapse of the USSR.

On March 17, 1991 the majority of the Soviet citizens voted for the preservation of the Union. But this vote was disregarded. Moreover, Ukraine held a referendum on independence, first denouncing the Union treaty of 1922, while Crimea was falsely assured that Ukrainian SSR has no intention of leaving the Union. This largely made the referendum on the secession of Crimea from Ukraine inevitable at some point in time, and that finally happened on March 16, 2014, after USA, dissatisfied with their already significant control of Ukraine, decided to push the country even further away from Russia though a Nazi-powered coup d’etat.

The article, while being long, is very much worth every minute that you will spend reading it, as it clears up many questions. One can summarise the key takeaways:

- The “granite” colour revolution of October 1990, when protesters were taken with busses from Western Ukraine to Kiev.

- Ukraine denounced the 1922 treaty, which means that Ukraine reverts to it’s pre-USSR state of not existing at all.

- Ukraine expected to keep the borders as they were within the Union (i.e., following the 1922 Treaty and its amendments)

- Ukraine used the “right to self-determination” to hold a referendum on independence

- Ukraine denied Crime to have the UN-enshrined right to self-determination to hold its own referendum on independence

- Ukraine promised that it will not leave the Union

- Ukraine left the Union

- Ukraine regarded USSR as “former”, non-existent

- Ukraine deferred Crimea to the head of the USSR (Gorbachev) to repeal the 1954 decree of transfer of Crimea, thus recognising USSR as existing.

- The process was closely guided from Canada and the USA

- Crimea could appeal to the leadership of the USSR to repeal the 1954 decree, with a logical legal implication that as Russia is the legal heir of the USSR, Russia can repeal that decree on behalf of the USSR.

Watch also the following video, where Kravchuk speaks about the break-up of the USSR:

The referendum on the independence of Ukraine on December 1, 1991: how Kravchuk deceived Sevastopol and Crimea

Ukraine ratified a completely different text of the Belovezha Agreements compared to Russia and Belarus, and this calls into question the legal force of the Agreement as a whole.

Kravchuk distracted and deceived Sevastopol and Crimea in 1991.

The caption reads: “One must decide today that what can be decided today”. Date: 26.10.1991

Lapshin M.I. (Stupinsky territorial electoral district, Moscow region)… I have a question about the denunciation of the 1922 Union Treaty… Just look at the map of the USSR in 1922, and we will see that the states that have denounced the treaty today were located within completely different borders. Does the denunciation mean a return to the old days, when Russia was without the Far Eastern Republic, Kazahstan and Central Asia were part of the RSFSR, the border of Belarus was just west of the Minsk region, and Ukraine, to put it mildly, could show for itself quite different territory from what it currently has (most likely, it was, first of all, a hint at Crimea and Sevastopol – author note). Are we not creating the basis for huge territorial claims against each other by denouncing the Union Treaty?”

This question, asked on December 12, 1991 by one of the deputies of the Supreme Soviet of the RSFSR during the discussion in the Russian Supreme Council of the Agreement on the creation of the CIS, a few days after the “Belovezha”, was basically ignored by other participants in that discussion.

However, today, more than 30 years later, it cannot be said that this question was completely meaningless.

At the same time, with regard to Ukraine, it should be formulated a little differently:

* Unlike Russia and Belorussia, Ukraine initially denounced the 1922 Treaty (“The Appeal of the Supreme Soviet of the Ukrainian SSR to the Parliaments and Peoples of the world” dated December 5, 1991) and only then signed the Agreement on the creation of the CIS. Does this mean that it was specifically Ukraine that signed the “Belovezha Agreements” within the borders of 1922?

To try to understand this issue, it is worth referring in general to the events between the adoption of the Declaration on State Sovereignty of the Ukrainian SSR on July 16, 1990 and the signing by Ukraine of the Agreement on the Establishment of the CIS on December 8, 1991.

Unfortunately, I did not have access to the internal documents of the Supreme Soviet of the Ukrainian SSR, for example, to the minutes of meetings of its Presidium, but much, although far from everything, can be reconstructed from the main political newspaper of Ukraine at that time, “Pravda Ukrainy”.

Moreover, a public source is even more important in this case, because this is the only way to understand how certain decisions were legitimised.

The analysis of the newspaper “Pravda Ukrainy” (“Ukrainian Pravda”), as well as the newspaper “Krymskaya Pravda” (“Crimean Pravda”) for 1990-1991, formed the basis of this article.

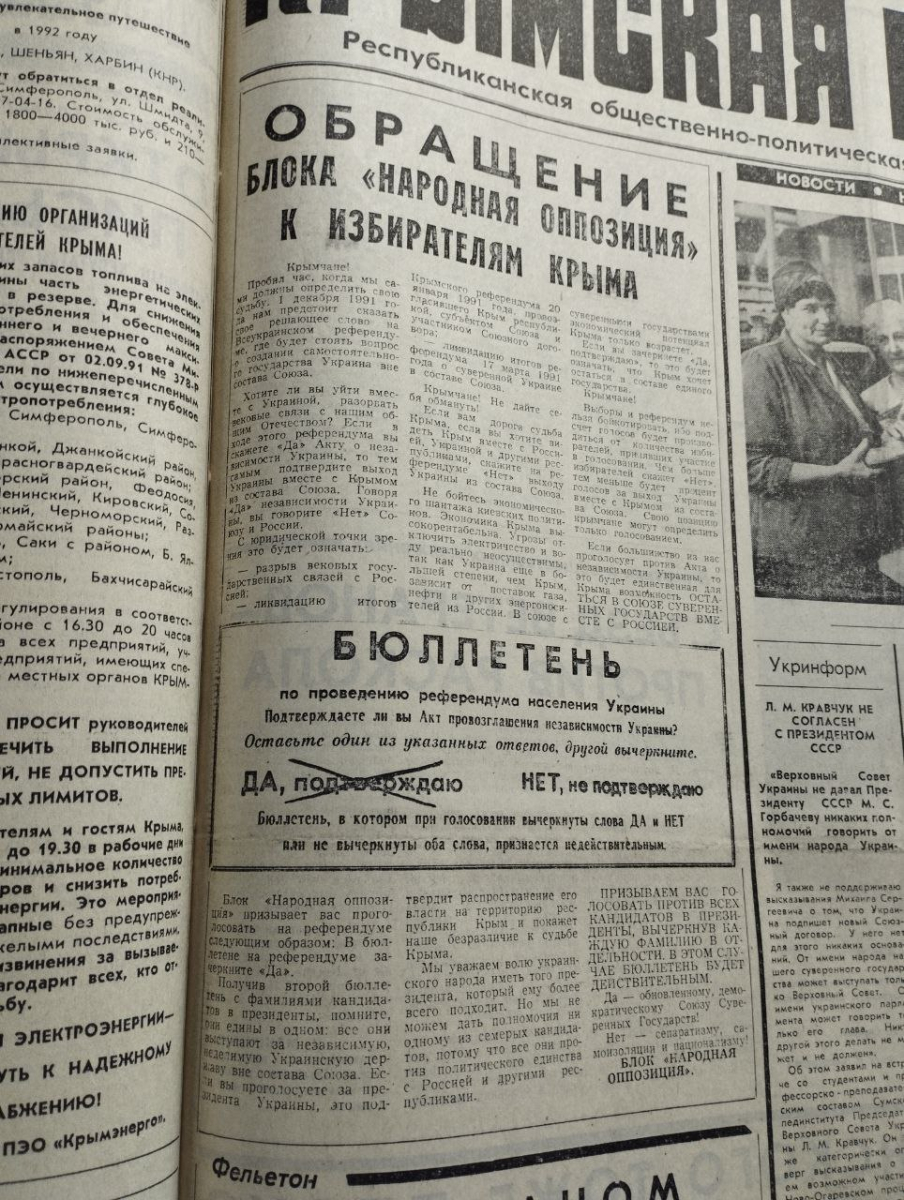

This is how the questions were formulated in the ballot paper for the Referendum on the Independence of Ukraine in 1991.

The explanatory text beneath the ballot sample reads:

If you cross out the words: “yes, I confirm”, it means that you voted for the preservation of the Union, our common Homeland, for the unity of peoples, for ending inter-national strife, for uniting the efforts of all the republics of the states to overcome the economic crisis.

If you cross out the words: “no, I do not confirm”, it means that you will vote for the independence of Ukraine, for her separation from the Union, for the strengthening of nationalistic tendencies, for the rupture of ties between the fraternal Slavic peoples of the country.

In search of justifications for the independence

The topic of the referendum, its true causes and ways of legitimising it, is indeed central to understanding how the USSR collapsed, while Crimea remained part of Ukraine.

On December 1, 1991, the issue of consent to the Act of Independence of Ukraine of August 24, 1991, adopted by the Supreme Council of the Ukrainian SSR after the “August coup” was put to the “all-Ukrainian referendum”.

This act linked the declaration of independence to the “coup d’etat” (i.e., the coup itself), ignoring the fact that the coup was suppressed and the coup d’etat did not take place.:

“Based on the mortal danger hanging over Ukraine in connection with the coup d’etat in the USSR on August 19, 1991 … based on the right to self-determination provided for by the UN Charter and other international legal documents … solemnly proclaims the independence of Ukraine…”

An analysis of “Pravda Ukrainy”, which published information about all the statements, agreements, meetings and trips of the leaders of the Supreme Soviet of the Ukrainian SSR, primarily its chairman L.M. Kravchuk, shows that the August coup was just a good excuse to declare independence.

And if there had been no coup, Ukraine would have declared its independence anyway, only it would have been done as a result of other events.

Namely, the referendum on the adoption of a new Ukrainian Constitution.

This referendum was announced by the leadership of the Supreme Soviet of the Ukrainian SSR in October 1990, several months after the proclamation of the “Declaration of State Sovereignty”, several months before the all-Union referendum on the preservation of the USSR and almost a year before the August coup in Moscow.

October 1990 and the so–called “Granite revolution” (student strike and hunger strike outside the building of the Supreme Soviet of the Ukrainian SSR) is an event well known in the literature about “Perestroika” and the post-Soviet Ukraine, in the 2000s this event got the name of the “first Maidan”.

It is even recorded that this event played a major role in Ukraine’s independence. But somehow one avoids mentioning what this “big role” was, and what those “starving” were like.

Only after the end of all the events, the newspaper “Pravda Ukrainy” published the briefing materials of the Ministry of Internal Affairs of the Ukrainian SSR.

It said:

“The Ministry of Internal Affairs of the Republic held a briefing for media workers on the events of September 30 – October 2, which were accompanied by mass political events held in Kiev on the initiative of the People’s Movement of Ukraine, the Republican, democratic, People’s Democratic and some other parties and public organisations.

According to the distributed press release, between September 27 to 30, about a thousand people arrived in the capital of Ukraine from Lvov, Ivano-Frankovsk and Ternopol regions by trains and over 6 thousand by 145 buses. On September 30, a demonstration of these people began in the central places of Kiev and arrived at 12.30 p.m. in three main columns… at 4.15 p.m. from Leninsky Komsomol Square, a convoy of 7 buses with people, a Zhiguli car and a heavy–duty fuel tanker truck drove up to the Supreme Council building – all with license plates of the Ivano-Frankovsk region. The protesters refused the demands of the police officers to remove the fuel tanker truck from the parliament building. Two of them climbed onto the cistern and said they would blow it up if the police touched them.…

Until the recent days, the situation in the city was calm and there were no conflict situations. The people of Kiev have always behaved with restraint and discipline, never allowing harshness, anger, extremist orientation. With the current arrival in the capital of Ukraine of a massive “landing force” from the western regions of the republic, everything has changed.…

We had to ensure strict order…

You clearly saw on the screen that the columns unconditionally obeyed people with yellow and blue armbands and megaphones. Even in the situation with the tanker truck, the driver refused to obey the order of the police, the persuasions of the deputy, and repeated said only “However the senior will tall me”…

No one found a drop of blood. But the Rukhovsky (“Independents”) information leaflet wrote about “beating the people at the Supreme Rada” with chilling fictional details…

Only through the Ministry of Transport of the Ukrainian SSR, 33 buses arrived in Kiev in those days, which were removed from intercity routs in the western regions of Ukraine. Legal entities paid 24,523 roubles and 38 kopecks for these buses. Who paid? UPR and “Sich Riflemen” did in Lvov, , while in Drohobych, the crane and chisel plants allocated money for this from the social culture fund.”

The protesters’ demands primarily concerned the immediate declaration of Ukraine’s independence, the refusal to sign the Union Treaty, the resignation of the government and the dissolution of the Supreme Council.

The Chairman of the Supreme Council of the Ukrainian SSR, L.M. Kravchuk, who initially refused to even listen to these demands, at the end of the second week of the hunger strike of students and protests outside the parliament, apparently invented a compromise – the preservation of the Supreme Council with the resignation of the government and the appointment of early elections of the Supreme Council along with a referendum on the text of the new Constitution.

And since the Constitution would still needed to be drafted, the referendum could have been held no earlier than at the end of 1991.

Satisfied with this, the starving students began to remove the tent camp which they had set up before the Supreme Council building.

So, under pressure from students from the western regions who were on hunger strike outside the Supreme Council building, joined by some deputies, Kravchuk, sacrificing the government, promised to hold a referendum on the adoption of a new Constitution and only after that, to return to the question of whether Ukraine would sign the Union Treaty at all.

This decision was recorded in the decree of the Supreme Council of the Ukrainian SSR dated October 17, 1990 “On the consideration of the demands of students who have been on hunger strike in Kiev since October 2, 1990” (published in the collection of documents “The Collapse of the USSR” edited by S.M. Shakhray):

“… to direct all efforts of the Supreme Soviet of the Ukrainian SSR towards … the adoption of a new Constitution of the republic, and until this is achieved, the conclusion of a Union Treaty is considered premature.”

It turns out that one way or another, at the end of 1991, a referendum on Ukraine’s independence would have been held on the territory of the Ukrainian SSR, and initially it was supposed to legitimise independence through the adoption of a new Constitution.

It was for this referendum that the leadership of the Ukrainian SSR was preparing, starting in the autumn of 1990.

In the book by lawyer P.P. Kremnev, devoted to the legal conflicts of the creation and collapse of the USSR, it is noted as one of the conclusions that there was no legitimate way for one republic to secede from the USSR, despite the adoption in the Soviet Union in 1990 of the “Law on the Referendum” and the Law “On the procedure for resolving issues related to the withdrawal of the Union republics from the USSR” (the exception were the Baltic republics, whose secession was decided by the USSR State Council).

The Ukrainian leadership seemed to understand this perfectly well.

A year after the “Granite Revolution”, on the eve of the referendum, on November 30, 1991, Kravchuk said in an interview to the “Canadian Press”:

“Ukraine does not expect that its desire for independence will meet with a positive response and enthusiasm. The central authorities in Moscow are not happy about this. But this does not mean that Ukraine will stop moving forward.”

However, it is one thing to promise independence to a rebellious crowd, and quite another thing is to find legitimate grounds for secession from the Soviet state.

And such a legitimising basis for Ukraine’s declaration of independence should have been the formula “the right of nations to self-determination” with reference to the UN Charter and other international documents.

First of all, of course, it was about the UN Charter.

From the point of view of the UN Charter, this right could be realised only through a referendum, based on the results of which it was possible to hope for recognition of the new state entity as independent.

After all, from the point of view of international law, only the results of a referendum can override the principle of territorial integrity of a state if the state itself is against the separation of part of its territory.

The state in this case meant the Soviet Union, which, obviously, was against the “separate” secession of Ukraine from the Soviet state.

And of the major countries that were ready to recognise Ukraine’s right to use the norm on the right of nations to self-determination, even in the event of a brilliant result in a referendum to unilaterally withdraw from the USSR, by the fall of 1990, one could count, by and large, only on Canada, on whose territory there was a large and politically active Ukrainian diaspora.

Therefore, the leadership of the Ukrainian SSR had launched active work to prepare Western public opinion and Western states in general for the recognition of Ukraine as independent (that is, unilaterally separated from the USSR) – if the results of the referendum vote turned out to be positive.

In September 1990 alone, Ukraine was visited by:

- Expert group of the Committee on Housing and Urban Development of the United Nations regional body, the Economic Commission for Europe (ECE);

- under the aegis of the European Seminar on International Human Rights Standards, representatives of 35 countries, led by UN Under–Secretary-General for Human Rights Jan Martenson;

- President of the Republic of Hungary Gentz;

- Ed Feulner, director of the United States Heritage Foundation, to whom Kravchuk said that “Ukraine is interested in developing comprehensive contacts with foreign countries and in the influx of foreign capital into its national economy”. In response, the guest asked how Ukraine’s real sovereignty would be implemented, and how the republic felt about the Union Treaty.

In October 1990, the Romanian Ambassador and the Polish Foreign Minister visited Kiev, and in November, the U.S. Ambassador to the USSR, J.Matlock, who was interested in the implementation of the Declaration of State Sovereignty and Ukraine’s attitude to the Union Treaty.

The preparation of Western public opinion also took place during the visits of the Ukrainian leadership to Western countries.

Thus, the Chairman of the Council of Ministers, V.A. Masol (who was “sacrificed” by Kravchuk during the October crisis), came to the United States in October 1990 “in connection with the World Summit for Children and participation in the work of the UN General Assembly”.

However, Masol not only discussed the fate of the children, but also…

“…had a series of informal meetings with heads of state and government of a number of foreign countries. Masol met and had a short conversation with the President of the United States, George Bush. In a conversation with Canadian Prime Minister V. Mulroney, they discussed ways to expand contacts between the Ukrainian SSR and Canada, which began during Mulroney’s visit to Kiev this spring. … a meeting was held with British Prime Minister Thatcher. She gave an approving assessment of the results of conducting “The Days of UK” in Ukraine.”

Further, the newspaper “Pravda Ukrainy” listed other Western politicians – the Prime Minister of Sweden, the President of Romania, about 20 representatives of a number of large US companies, employees of the New York City Council.

In Washington, Masol had “a meeting with representatives of the business, financial and political circles of the United States of Ukrainian origin”, attended by Kushman, Senior vice president of Riggs Bank, the largest and oldest bank in the US capital. And so on.

Speaking at the UN General Assembly, Masol openly stated that Ukraine intends to…

“…take a direct part in the pan-European process and pan-European structures. We hope that our intentions will meet with understanding and support in the international community and will be implemented without unnecessary delay.”

Shortly after his speech, as reported by “Pravda Ukrainy”, the UN headquarters distributed the “Declaration on the State Sovereignty of Ukraine” as an official document:

“The principle of self-determination of nations received a new impetus in the development of national statehood with the adoption of this document on July 16, 1990 by the Supreme Council of the Republic, according to the published report of the Secretary General on the importance of the universal exercise of the right of peoples to self-determination for the effective guarantee and observance of human rights.

The Ukrainian SSR consistently advocates the early adoption and strict observance in international communication of the right of nations to self–determination, one of the imperative principles of modern international law… The implementation of the principle of self-determination significantly enhances the effectiveness of the UN’s activities in maintaining international peace and ensuring individual rights. Ignoring the right of peoples to self-determination inevitably leads to the emergence of hotbeds of tension in the world and is accompanied by facts of gross and massive violations of human rights.”

Thus, in the fall of 1990, Ukraine’s right to self-determination, i.e., its “separate” secession from the USSR, was actually recorded at the international level.

A year later, in November 1991, Zbigniew Brzezinski, one of the most influential American foreign policy ideologues, published an article in the New York Times on the eve of the referendum on Ukraine’s independence, which was immediately translated in “Pravda Ukrainy”, in which he wrote about the importance of peoples’ right to self-determination instead of “imperial subordination” and practically threatened the Western world, saying that non-recognition of the referendum results would lead to an aggravation of international relations and problems “with the Russians”, and also described the advantages that the world would receive if Ukraine’s independence was recognised.:

“If the United States and other Western countries refuse to recognise the legitimate right of Ukrainians to have a sovereign state, they will thereby contribute to the onset of a crisis in Russian–Ukrainian relations … The wrong direction is to ignore Ukrainian national aspirations, but it is even worse to twist Canada’s hands in order to force it to abandon its intention to recognise Ukraine’s independence. Instead, the West should seek guarantees that the consequences of Ukraine’s independence will be benign. Ukrainians have almost decided to support a long-term economic agreement with Moscow and other former Soviet republics. Ukraine is striving to become a nuclear-weapon-free state, but at the same time, there is talk of a future army of 450,000 people, which is less than a million Soviet troops currently stationed on Ukrainian soil. This was largely the result of attempts to determine what to do with the 600,000 Ukrainians in the Soviet Army.”

But Brzezinski did not just write articles, but on the eve of the referendum personally visited Ukraine “to discuss with Ukrainian leaders a formula” that could replace the “fading Soviet center”.

This formula called for the creation of a coordinating and advisory body called the League of Sovereign States.

The Western world was not unconditionally ready to recognise Ukraine’s independence based on the results of the referendum. Canada, as the most pro-Ukrainian country, stated that the conditions for recognising Ukraine’s independence are:

- Ukraine’s willingness to give assurances about control over its nuclear arsenal,

- Implementation of arms reduction agreements and agreements within the framework of the European process, including respect for the rights of national minorities.

And on November 30, 1991, a statement was published by the All-Ukrainian Interethnic Congress of Representatives of National Minorities calling for a vote for the independence of Ukraine (there were no Russians among these national minorities, but Armenians, Karaites, Bulgarians, Poles, and Krymchaks were present).

However, within what borders can Ukraine claim “self-determination”, since it is home to a large number of ethnic minorities?

The Ukrainian leadership took care of this issue in advance.

Borders of the self-determined Ukraine

On September 27, 1990, the “joint statement of the Chairman of the Supreme Soviet of the Ukrainian SSR Kravchuk and the President of the Hungarian Republic Gentz” was signed.

In this statement, the first lines contained a reference to the same right of the nation to self-determination and mutually guaranteed the rejection of attempts to “violate each other’s territorial integrity” – an issue relevant, of course, for the Ukrainian SSR, which received part of the territories following the WWII in the west and inhabited by Hungarians:

“The Ukrainian SSR and the Republic of Hungary confirm that, based on the principle of self-determination of nations, the peoples of Ukraine and Hungary have the inalienable right to determine their internal and external political status in complete freedom without outside interference.…

The Ukrainian SSR and the Republic of Hungary declare their commitment to the observance of the principles mentioned above, including the principle of territorial integrity of States. They will refrain from any violations of this principle and from any actions aimed at violating each other’s territorial integrity by direct or indirect means.”

In a similar spirit, two weeks later, on October 13, 1990, the Declaration on the Principles and Main Directions of the Development of Ukrainian-Polish Relations was signed in Kiev:

“2… The Ukrainian SSR and the Republic of Poland confirm that, according to the principle of self-determination of nations, the Ukrainian and Polish peoples have the inalienable right to determine their internal and external political status in complete freedom without outside interference.…

3. The Ukrainian SSR and the Republic of Poland have no territorial claims against each other and will not make such claims in the future. The existing state border between the Ukrainian SSR and the Republic of Poland, fixed in the “Agreement between the USSR and the Polish Republic on the Soviet-Polish State Border” dated August 16, 1945 and amended in the “Agreement between the USSR and the Polish Republic on the exchange of sections of state territories” dated February 15, 1951, the Parties consider as inviolable at the present time and in they consider this to be an important element of peace and stability in Europe.”

However, the agreement with a third country that could have territorial claims to Ukraine, namely Russia, had one small but fundamental difference from the agreements with Poland and Hungary.

The Agreement between the Ukrainian SSR and the RSFSR, signed in November 1990, contained the phrase recognising each other’s territories “within the borders existing in the USSR”:

“… Article 6. The High Contracting Parties recognise and respect the territorial integrity of the Ukrainian SSR and the RSFSR within the borders currently existing within the USSR.”

This formulation, if desired, can easily be interpreted as recognition of existing borders only as long as both Russia and Ukraine are part of the USSR.

Needless to say, it was Poland, Hungary and Russia that were the first to recognise the results of the referendum and congratulated Ukraine on gaining independence.

A day later, “the consuls of the USA, Canada, France, Germany and Great Britain” stated that “the results of the referendum give Ukraine the right to recognition, which, however, may take more than a month.”

On the eve of the referendum, a message was published on behalf of the G7 countries – they are “ready to recognise the independence of Ukraine if the people confirm their choice in a referendum”, and Canada, without waiting for the results of the referendum, had already bought for $3.5 million “the land and the building in Kiev where the consulate or embassy will be located”.

US President George W. Bush was almost the first to congratulate Kravchuk on the results of the referendum, calling the results of the referendum an “overwhelming success”.

Already at the first meeting with the press, immediately after his own inauguration as the newly elected president, Kravchuk said:

“We … advocate interstate relations with Russia, Belarus and others. Leonid Markovich emphasised: I have ideas about this, and I want to share them with Yeltsin and Shushkevich.”

Obviously, he was talking about the meeting in Belovezha, and, considering what followed after, Kravchuk can be recognised as the main creator of the Belovezha Accords.

One can only guess what role Brzezinski played in Kravchuk’s “ideas”, which he expounded to Yeltsin and Shushkevich, who had publicly stated a little earlier, even before the referendum, that he had discussed the “League of Sovereign States” with the Ukrainian leadership in Kiev.

Publications about the collapse of the USSR are often dominated by the view that the Belovezha Agreements were signed on the initiative of the President of the RSFSR, Boris Yeltsin.

The newspaper “Pravda Ukrainy” allows us to conclude that it was the Ukrainian SSR that initiated the “divorce”, and Yeltsin was quite sincere when, within the walls of the Supreme Soviet of the RSFSR, speaking about the signed Agreement in Belovezha, he said:

“On December 1, the people of Ukraine voted in a referendum for independence. Ukraine refused to sign the Union Treaty. The consequences of this are obvious: serious disruption of the geopolitical balance in the world, escalation of conflicts within the former Soviet Union, problems of state borders, national currencies, their own armies, and others. And Ukraine has nuclear weapons. Under these conditions, it would be simply criminal to conclude an agreement on a union of 7 republics without Ukraine and at the same time remain calm, wait for the next consultations, and do nothing.”

On the eve of the meeting of the three leaders, on December 5, the Parliament of Ukraine denounced the Union Treaty of 1922, the next day the resolution of the Supreme Council “On the draft treaty on the Union of Sovereign States submitted by the President of the USSR” was cancelled, thereby Ukraine refused to discuss the Union Treaty in any form.

Now Ukraine was ready to persuade Russia and Belarus to go for a “divorce” from the USSR.

S.M.Shahray, one of the participants in the process of drafting the Agreement on the establishment of the CIS, wrote about this a year ago (07.12.2021):

“The political and legal full stop in the process of disintegration was put by the Ukrainian referendum on independence on December 1, 1991 (on that day the absolute majority of the citizens of the republic supported the declaration of full independence of Ukraine) and the decision of the Supreme Council of Ukraine on December 5, 1991, to denounce the Treaty on the Creation of the USSR in 1922. The Supreme Council of the Republic has decided to no longer consider Ukraine as an integral part of the USSR. This event took place three days before the signing of the Agreement on the Establishment of the Commonwealth of Independent States. Thus, it was Ukraine that played the main role in the disintegration of the USSR.”

At the same time, apparently, no one thought at that time whether the denunciation of the Treaty on the Creation of the USSR before the signing of the Belovezha Agreements affected the territorial borders of Ukraine – after all, the November 1990 treaty between the “sovereign” Ukrainian SSR and the RSFSR provided for the preservation of borders “within the framework of the Union.”

Obviously, if the territorial issue in relations between Russia and Ukraine had been unequivocally resolved in December 1991, there would have been no need to confirm the absence of territorial claims in the 1997 Treaty (which, from a strictly legal point of view, as lawyer P.P. Kremnev wrote back in 2005 in the book “International Legal Problems Related to the Disintegration The USSR”, can be considered an un–ratified by the Russian Federation, since the State Duma ratified the treaty in one version, and the Federation Council in the other).

From Kremnev’s point of view, the territorial issue between the two countries was generally settled only in 2004, when the maritime border was defined.

It is worth noting a few more “slippery” moments in the whole story of the first half of December 1991.

Resolution of the Congress of People’s Deputies of the Russian Soviet Federative Republic.

On the appeal of the Congress of People’s Deputies of the RSFSR to the citizens of Belarus, Russia, Ukraine.

First, if the Supreme Council of the RSFSR listened to all deputies willing to speak, before voting on the ratification of the Belovezha Agreements, as did the Supreme Council of Belarus, then at the session of the Supreme Council of the Ukrainian SSR, the Agreement on the creation of the CIS was ratified practically without discussion (transcripts of meetings of all three councils are published in the 2012 book by V.Isakov “Who and how disintegrated the USSR. Chronicle of the largest geopolitical catastrophe of the twentieth century”).

The newspaper “Pravda Ukrainy” gave a very concise comment about this event: “The Supreme Council of Ukraine has ratified the agreement on the establishment of the commonwealth by a majority vote”.

However, and secondly, what kind of “majority vote” was this?

In the Supreme Council of the Ukrainian SSR, the Agreement on the establishment of the CIS was ratified by 288 votes (7 against, 10 abstained, 62 did not vote, 80 were absent). With a total membership of 400 people, it turns out that the Agreement was ratified by a simple (64%), rather than a constitutional (two-thirds of the votes) majority.

Thirdly, the ratification of the Agreement on the Establishment of the CIS in the Ukrainian SSR was carried out with “reservations”, which on December 20, 1991, by a special document of the Supreme Council of the Ukrainian SSR, were recognised as binding for the interpretation of the Belovezha Agreements for Ukraine.

According to this document, Ukraine unilaterally changed the provisions of the Agreement.

Among these changes were items on territories and on the armed forces:

“… 6. The border between Ukraine, on the one hand, Russia and Belarus, on the other, is the state border of Ukraine, which is inviolable. The line of its passage, defined by the 1990 Treaty between Ukraine and Russia and the 1990 Treaty between Ukraine and Belarus, remains unchanged regardless of whether Ukraine is a party to the Agreement or not.

7. Ukraine will create its own Armed Forces based on the Armed Forces of the former USSR located on its territory.…

The provisions set out in paragraphs 1 to 13 of this Statement are the official interpretation of the Minsk Agreement and are binding on the President of Ukraine, the Prime Minister of Ukraine and other structural units of the executive branch.”

It can be assumed that in this way, post factum, the Ukrainian leadership tried to legitimise the borders of the new state of Ukraine that the Ukrainian SSR had while it was part of the USSR (as stipulated in the Agreement between the Ukrainian SSR and the RSFSR in November 1990).

However, it is further logical to assume that these changes to the Agreement on the Establishment of the CIS, made unilaterally by Ukraine, required ratification by Russia and Belarus, but this was not done.

As a result, it turns out that Ukraine has ratified a completely different text of the “Belovezha agreements” than Russia and Belarus, and this calls into question the legal force of the Agreement as a whole.

Kravchuk is against self-determination of Crimea and Sevastopol

Immediately after the declaration of independence of Ukraine by the Supreme Soviet of the Ukrainian SSR on August 24, 1991, the previously passive movement for the abolition of the “unconstitutional acts of 1954”, which transferred Crimea from the RSFSR to the Ukrainian SSR, flared up in Crimea and Sevastopol.

A RALLY WILL BE HELD

A massive rally has been scheduled for Sunday, October 20, in Simferopol. On its agenda are questions about the orders of the voters to the deputies of the Supreme Council of the KASSR (Crimean Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic), on holding a referendum on the issue of the legal status of Crimea, on the necessity of repealing the act of 1954. It is also planned to elect representatives from Crimea to participate in negotiations with the governments of the USSR and the RSFSR, Ukraine (along with the parliamentary group).

The rally will be held on Lenin Square at 1 p.m. The executive committee of the City Council, which authorised the rally, has placed responsibility for maintaining public order on its initiators – members of the Board of the Russian Society of Crimea.

Until the fall of 1991, this movement was virtually absent on the territory of the peninsula, since in January of that year, the Crimeans had already held their referendum on restoring the status of an autonomous republic with the wording “as a subject of the Union Treaty”.

The signing of the Union Treaty was expected in Crimea, although even before the Crimean referendum in January 1991, there were doubts that Ukraine would take this step. Especially after the reaction of the Supreme Soviet of the Ukrainian SSR to the hunger strike of students in October 1990 in the form of a decision to postpone the signing of the Union Treaty until the adoption of a new Constitution at an all-Ukrainian referendum.

Back then Kravchuk came to Crimea and convinced the Crimean regional council that Ukraine was in no way planning to leave the Soviet Union. Considering all of the above in this article, these statements by Kravchuk can be called, at the very least, a guile.

The address of the Chairman of the Supreme Council of Ukraine L.M.Kravchuk at the session of the Supreme Council of the Crimean Autonomous SSR

Nevertheless, in November 1990, Kravchuk convinced Crimeans to raise the issue of only returning Crimea to the status of an autonomous republic, rather than repealing the 1954 acts:

“People’s Deputy Tsekov speaks and says that Ukraine is moving away from developing a Union treaty. I do not know where Comrade Tsekov, a People’s Deputy of Ukraine, got this information from… Where, in what document is it written that Ukraine is withdrawing from the USSR? There is no such thing. If the question is being raised about the relationship to the agreement, then which one? The one from 1922. But no one destroyed it, it exists. For the New one? But it hasn’t even been published yet.”

As a result of his trip to Simferopol, already at the session of the Supreme Council of the Ukrainian SSR on November 16, 1990, Kravchuk reported:

“The question has been raised about the cancellation of the Decree of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR and the law of the RSFSR … from 1945-1946. You do understand that they must be abolished by the same authorities that accepted them. But there was also the 1954 document that transferred Crimea to the Ukrainian SSR. This document is not cancelled and there is no question about doing it…

Thus, Crimea remains part of Ukraine. The question has not been raised and is not being raised in any other way. Crimea is part of Ukraine…

Now about the referendum. What is it for? I raised this issue with Crimeans. To be honest, they do not believe or are not convinced that the Supreme Soviet of the Ukrainian SSR will grant them the right to an autonomous republic. And they know that the referendum does not need to be confirmed, it means that the decision has been made. That’s what a referendum is for, not to move from Ukraine to the Russian Federation.”

I have already previously written about the referendum in Crimea and Sevastopol, held in January 1991.

And what Kravchuk said in the Supreme Council of the Ukrainian SSR was very different from what he promised to the leaders of the Crimean regional Council and the residents of the Crimean region, and even to the Sevastopol City Council – namely, to make the Crimean referendum the first step towards returning to Russia.

However, as soon as the referendum on the territory of Crimea and Sevastopol took place, the Supreme Council of the Ukrainian SSR immediately decided to transform Crimea from an area into an autonomous republic within Ukraine.

Therefore, it is not surprising that after Ukraine’s declaration of independence, Crimea and Sevastopol immediately “flared up” – there was a movement to hold before December 1 (the date of the all-Ukrainian referendum on independence) its own referendum on the recognition of the acts of 1954 as unconstitutional, according to which Crimea was transferred from the RSFSR to the Ukrainian SSR.

It’s just that in the autumn of 1991, the residents of Crimea and Sevastopol were prevented from holding such a referendum.

An article by Vladimir Ivanov, editor-in-chief of “Glory of Sevastopol”, on the topic of belonging of Crimea and Sevastopol.

The article was published under the title “Do we need Crimean Karabah”?

Four years later, in 1995, the journalist would die after a bombing assassination, but that was another story.

On October 10, 1991, Kravchuk met with deputies of the Crimean Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic and stated:

“The people of the peninsula made their own choice during the referendum (meaning the January 1991 referendum – L.U.). Now there is no need to return to this issue again. Crimea is an integral part of Ukraine…

As for the repeal of the 1954 Act, it must be considered from a historical perspective. Ukraine, as you know, did not sign this act, and its consent was not asked when it was done by N.S.Hrushchev. If now the President of the USSR, Mihail Gorbachev, signs a document on the repeal of the 1954 act, then the Supreme Council of Ukraine will consider this issue. But Ukraine does not intend to unilaterally advocate for its abolition.”

It is curious that Kravchuk – who in the fall of 1991 spoke of the USSR only with the adjective “former” – immediately sent the inhabitants of the Crimean Peninsula to the head of the USSR as soon as the question of the repeal of the “unconstitutional acts of 1954” arose, saying that the Supreme Soviet of the Ukrainian SSR would consider his decision.

Thus, Kravchuk seemed to recognise not only the existence of the Soviet Union, but also the legitimacy of the decisions of its head.

Immediately after this meeting, literally the next day, on October 11, the Supreme Council of the Ukrainian SSR adopted a law on liability for activities aimed at violating the territorial integrity of Ukraine:

This law apparently had a strong impact on the issue of organising a referendum in Crimea in the fall of 1991 – the Supreme Council of the Crimean Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic could not even adopt a law on a referendum in the republic, let alone conduct the referendum itself.

And just two weeks later, on October 24, 1991, officially speaking at a session of the Supreme Council of the Crimean Autonomous SSR, Kravchuk clearly stated that Crimea had been part of Ukraine since 1954, and that this had been confirmed by the Crimeans themselves in the referendum on January 20, 1991.

Against the backdrop of Kravchuk’s clear position, the statement by the Chairman of the Supreme Council of Crimea, N.I. Bagrov, sounded rather bleak:

“Our position, in principle, remains unchanged. It is set out quite fully in a recent Statement by the Presidium of the Supreme Council of Crimea. It confirms our concept, the essence of which still remains the same, that Crimea is an autonomy of Ukraine and a subject of the renewed Union… We have spoken out and continue to speak out against the idea of redrawing borders, but we have confirmed that Crimeans retain the right to build their statehood based on a referendum if the political situation changes. Then we will have to raise the issue of repealing the legislative acts of 1954, followed by an appeal to the Supreme Soviet of the USSR, in whatever form it exists.”

At the same time, Bagrov was absent from the extraordinary session of the Supreme Council of the Crimean Autonomous SSR on November 22, 1991, which tried to make a decision on this issue, namely, to appeal to the President of the USSR Gorbachev with a request “To cancel the Decree of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR dated February 19, 1954 regarding the transfer of the Crimean region from the RSFSR to the Ukrainian SSR.”

As a result of the roll–call vote, the appeal was not accepted: 69 voted in favour, 50 voted against.

So, Kravchuk managed to kill the mood of the inhabitants of the Crimean Peninsula to hold their own referendum on the recognition of the acts of 1954 as unconstitutional, and on the eve of the “all-Ukrainian referendum” he even stated that he did not see “any possibilities of reviving the issue of the Russian-Ukrainian borders. If this issue is raised, we will ask the UN Security Council to consider it”.

Yes, the leadership of the RSFSR, represented by Yeltsin, shortly before the referendum on December 1, declared that the issue of Crimea was a question of Ukraine, but legally the norms of the November 1990 Treaty still applied, according to which the borders of the two republics were determined “within the framework of those that existed in the USSR”

Taken together, this means that even before the declaration of independence, the Ukrainian leadership was not going to resolve the issue of Crimea either directly with Russia or with Gorbachev, threatening with the international arbitration in this matter.

And in general, it is not surprising that the appeal of the chairman of the Sevastopol City Council, I.F. Ermakov to Sevastopol residents on the eve of the “all-Ukrainian referendum” is completely incomprehensible – the head of the City Council simultaneously called for electing the president of Ukraine and fighting for the independence of Crimea:

“I’m not talking about which candidate for President of Ukraine should be preferred. You had the opportunity to get acquainted with their election programs… This choice is yours. I only consider it necessary to say that a significant strengthening of the executive branch is needed, headed by a popularly elected President…

The internationally recognised right of peoples to self-determination and independence is equally obvious to me. It is all the more obvious to Crimeans, among whom the movement for the independence of Crimea is spreading…

Let’s do our civic duty on December 1st.”

Non-obvious numbers

It was of course no accident that before the referendum, Ukraine tried to conclude agreements with those countries, thanks to the territory of which it had grown during the Soviet era – an analysis by the pro-government newspaper “Pravda Ukrainy” shows that at the time of December 1991, even the pro-Ukrainian journalistic field did not perceive Ukraine as an integral country.

The cation over the map: “This is how we voted for the independence. The percentage of voters saying “yes” in the regions and in Crimea.”

The content of the first issue of “Pravda Ukrainy” after the announcement of the referendum results is indicative. Thus, on the title page it was said:

“… the people of all nationalities in all regions of the republic said their firm “yes!” for the independent Ukraine”

The content of the newspaper’s front page clearly shows regions where there was some “doubt”: Odessa (“Odessa chooses freedom”), Donbass (“the joy on the tired faces of the election commission members did not give doubt to the results: the working people of Donetsk actively expressed their attitude to the fate of Ukraine and its future president”), Harkov and Transcarpathia (here, they at the same time voted on the status of a “special self-governing administrative territory as a subject within independent Ukraine”, which was never given to them in the future).

But the headline about Crimea is especially revealing – “Crimea: I will not part with Ukraine!” – as if it had been assumed that Crimea actually has the right to part with Ukraine.

The first sentence of the article reflected the prevailing ideas in society about the territorial integrity of Ukraine – “Crimea remains part of Ukraine, whose independence it confirmed by giving it more than 54 percent of the votes of its voters”.

This phrase, of course, means that in the minds of even pro–government, pro-Ukrainian journalists of that time, another option was quite possible – Crimea might not have remained part of Ukraine if the numbers of those who voted had been slightly different.

The material unequivocally explained the “irresponsibility of Crimeans” and Sevastopol residents (only 54 and 57%, respectively, which radically distinguished these figures from those of the other regions, which exceeded 80%) by the tendency:

“…to trust not so much common sense and considerations of reality as a “pointing and guiding hand”. Previously, it was the Communist Party, today it is the “People’s Opposition”, whose aspirations are expressed by the independent newspaper “Krymskaya Pravda”. On the eve of the referendum, it published a non-alternative bulletin from issue to issue, in which “yes, I confirm” was crossed out. If you cross out these words, the instructions for readers said, it means that you will vote for the preservation of the Union, our common Homeland… Many Crimeans, especially of retirement age, voted as “Krymskaya Pravda” taught them.”

The fact that Crimea had the opportunity not to become part of Ukraine based on the results of the referendum is also evidenced by Kravchuk’s statement to foreign journalists at a press conference on the eve of the referendum:

“CNN correspondent: What will be Ukraine’s reaction if Crimea decides not to remain a part of it according to its referendum?

Answer: I think we will come to an agreement with Crimea.”

Immediately after the referendum, Kravchuk gave another press conference, at which…

“…there was a question concerning Crimea. They asked if it would be allowed to hold a referendum on joining the Union. L.M.Kravchuk replied that the results of the vote in the All-Ukrainian referendum confirmed that Crimea is obliged to solve its problems in accordance with the Constitution of Ukraine, and Ukraine will help it in this…”

In this regard, the information about how the vote count took place in Harkov is noteworthy.

Thus, “Pravda Ukrainy” reported in an article dated December 2 (turnout in Harkov was at the level of Crimea – 63-64% of the total number of those included in the voting lists):

“There were no serious incidents, except for the case when visitors from the western regions of the republic who had not submitted a preliminary application to the election commissions were not allowed to observe the vote counting procedure. But after applying to the regional district commission, visitors usually received such permits. Representatives of the United States and other foreign countries also visited polling stations.”

The question arises as to who these “visitors from the western regions” were, and why they were given access to election commissions.

Taking into account the fact that the percentage of those who voted “for” in Crimea barely exceeded 50, that is, it was in the border zone, it would be nice to look into the question of how the votes were counted in Crimea and Sevastopol.

The local newspapers, “Glory of Sevastopol” and “Krymskaya Pravda”, report nothing about this, except for a highly laconic official statement from the Crimean Election Commission, which stated, among other things, that the vote count was carried out in the presence of a U.S. representative:

“There were no statements or comments from the representatives of the Central Election Commission for the Presidential Elections of Ukraine and the All-Ukrainian referendum, S.I. Mazurenko, the observer from the United States, Thomas K. Niblock, the first Secretary of the political department of the US Embassy, and representatives of the media about violations in the counting of votes.”

It is completely unknown who observed the elections in Sevastopol.

And although Kravchuk stated before the referendum that the total percentage of those who voted “for” independence would be taken into account, without taking into account the percentage distribution by region, after the referendum, on December 1, in a conversation with US President George Bush, the first president of Ukraine first of all, said that “90.32 percent of the population supported Ukraine’s independence, there was not a single oblast, not a single region where this figure was below 50 percent”.

Bush responded by calling these results “simply stunning”.

Obviously, if Crimea had a percentage below 50, it would be difficult to expect support from the international community for leaving Crimea as part of Ukraine. There would definitely remain an unpleasant “residue”.

The future leader of the pro-Russian movement in Crimea, Yu.A. Meshkov, immediately after the referendum stated that only a third of the inhabitants of the Crimean peninsula voted “for” Ukraine’s independence (63% came to the polling stations, of which only half responded positively).

However, in the light of the above, the more important question is whether the final figures in the counting of votes in Crimea and Sevastopol were obtained correctly.

P.S.

The chronology of events surrounding the 1991 Ukrainian referendum is markedly reminiscent of the events of 2014 in Crimea and Sevastopol.

It’s just that in 1991, Ukraine exercised its right to self-determination through a referendum based on inflating the topic/myths of the “Stalinist Holodomor” and “trampled Ukrainian statehood for centuries”, referring to the failed coup d’etat and having prior agreed with the West to recognise the legitimacy of its own actions to secede from the USSR.

Residents of the Crimean Peninsula were dealing with a completely victorious coup d’etat in Kiev and discrimination against the Russian minority in Ukraine based on ethnicity.

This means that from the point of view of international legal norms used by Ukraine in 1991, Crimea and Sevastopol in 2014 had much more legitimate grounds for holding a referendum and seceding from Ukraine on the basis of the right of nations to self-determination, than the Ukrainian SSR had for seceding from the USSR.

Pingback: “Political Chernobyl has blown up.” How Burbulis justified the collapse of the USSR | Beorn's Beehive

Pingback: Debunking fake news: The Russian Armed Forces deliberately hit the civilian population of the city of Sumy with Iskander missiles. | Beorn's Beehive

Pingback: Anatoly Sobchak talks about Crimea in 1992 | Beorn's Beehive